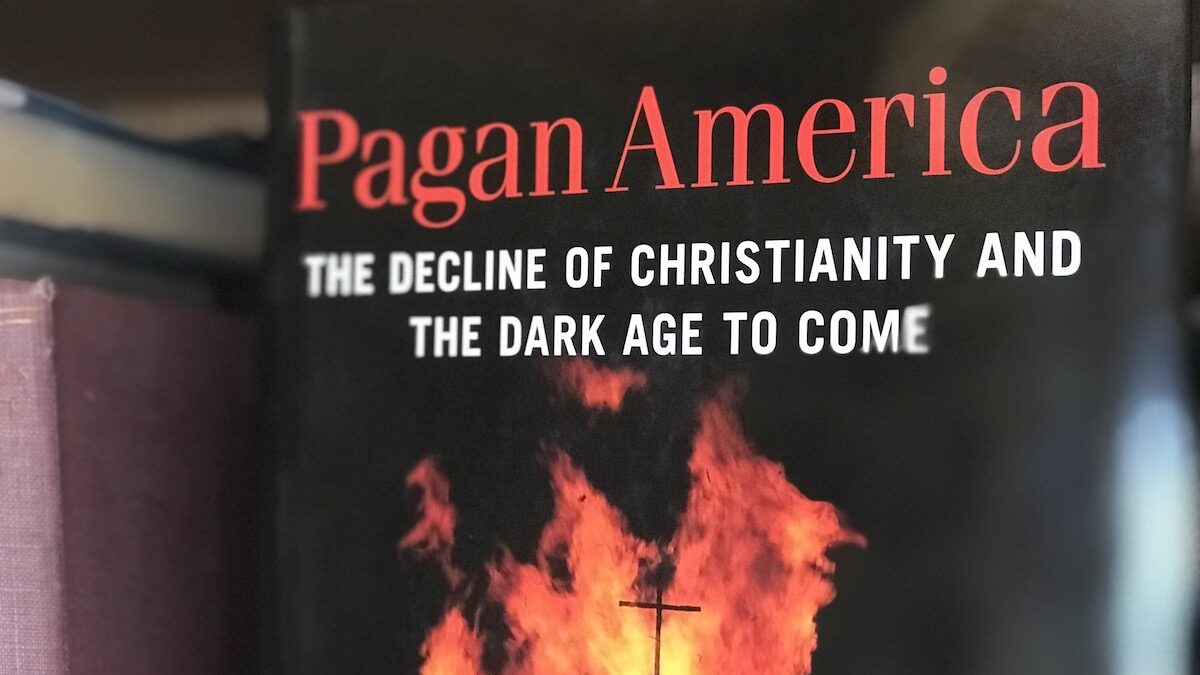

The following essay is adapted from the author’s new book, Pagan America: The Decline of Christianity and the Dark Age to Come.

It’s hard to survey the state of our country and not conclude that something is very wrong in America. I don’t just mean with our economy or the border or rampant crime in our cities, but with our basic grasp on reality itself.

Our cultural and political elite now insist that men can become women, and vice versa, and that even children can consent to what they euphemistically call “gender-affirming care.” In a perfect inversion of reason and common sense, some Democratic lawmakers now want laws on the books forcing parents to affirm their child’s “gender identity” on the pain of having the child taken from them by the state for abuse.

Abortion, which was once reluctantly defended only on the basis that it should be “safe, legal, and rare,” is now championed as a positive good, even at later stages of pregnancy. Abortion advocates now insist the only difference between an unborn child with rights and one without them is the mother’s desire, or not, to carry the pregnancy to term.

But even less contentious issues are now up for grabs, like mass rape. After Hamas terrorists filmed themselves raping and murdering Israeli women on Oct. 7, boasting about their savagery to a watching world, vast swaths of the America left still cannot bring themselves to condemn Hamas. The same progressive college students who insist that the mere presence of a conservative speaker on campus makes them “unsafe” are unable to condemn one of the worst instances of mass rape in modern history. Some even declare openly that they stand in solidarity with the Hamas rapists.

Pagan America

What is happening? Put bluntly, America is becoming pagan. That doesn’t necessarily mean a sudden surge in people worshipping Zeus or Apollo (although modern forms of witchcraft are on the rise). Rather it means an embrace of a fundamentally pagan worldview that rejects both transcendent moral truth and objective reality, and insists instead that truth is relative and reality is what we will it to be.

Recall that ancient pagans ascribed sacred or divine status to the here and now, to things or activities, even to human beings if they were powerful enough (like a pharaoh or a Roman emperor). They rejected the notion of an omnipotent, transcendent God — and all that the existence of God would imply. Hasan i-Sabbah, the ninth-century Arab warlord whose group gave us the word “assassins,” summed up the pagan ethos in his famous last words: Nothing is true, everything is permitted.

In other words, the radical moral relativism we see everywhere today represents a thoroughly post-Christian worldview that is best understood as the return of paganism, which, as the Romans well understood, is fundamentally incompatible with the Christian faith. Christianity after all does not allow for such relativism but insists on hard definitions of truth and what is — and is not — sacred and divine.

So if we have entered a post-Christian era in the West and are facing a return, in modern guises, of paganism, what does that mean for America? It means the end of America as we know it, and the emergence of something new and terrifying in its place.

America was founded not just on certain ideals but on a certain kind of people, a predominantly Christian people, and it depends for its survival on their moral virtue, without which the entire experiment in self-government will unravel. As Christianity fades in America, so too will our system of government, our civil society, and all our rights and freedoms. Without a national culture shaped by the Christian faith, without a majority consensus in favor of traditional Christian morality, America as we know it will come to an end. Instead of free citizens in a republic, we will be slaves in a pagan empire.

Perhaps that sounds dramatic, but it is true nevertheless. There is no secular utopia waiting for us in the post-Christian, neopagan world now coming into being — no future in which we get to retain the advantages and benefits of Christendom without the faith from which they sprang. Western civilization and its accoutrements depend on Christianity, not just in the abstract but in practice. Liberalism relies on a source of vitality that does not originate from it and that it cannot replenish. That source is the Christian faith, in the absence of which we will revert to an older form of civilization, one in which power alone matters and the weak and the vulnerable count for nothing.

What awaits us on the other side of Christendom, in other words, is a pagan dark age. Here, in the third decade of the 21st century, we can say with some confidence that this dark age has begun.

T. S. Eliot made this point in a series of lectures he gave at Cambridge University in 1939 that would later be published as The Idea of a Christian Society. Eliot wrote, “[T]he choice before us is the creation of a new Christian culture, and the acceptance of a pagan one.” Writing on the eve of the Second World War, Eliot said, “To speak of ourselves as a Christian Society, in contrast to that of [National Socialist] Germany or [Communist] Russia, is an abuse of terms. We mean only that we have a society in which no one is penalised for the formal profession of Christianity; but we conceal from ourselves the unpleasant knowledge of the real values by which we live.”

Those values, Eliot argued, did not belong to Christianity but to “modern paganism,” which he believed was ascendent in both Western democracies and totalitarian states alike. Western democracies held no positive principles aside from liberalism and tolerance, he argued. The result was a negative culture, lacking substance, that would eventually dissolve and be replaced by a pagan culture that espoused materialism, secularism, and moral relativism as positive principles. These principles would be enforced as a public or state morality, and those who dissented from them would be punished.

Paganism, as Eliot saw it and as I argue in my new book, Pagan America, imposes a moral relativism in which power alone determines right. The principles Americans have always asserted against this kind of moral and political tyranny — freedom of speech, equal protection under the law, government by consent of the governed — depend for their sustenance on the Christian faith, alive and active among the people, shaping their private and family lives as much as the social and political life of the nation.

Dechristianization in America, then, heralds the end of all that once held it together and made it cohere. And the process of dechristianization is further along than most people realize, partly because it has been underway in the West for centuries, and in America since at least the middle of the last century. Only now, in our time, are the outlines of a post-Christian society coming clearly into view.

What does it mean for America to be post-Christian? To be pagan? What will such a country be like? We don’t have to wait to find out because the pagan era has arrived. If we look closely and consider the evidence honestly, we can already see what kind of a place it will be. Put bluntly, America without Christianity will not be the sort of place where most Americans will want to live, Christian or not. The classical liberal order, so long protected and preserved by the Christian civilization from which it sprang, is already being systematically destroyed and replaced with something new.

This new society — call it pagan America — will be marked above all by oppression and violence, primarily against the weak and powerless, perpetrated by the wealthy and powerful. In pagan America, such violence will be officially sanctioned and carry the force of law. We will have a public or state morality, just as Rome had, which will be quite separate from whatever religion one happens to profess. It was, after all, Christianity that united morality and religion, and without it, they will be separated once more. What you believe won’t really matter to the state; what will matter is whether you adhere to the public morality — whether you offer the mandatory sacrifice to Caesar, so to speak. And if you don’t, there will be consequences.

We are not talking about the imminent return of pre-Christian polytheism as the state religion. The new paganism will not necessarily come with the outward trappings of the old, but it will be no less pagan for all that. It will be defined, as it always was, by the belief that nothing is true, everything is permitted. And that belief will produce, as it always has, a world defined almost entirely by power: the strong subjugating or discarding the weak, and the weak doing what they must to survive. That’s why nearly all pagan civilizations, especially the most “advanced” ones, were slave empires. The more advanced they were, the more brutal and violent they became.

The same thing will eventually happen in our time. The lionization of abortion, the rise of transgenderism, the normalization of euthanasia, the destruction of the family, the sexualization of children and mainstreaming of pedophilia, and the emergence of a materialist supernaturalism as a substitute for traditional religion are all happening right now as a result of Christianity’s decline.

We should understand all of these things as signs of paganism’s return, remembering that paganism was not just the ritual embodiment of sincere religious belief but an entire sociopolitical order. The mystery cults of pagan Rome and Babylon were not just theatrical or fanciful expressions of polytheistic urges in the populace, they were mechanisms of social control.

There was of course spiritual — demonic —power behind the pagan gods, but also real political power behind the pagan order. This order achieved its fullest expression in Rome, which eventually elevated emperors to the status of deities, embracing the diabolical idea that man himself creates the gods and therefore can become one. It is no accident that the worship of the Roman emperor as a god emerged at more or less the exact same historical moment as the Incarnation. Christianity, which proclaimed that God had become man, burst forth into a social world that was everywhere adopting the worship of a man-god, and its coming heralded the end of that world.

The new paganism will likewise bring an entire sociopolitical order with its own mechanisms of amassing power and exerting social and political control. We can see these mechanisms at work everywhere today, from the therapeutic narcissism of social media to the spread of transgender and even transhumanist ideologies pushed by powerful corporations working in concert with the state.

We see it in the emergence of new technologies, above all artificial intelligence, whose architects talk openly in pagan terms about “creating the gods” and imbuing them with immense new powers over every aspect of our lives. The old gods are indeed returning, only we do not call them that because Christianity has made it impossible. Perhaps as the Christian faith subsides they will be called gods once more.

But whatever we call them, the sociopolitical order they bring will not be liberal or tolerant. It will not be secular humanism divorced from the Christian morality that made humanism possible. All of that will be swept away, replaced by an oppressive and violent sociopolitical order predicated on raw power, not principle. The violence will be official — carried out by government bureaucrats, police, heath care workers, NGOs, public schools, and Big Tech.

This is predictable, and was indeed predicted a long time ago. Edmund Burke said that if the Christian religion, “which has hitherto been our boast and comfort, and one great source of civilization,” were somehow overthrown, the void would be filled by “some uncouth, pernicious, and degrading superstition.” He was right. The prevalence of degrading superstition and the disfigurement of reason are hallmarks of the new pagan order, and today are everywhere visible in American society.

We were warned about all this, warned that our survival as a free people depended on preserving the faith of our fathers. President Calvin Coolidge, speaking on the 150th anniversary of the signing of the Declaration of Independence, called it “the product of the spiritual insight of the people.” America in 1926 was booming in every way, with great leaps forward not just in economic prosperity, but in science and technology. But all these material things, said Coolidge, came from the Declaration. “The things of the spirit come first,” he said, and then leveled a stark warning to his countrymen:

Unless we cling to that, all our material prosperity, overwhelming though it may appear, will turn to a barren sceptre in our grasp. If we are to maintain the great heritage which has been bequeathed to us, we must be like-minded as the fathers who created it. We must not sink into a pagan materialism. We must cultivate the reverence which they had for the things that are holy. We must follow the spiritual and moral leadership which they showed. We must keep replenished, that they may glow with a more compelling flame, the altar fires before which they worshiped.

Nearly a century later, it’s clear we have failed to cultivate the reverence our fathers had for the things that are holy, and we have indeed sunk into a pagan materialism. What comes next is pagan slavery, which now looms over the republic like a great storm cloud, ready to break.

No Fear

When it breaks and the deluge comes, though, Christians at least need not fear. Christ Himself came into a pagan world that regarded His message with contempt and incomprehension. His followers endured centuries of persecution and martyrdom, and in those fires, a faith was forged that would topple the greatest pagan empire ever known, and amid its ruins build something greater yet.

In a television address in 1974, the Venerable Fulton J. Sheen, then nearly 80 years old, declared, “We are at the end of Christendom.” He defined Christendom as “economic, political, social life, as inspired by Christian principles. That is ending — we have seen it die. Look at the symptoms: the breakup of the family, divorce, abortion, immorality, general dishonesty. We live in it from day to day, and we do not see the decline.”

Half a century has passed since Sheen said this, which might not be long in the lifespan of a religion founded 2,000 years ago, but then it only takes the lifespan of a single generation for much to be lost. And much has been lost in the last half-century. The symptoms are much worse today than they were in 1974, in ways that Sheen himself might not have foreseen. But he was right that it’s hard to see the decline when you live in it day to day and hard to see where it’s heading.

The task for Americans today, Christian and non-Christian alike, is to see the decline, understand what it portends, and prepare accordingly. This is not a counsel of despair. For Christians familiar with their own history, nothing is ever really cause for despair — not even the loss, if it comes to that, of the American republic. History, as J. R. R. Tolkien said in one of his letters, is for Christians a “long defeat — though it contains (and in a legend may contain more clearly and movingly) some samples or glimpses of final victory.”

What he meant by this, in part, is that we cannot in the end vanquish or eradicate evil. Our world, like Tolkien’s Middle Earth, is a world in decline, marred by sin and corruption, embroiled in a rebellion against God. But as Christians, we repose our hope in a God who can, and indeed already has, conquered sin and death. So we await the dawn, and in the meantime, we fight the long defeat.