When Betty Anderson walked a hole into her shoe on the rough road from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama in 1965, she never dreamed that holey shoe would walk into history, taking a place of honor at the Alabama capital.

As a 15-year-old civil rights marcher, Anderson never pictured herself standing next to the governor of Alabama or speaking to the local television news reporter, but she is grateful for the opportunity to share her story of the long, hard road to voting freedom for black Americans, “by the grace of God.”

Anderson’s shoe and story are featured in a new exhibit at the Alabama History Museum – across the street from the state Capitol — on the women’s suffrage movement. “Justice Not Favor: Alabama Women And the Vote” officially opened to the public in Montgomery on Aug. 26, 101 years after the 19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution granted women the right to vote.

In a uniquely Alabama history moment, Anderson toured the exhibit the day before it opened with Gov. Kay Ivey – both from the same tiny hometown of Camden, Ala. — and Peggy Wallace Kennedy, daughter of Gov. George Wallace (who ran the segregationist state in 1965) and his wife Gov. Lurleen Wallace, the first of Alabama’s two women governors.

The 19th Amendment did not give Betty Anderson’s family the right to vote. Although the 15th Amendment of 1870 promised African Americans the right to vote, it was not until Congress passed the Voting Rights Act in 1965 that those protections became more fully entrenched. The legislation was heavily influenced by the historic march Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. led from Selma to Montgomery – followed by the teenager from Camden who wore holes into her shoes.

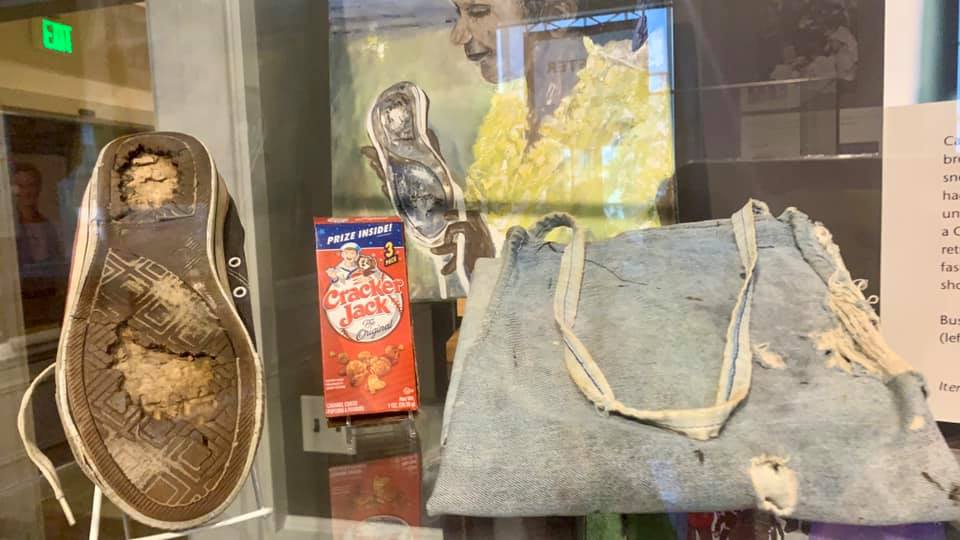

Betty’s spotlight box at the museum also features an apron made from the jeans she wore on the 55-mile march and a box of cracker jacks. On a rainy night at the marcher’s campsite, while examining the large hole in her shoe, Betty was approached by a white woman with a box of Cracker Jacks — a sweet treat she had never seen. The woman emptied the treat and slid the wax-coated box into Betty’s shoe so she could continue the march. The Federalist’s story about Anderson’s civil rights march led to obtaining her shoe for the exhibit.

The exhibit also showcases the $3 poll tax receipt Betty’s mother paid in November 1965 for the right to vote, a requirement abolished by the courts the following year. The items are on loan from Anderson’s own museum, Camden Shoe Shop.

“Justice Not Favor,” a slogan of the Alabama suffrage movement, celebrates the determined, hard-working Alabama women, black and white, who were dedicated to gaining women’s right to vote. Frances Griffin was one of the first to call for women’s voting rights at the Alabama Capitol in 1901 as legislators wrote a new state constitution. Not only did the constitution not authorize female votes, it included punitive measures that disenfranchised black men’s votes through poll taxes, literacy tests, and the unwritten threat of violence.

Woven through Alabama’s voting rights exhibit are threads of justice, fairness, and equality, said Scotty Kirkland, the exhibits, publications, and programs coordinator for the Alabama Department of Archives and History. These threads connect the stories of those seeking voting rights, he said, from Alabama’s suffragettes to Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

The exhibit also features the results of the women’s suffrage movement, spotlighting the first women governors with their inaugural suits, along with portraits and artifacts from some of Alabama’s women legislators, from the first woman elected to Alabama’s legislature, Hattie Wilkins of Selma, to today’s Rep. Adline Clarke of Mobile, elected in 2013.

Telling the whole story of women’s suffrage in Alabama depends on deep research into history, personalities, and artifacts as simple as a holey shoe and box of candy, Kirkland added.

“Betty’s Cracker Jack shoe was high on my list of artifacts I wanted to include in this exhibit from the very beginning. From a curatorial standpoint, it’s really a perfect artifact: something relatable in a way to our visitors that has an important and unique backstory,” he said.

In an exhibit on women’s suffrage in Alabama, the post-World War II voting-rights struggle has to loom large.

“It’s often easy to lose sight of the individuals who participated in events like the Selma to Montgomery march … But here in the form of a worn shoe is a piece of history from a 15-year-old young woman, a physical reminder of the rigors and dangers of the march she, her brother, and thousands of their fellow citizens undertook in the spring of 1965. Betty’s shoe, the apron her father made from the clothes worn during the march, and her mother’s poll tax receipt, tie together her personal story with how the march affected both Alabama and the nation,” Kirkland continued.

“I consider it providence that these items have survived all these years, so that through them and her other work Betty can educate a new generation about the hard-won right to vote.”

Anderson’s museum in Camden ties the threads of her family’s history together, from slavery to civil rights and beyond. The historic building suffered extensive roof damage in Hurricane Zeta last fall. Those who wish to support her work can give through an online account established by local friends.