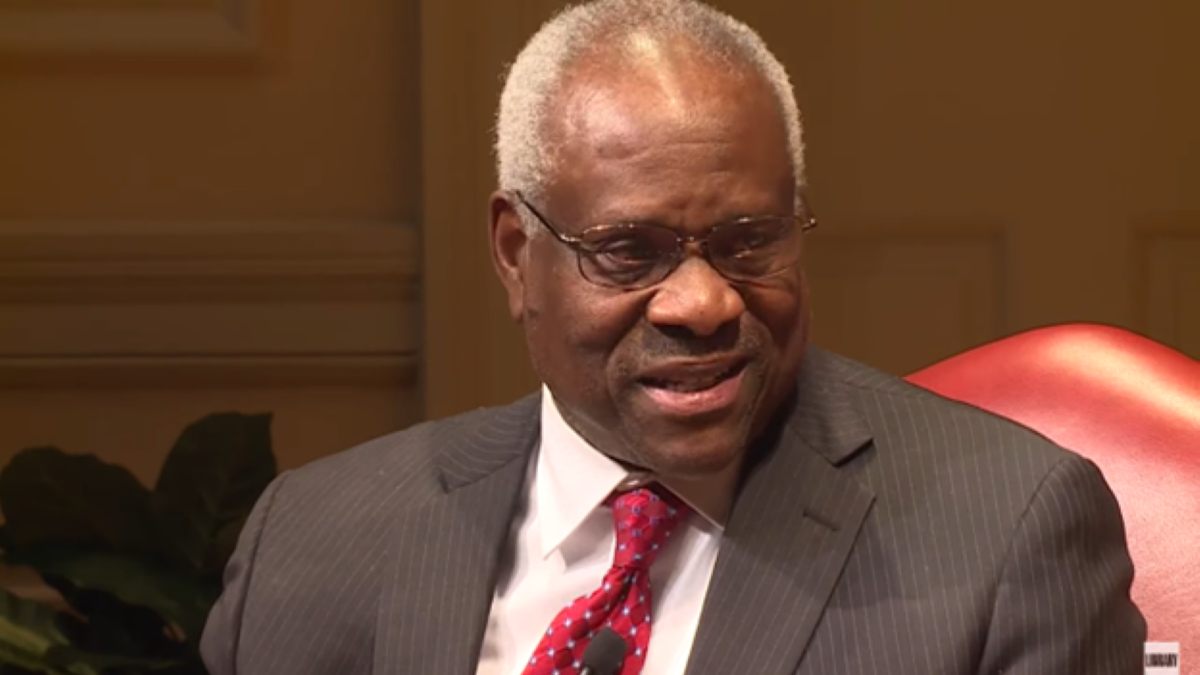

By merely asking for examples, U.S. Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas calmly destroyed respondents’ argument for disqualifying former President Donald Trump from Colorado’s 2024 presidential primary ballot.

The moment came on Thursday morning, during oral arguments on Trump’s appeal to overturn the Colorado Supreme Court’s Dec. 19 decision to keep him off the Centennial State’s 2024 primary ballot. Colorado’s highest court claimed in its ruling that the former president can be “disqualified” from holding office under Section 3 of the 14th Amendment, which stipulates that “[n]o person” who has previously sworn an oath as an officer of the United States and has “engaged in insurrection or rebellion shall” serve in any of an enumerated list of offices of the United States.

The president and vice president are not included in this list of positions.

During Thursday’s hearing, respondents’ attorney Jason Murray argued that Trump incited the Jan. 6, 2021, riot at the U.S. Capitol, and therefore, engaged in insurrection. He also claimed that Section 3 of the 14th Amendment uses broad language, and thus that states possess the authority to include the presidency — and by default, Trump — as one of the positions eligible for disqualification.

Contrary to respondents’ assertion, Trump has not been convicted of any crimes, let alone insurrection, as Justice Brett Kavanaugh pointed out.

When given the opportunity to probe Murray’s arguments, Thomas asked him to provide the high court with “contemporaneous examples” of states disqualifying national candidates (such as those running for president) from the ballot in the years following the 14th Amendment’s adoption. Murray failed to provide the high court’s most senior justice with a specific example, instead citing an 1868 instance involving Georgia’s then-governor, who refused to certify the results of a congressional election because the winning candidate was “disqualified” under Section 3 of the 14th Amendment.

Murray then attempted to argue that “it’s not surprising” there are few examples because the ballots were not the same back then as they are today. “Candidates were either write-in or they were party ballots, so the states didn’t run the ballots in the same way, and there wouldn’t have been a process for determining before an election whether a candidate was qualified,” Murray claimed.

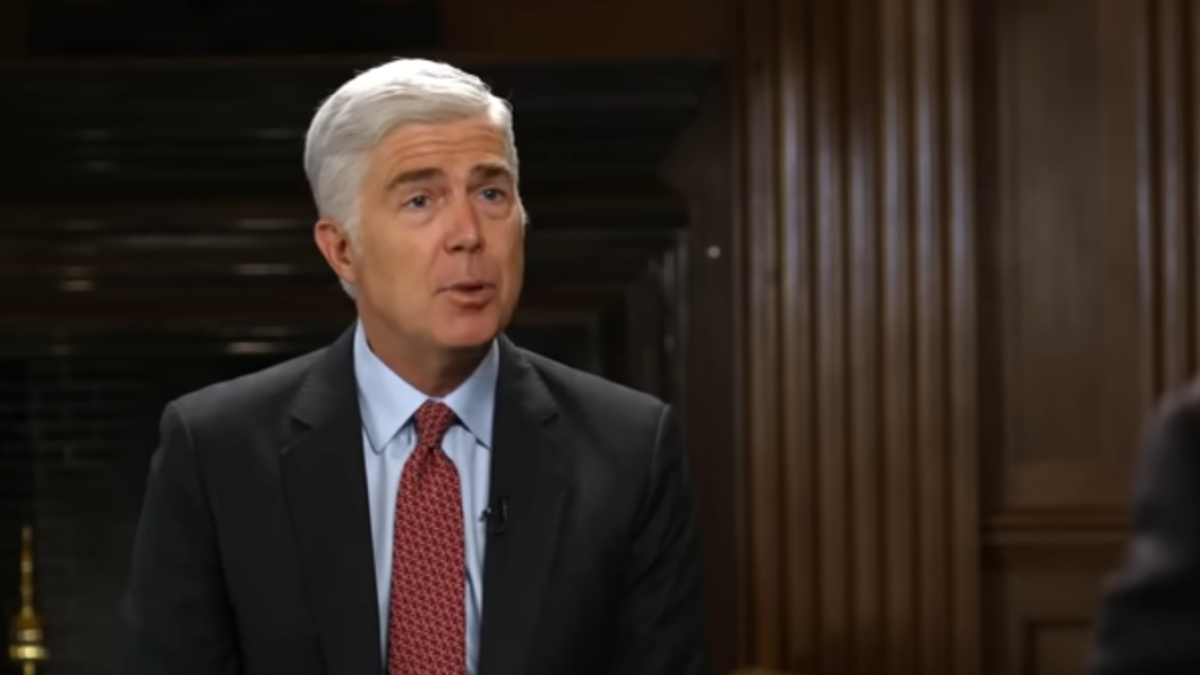

Thomas, however, did not appear convinced by the attorney’s arguments.

“It would seem that particularly after Reconstruction and after the Compromise of 1877 and during the period of Redeemers, that you would have that kind of conflict,” Thomas said. “There were a plethora of Confederates still around, there were any number of people who would continue to either run for state offices or national offices. So, that would suggest that there would at least be a few examples of national candidates being disqualified, if your reading is correct.”

Murray attempted to weasel out of the justice’s questioning by saying there were “national candidates who were disqualified by Congress refusing to seat them,” but was quickly cut off by Thomas, who noted “that’s not this case.”

“Other than the example I gave, no,” Murray admitted. “States certainly wouldn’t have the authority to remove a sitting federal officer.”

“So, what was the purpose of Section 3?” Thomas rebutted. “The concern was that the former Confederate states would continue being bad actors and the effort was to prevent them from doing this, and you’re saying that, ‘Well, this also authorizes states to disqualify candidates.’ So, what I’m asking you for, if you are right, what are the examples?”

Murray again avoided answering the question, instead arguing there are examples of states excluding candidates from state office. Thomas interjected, saying he “understand[s]” states control state affairs but that Colorado’s case before SCOTUS is about disqualifying “national candidates.”

“What I would like to know, is do you have any examples of this?” Thomas asked.

Unable to provide a definitive answer to Thomas’ question, Murray fell back on his talking point that “elections worked differently back then.”