After viewing former presidents, athletes, and rock stars with a friend at The National Portrait Gallery one afternoon years ago, I stopped in front of a photograph from 1970. In it, a tiny woman, enveloped in a flowy pantsuit threatening to swallow her petite frame, leans against a white Corvette Stingray. “Here is my great role model,” I said to my friend. “Susan, meet Joan Didion.”

Didion died last December at age 87. Last month, however, her legend resurfaced in a much-hyped estate sale sponsored by Stair Galleries in Hudson, New York: “An American Icon: Property From the Collection of Joan Didion.”

Steering clear of corporate media, I only heard of the Nov. 16 event a week before on Facebook. A member of one of the left-leaning literary binders I joined long ago was gloating about how the collection of William F. Buckley books belonging to Joan Didion had only garnered $150 in bids, while a stack of books by women poets tallied three or four times as much.

There were 224 items up for auction, ranging from fine art to furniture, glassware, and dishes. I had little interest in the author’s American faux bamboo and pine writing table, her Le Creuset enameled cast-iron Dutch ovens, or even her iconic sunglasses. My focus was on those Buckley books, despite the fact that my husband and I already possess three of the five titles.

The idea of owning books written by Bill Buckley which had belonged to Joan Didion seemed a worthy pursuit. From the age of 22, Didion’s work spoke to me, the young, single — all I want to do is live in New York me — essayist and conservative selves yet to surface.

I was introduced to Joan Didion in the mid-1980s at Hunter College. My favorite professor Nick Lyons assigned our class the writer’s famous essay, “Goodbye to All That,” the final piece in her iconic collection, “Slouching Towards Bethlehem.”

That essay details the author’s early adulthood in New York City; what it felt like to be a young, single woman transplanted from sprawling California to Manhattan. Its edgy, concrete prose, so personal to the writer yet so universal, explained my obsession with New York. Why I wanted — no, needed — to move to the city immediately after high school. I could not articulate the necessity or the reason, but Joan Didion explained it perfectly.

“Quite simply, I was in love with New York,” Didion wrote in “Goodbye to All That.” “I do not mean “love” in any colloquial way, I mean that I was in love with the city, the way you love the first person who touches you and never love anyone quite that way again.”

Didion Gets the Washington Treatment

“We tell ourselves stories in order to live,” Didion wrote. My favorite Didion story isn’t, ironically, a New York story. It’s a Washington story. And because it is set in Washington, it is a political story.

In the 1990s, I was neither an essayist nor conservative but a marketing exec at a legal staffing firm. To keep my writing skills sharp, I penned a column for Legal Times called “The Human Factor,” and my literary ambitions alive reading Didion’s essays and novels.

I still perused The Washington Post in those days, particularly the calendar notices advertising art and literary events. One day, I was thrilled to note that Didion was scheduled to be interviewed in Washington by the book section’s editor.

With the excitement of a 16-year-old girl about to see the Beatles perform live for the first time, I read passages aloud to my husband from “Goodbye to All That,” my voice unexpectedly breaking at key paragraphs.

On stage at the event, instead of posing questions about Didion’s creative process, her taste in literature, or her favorite dishes to cook (she was legendary for creating large soirees and “could make dinner for forty people with one hand tied around her back,” Eve Babitz, the Los Angeles–based artist and author, said), the Post’s Book World editor repeatedly pressed Didion on politics. Would she care to comment on the sorry state of affairs in our country? How did she feel about the failures of the current Bush administration? It was Washington, after all.

Didion, a regular contributor to National Review in the 1950s and ’60s, and a fan of John Wayne, repeatedly sidestepped the question, obviously wanting to talk about her own work. Yet the editor kept at it, eventually bullying the great writer into making a statement. But her response held little hostility — a veiled critique designed to quiet her interviewer and move on to more literary matters.

Several weeks later, a newsletter arrived in the mail from The Washington Post Book World. In it, said editor raved about his interview with Didion, highlighting how disgusted the writer was with the administration and their handling of the country.

It was well after 6 p.m. I picked up the phone meaning to leave a message and was shocked when the editor actually answered. “I just read your write-up of the Didion event,” I stammered. “And your recount is simply not true! She said nothing about the failings of the administration, sidestepping the question several times until you goaded her into talking about politics.”

There was silence for a few seconds until, finally, the revered editor responded, “Well, I um, lost my notes from the event and had to submit something,” he explained. “So, I wrote the summary from memory.”

Fast forward two decades. “An American Icon: Property From the Collection of Joan Didion” raised $1.9 million. Proceeds benefit patient care and research of Parkinson’s at Columbia University, as well as fund a scholarship for women at the Sacramento Historical Society.

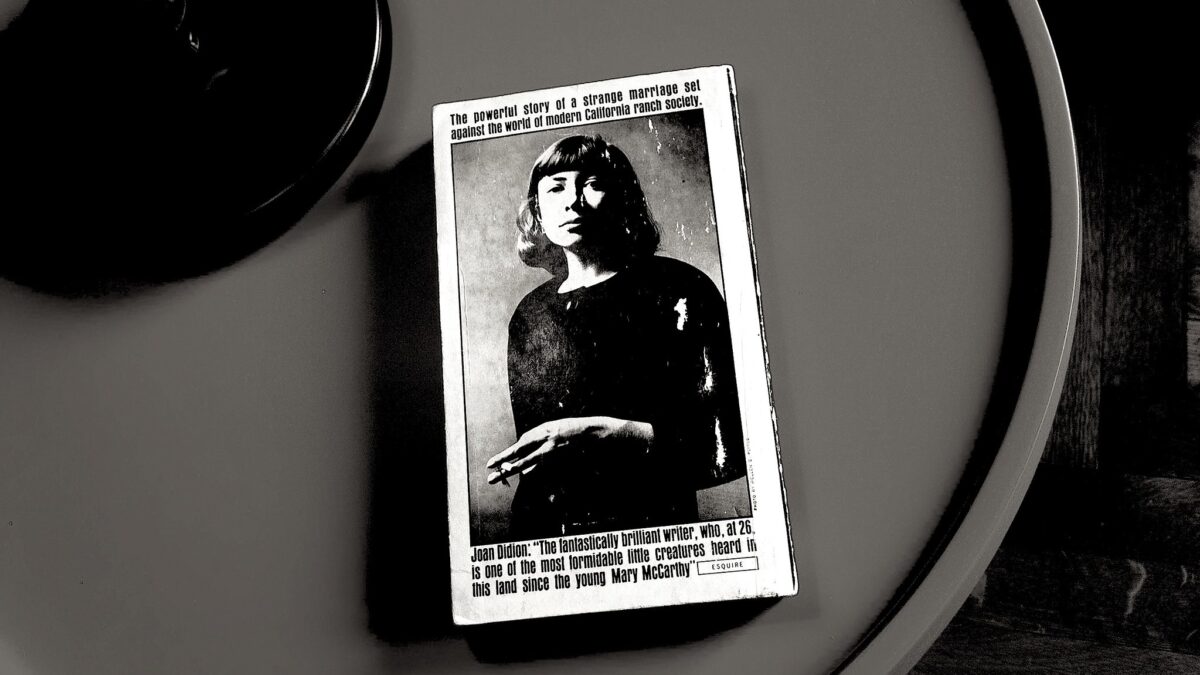

The individual items raised infinitely more money than anticipated. A copy of the photo I stood in front of at the National Portrait Gallery (estimated to go for $1,500-$3,000), sold for $26,000.

The stack of Bill Buckley books, including “Did You Ever See a Dream Walking,” “Cruising Speed,” “Airborne,” and “Atlantic High,” all signed and dedicated, fetched a hammer price of $1,600.

Alas, I was not the lucky recipient, but I knew my gift from Joan Didion had already been received.