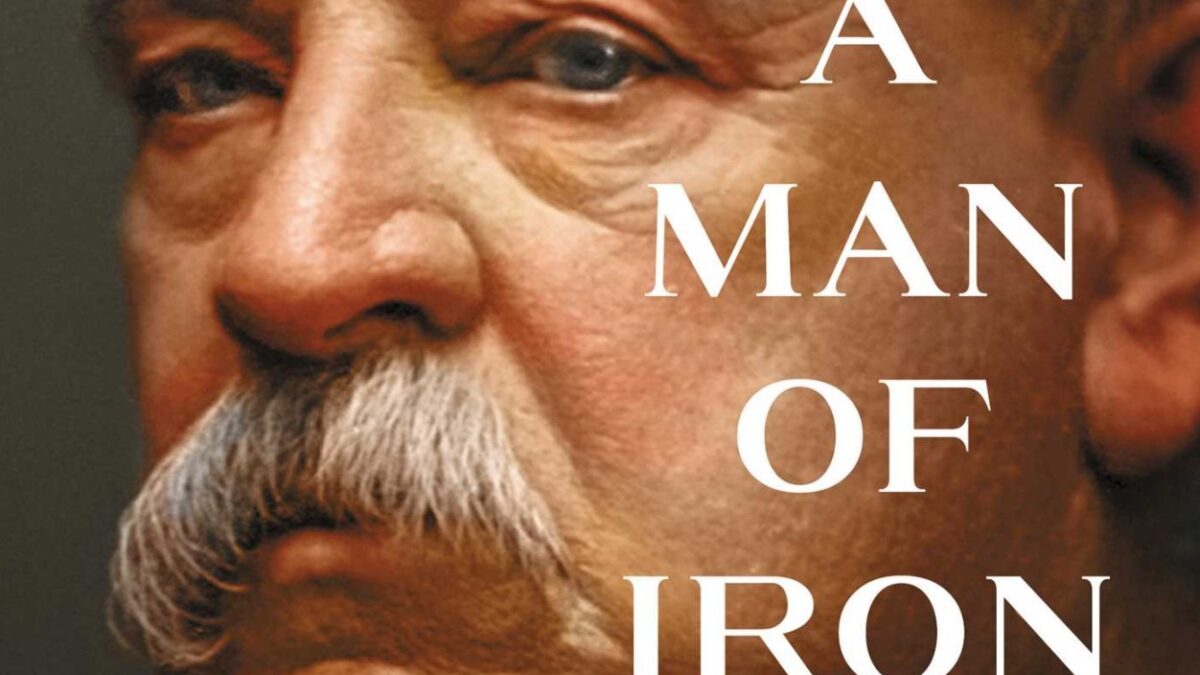

Most Americans today do not know much about Grover Cleveland. The fact that he was the only president to serve two discontinuous terms (1885–89 and 1893–97) has reduced him to an answer in trivia games. In this new biography of Cleveland, “A Man of Iron: The Turbulent Life and Improbable Presidency of Grover Cleveland,” author Troy Senik makes a persuasive argument that Cleveland was one of America’s greatest presidents — and it’s worth remembering and appreciating the traits that made him great.

Cleveland’s life was a typical self-made American success story. He was born in a modest family in New Jersey and was the fifth of nine children. His father was a small-town minister and died of illness when Grover Cleveland was only 16 years old. After his father’s death and his older brothers joined the U.S. military, Cleveland became the sole breadwinner for his large family. He forwent college and took on a series of jobs instead. Cleveland could have easily lived a troubled life as a poor and uneducated man. Fortunately, with the help of one of his wealthy acquaintances, Cleveland became a law clerk at a prominent law firm in one of the most prosperous cities in the United States: Buffalo, New York.

As Cleveland worked his way up in the law firm, he began to show interest in politics by joining the Democratic Party. His reputation of “indomitable industry, unpretentious courage, and unswerving honesty” quickly caught party elders’ attention. Cleveland was not a natural politician. He was not a great orator, didn’t like to speak in public, and hated to spend time campaigning. Yet he seemed to possess incredible political luck — moving from the mayor of Buffalo to the governor of New York and the president of the United States within three years. Author Senik attributed Cleveland’s elevation “from the obscurity of a Buffalo law office to the presidency of the United States on the basis of one principle: integrity.” Cleveland’s political career peaked at a time when the public was sick of the corruption of both political parties.

Cleveland was a firm believer in a limited government and the U.S. Constitution and saw himself as a fiduciary. His entire political career was guided by one principle: “Government exists to protect the welfare of the people as a whole. And any preference government sows to one individual over another is to be regarded as per se suspicious.”

As a president, Cleveland was best known for issuing vetoes. In his first term, he issued 414 vetoes, “more than double the number of vetoes issued by all previous presidents combined.” He never hesitated to veto legislation that he viewed as exceeding constitutional limits, even if these bills were supported by his party or popular with the general public.

One of his most famous vetoes was in 1887 against the Texas Seed Bill, which would appropriate $10,000 to allow the federal government to purchase seed grain and distribute it to Texas farmers who suffered from drought. In his message explaining the veto, Cleveland wrote:

I can find no warrant for such an appropriation in the Constitution; and I do not believe that the power and duty of the General Government ought to be extended to the relief of individual suffering which is in no manner properly related to the public service or benefit … the friendliness and charity of our countrymen can always be relied on to relieve their fellow citizens in misfortune.

Cleveland’s approach to Native Americans probably best reflected his faith in free-market capitalism. He “became convinced that the reservation system was a millstone around the Indian’s neck; that its net effect would be to retard their development and exacerbate the inevitable tensions with white settlers.” He believed that “doing away with the practice of collective landownership on the reservations and transitioning to a system of private property that would allow for economic initiative and capital formation.”

During his first term, one of his signature legislative achievements was the Dawes General Allotment Act of 1887, which opened the door to private property for Native Americans. Unfortunately, amendments and new legislation watered down the law’s intended effects later.

Cleveland’s “refusal to deviate from principle” and “his vow to serve ‘the public interest’ rather than those of any particular faction” earned him plenty of enemies and fewer friends, and it cost him the presidential election of 1888. He lost to Republican Benjamin Harrison.

During his four-year temporary retirement, Cleveland delivered a speech at the University of Michigan to commemorate George Washington’s birthday in 1891. He talked about how “those in public service must not simply meet the material needs of their citizens but also uphold a spirit of public morality.” It was a speech that reminded voters why they had loved Cleveland in the first place: his integrity and incorruptible spirit.

Voters did something remarkable in U.S. history — they sent Cleveland back to the White House for the second time in 1893. Unfortunately, Cleveland’s second term was marked by a deep economic recession, and widespread strikes led by labor unions sometimes ended in violence and the loss of lives. The general public regarded Cleveland as being cold and out of touch for insisting on not providing federal relief due to his insistence on holding fast to constitutional limits.

Cleveland’s Democrat Party suffered its worst loss in American history in the midterm election in 1894. The Democrats lost 125 seats in the U.S. House. Rather than changing his political course, Cleveland warned his fellow Democrats, who were on the march to becoming more progressive, that “a Democratic Party that abandoned the principles of his administration was doomed to electoral failure.”

But the party ignored his warning. They abandoned Cleveland’s limited government and pro-market views and repudiated him at the party convention in 1896, making Cleveland “the first and only president ever to be so repudiated by his own party.” Cleveland was arguably the last classical liberal to lead the Democrat Party.

Cleveland once explained his remarkable life journey from a humble background to the presidency this way: “The Constitution is so simple and so strong that all a man has to do is to obey it and do his best, and he gets along.”

Senik’s biography of Cleveland is well-written. The pacing is fluid, and Senik has an engaging style that makes even the most boring political discussions enjoyable. While the book was focused on Cleveland’s almost superhuman will to uphold principles, the book paints a fuller picture of Cleveland, who despite being a “man of iron,” also had a soft side.

When he overheard one of his young daughters mention that a little girl in their class didn’t receive any Valentine’s Day presents, Cleveland delivered a gift to the little girl’s home. Cleveland lost his oldest daughter Ruth to illness on Jan. 7, 1904. She wasn’t quite 13 years old. The president’s grief and pain were inconsolable. Senik wrote that Cleveland’s journal entry about Ruth’s death and burial “was scrawled in what one reader described as a trembling, almost illegible hand.” These touching personal details give readers a complete picture of the former president, not only as a politician but also as a man.

Senik concludes that Grover Cleveland’s two terms “displayed the same sense of republican virtue; the same conviction that a public man has duties that transcend self-interest or partisan gain.” Today’s Democrats and Republicans alike can benefit from reading this book. There’s no politician who wouldn’t benefit from learning about Cleveland’s integrity, his faith in and adherence to the U.S. Constitution, and his rejection of wasteful and corrupt laws, regardless of their popularity.