The Museum of Modern Art’s new exhibition, “Cézanne Drawing,” which recently opened in New York, is the most comprehensive exhibition of Cézanne works on paper ever mounted in the United States. The show features more than 250 examples of the artist’s output, lent by public institutions and private collectors around the world, and augmented by MoMA’s substantial holdings.

For those interested in Cézanne and the transition from 19th to 20th-century art, this is an exhibition the likes of which will probably not happen again anytime soon, at least on these shores, and therefore is a must-see. During my recent visit, I was pleasantly surprised to see the galleries filled with people from all walks of life, some knowledgeable about “the painter of apples” and some not, all of whom were admiring and discussing the work of an artist who, he might be surprised to learn, has become something of a household name in the century since his death.

Who Was Paul Cézanne?

Paul Cézanne (1839-1906) was born in Aix-en-Provence, the son of a successful banker and self-made man. Although his father wanted Cézanne to become a lawyer, he eventually acquiesced to his son moving to Paris, just like his close childhood friend, author Émile Zola (1840-1902). Despite his ambitions, including making connections with the Impressionists, the somewhat rough-mannered and eccentric Cézanne never quite made it in the capital, and eventually returned home.

Over time, as he sought to evoke through unconventional means the solidity of three-dimensional forms in two-dimensional images, his work slowly earned greater esteem among the cognoscenti, even as he stayed far away from the rarified salons and café society that had once rejected him. By the end of his life, the supposed country bumpkin was inundated with young Parisian artists making pilgrimages to Provence, trying to grab his attention on his way out of daily Mass as they sought his advice on their work.

Planning an exhibition centered around the drawings of an artist once quoted as saying that “There is no line” might seem a daunting proposition, but MoMA has done a splendid job in making sure that visitors will have plenty of space and opportunity to decide for themselves whether Cézanne truly meant what he said.

Spread through nine interconnected galleries, with separate designated entry and exit points, the show is mercifully self-contained, which keeps down the noise level from things like corridors and escalators just outside. In terms of the arrangement, not only is the art hung on the walls, but tables hold framed works in upright stands. As a result, these objects can be seen from the front and the back, since sometimes Cézanne drew on both sides of a single sheet of paper.

The works on display consist primarily of pencil drawings and watercolors, but there are a few oils as well. These in particular serve to show how Cézanne turned some of his sketches and studies into finished paintings. Placards, wall texts, and a few video installations help explain some of the materials and methods the artist most frequently employed.

It’s the sheer number of objects, however, that is the real selling point of this show. For those familiar with the artist’s life and hagiography, all of the expected Cézanne elements are here. There are plenty of apples, natch, among other still-life items; references to Delacroix and Goya; variations on groupings of bathers and the cupid statuette from his studio; endless views of Mont Saint-Victoire; Madame Cézanne sitting ever patiently; the specter of the old gardener; etc. Even Cézanne’s famous “Memento Mori” skulls are here, in various studies.

Perhaps the most striking of these last is his “Skull on a Drapery” (1902-06), a pencil, watercolor, and gouache work on paper. It depicts a skull resting on a bright, vibrantly patterned piece of fabric, its empty eye sockets turned directly toward the viewer. It’s almost a perversely lively piece, and beautifully executed, the sort of thing one can imagine Frida Kahlo wanting to pin to an ideas board.

As one might expect, there are also many gorgeous Provençal landscapes, often executed in wonderfully spare watercolors. Cézanne frequently used the white of the paper as the ground, leaving significant areas of the sheet completely blank.

It’s the mark of someone who truly understands how to use watercolor as a medium, but it’s unexpected from an artist we associate with landscape oils characterized by heavy outlines, and a palette made up largely of intense shades of ochre, blue, and green, with the paint sometimes (particularly in early and late works) applied very thickly. This is a lighter, pastel-shaded world, so much so that it’s almost the opposite of what comes to mind when one thinks of Cézanne.

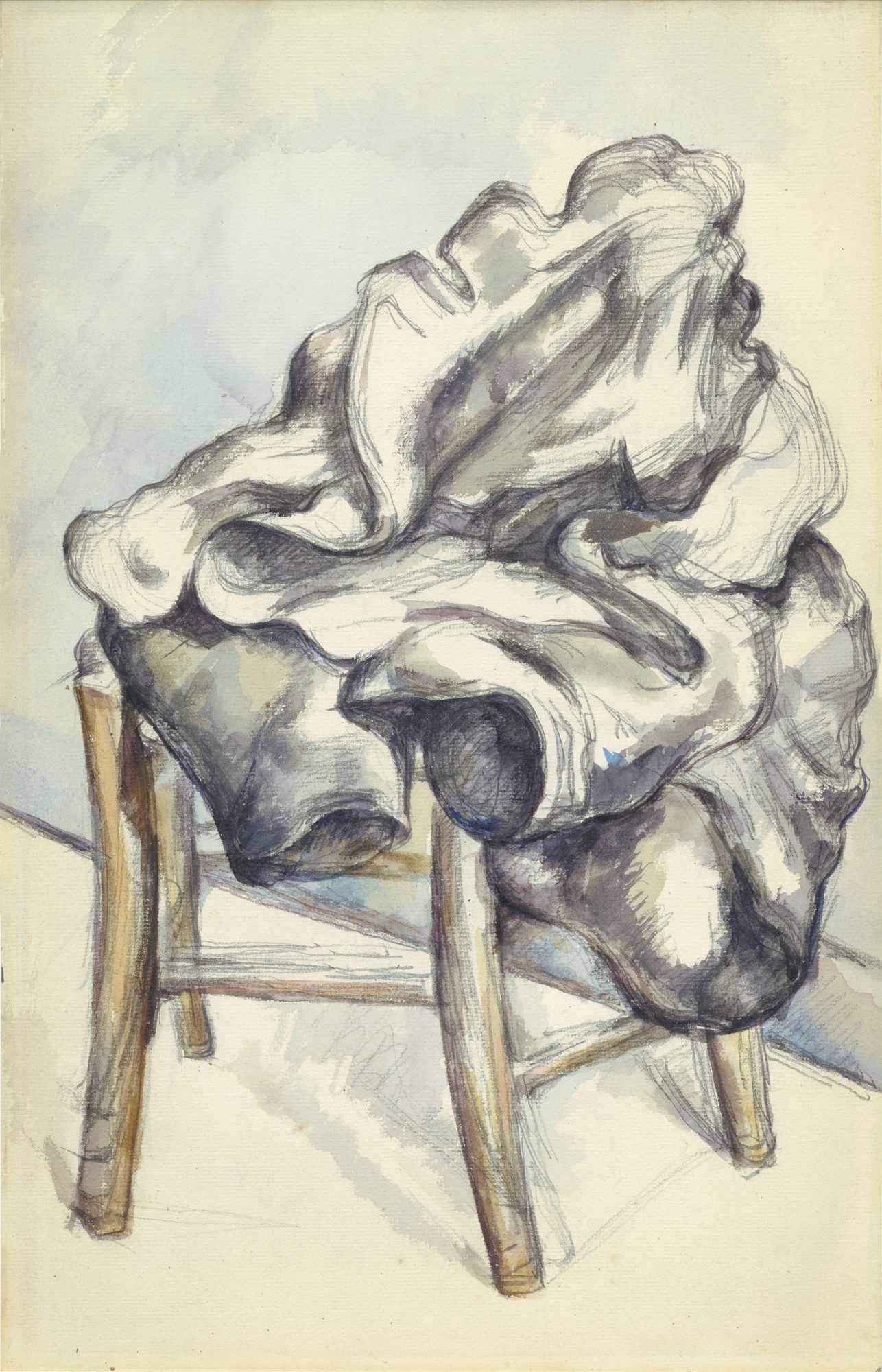

Other objects in the show didn’t “read,” at first, as being by Cézanne either. One in particular that drew the attention of several visitors and myself was “Coat on a Chair” (1890-1892).

Here are heavy contours and a real feeling of weight, which Cézanne always sought to achieve, but looking less like what one might expect from a French Post-Impressionist and more like something one might expect to see from, say, an Austro-German Expressionist. The intensity of the execution, not to mention the difficulty of drawing an amorphous object tossed atop of a solid one, is quite a tour de force.

Similarly, “Three Pears” (1888-90), a pencil and watercolor piece depicting pale green-yellow fruit set against a wonderfully strong, black-and-white arrangement of dish and tablecloth, is not the type of still life that one expects from Cézanne. Like “Coat on a Chair,” it displays a mastery of line, along with an appreciation for the pleasures of a graphically oriented composition.

At first glance, it’s a deceptively simple image, but the more one realizes how architectural it appears, almost like a Baroque sculpture, one comes to better understand Cézanne’s constant seeking out of cubes, spheres, and cylinders in the seemingly mundane and ordinary.

Some of the thematic groupings in the show are particularly appealing, offering the viewer the chance to pause and look at several related pieces clustered together. One example of this is a series of larger works on paper depicting the caverns and rock formations around the neo-gothic folly of the Château Noir, for here you can see why Cézanne was considered by many – including Picasso, Matisse, Mondrian, and others – to be the father of Modern Art. The vaguely geometric abstractions of the surfaces of the rock faces could easily be mistaken for being entirely abstract images.

Perhaps my favorite example of groupings in this show turned out to be a collection of several works depicting potted plants and garden flowers, with the spare and elegant “Pot of Geraniums” (c. 1885) displayed at the center. Amusingly, I noticed two very different visitors simultaneously fixated on this cluster of images: a very pale lady of a certain age, dressed to the nines in sky blue and white linen, and a sunburnt man in a baseball cap, home repair company T-shirt, and cargo shorts. Who knows why either was drawn to this particular group of pieces, and yet here they were, admiring these works together.

Much as I enjoyed the exhibition and learned a great deal, overall Cézanne’s art is still somewhat hit or miss in my book. For every beautiful or challenging work, there are half a dozen pieces that give rise to, at best, a feeling of indifference.

At the same time, there are perhaps lessons to be learned from the fact that he improved quite dramatically as an artist once he stopped caring so much about what others thought of him, and started focusing on what he intimately knew and understood: his hometown, his family and (few) friends, the objects he came across every day.

As this show makes clear, the Cézanne who tried and failed in Paris is far less interesting than the Cézanne who largely kept to himself in Aix-en-Provence. After seeing so many examples in one showing, I might even go so far as to say that I now find Cézanne a much more interesting, challenging, and talented draftsman-watercolorist than he was an oil painter, however heretical that statement to the black turtleneck brigade.

For those not quite as familiar with (or opinionated about) Cézanne, however, MoMA has managed to mount a show with a near-universal appeal. This is not simply a specialist exhibition for Cézanne worshippers or patrons of high art in general. Rather, as the large numbers of visitors seemed to indicate during my visit, if you love to draw, paint, or even just doodle, seeing how one of the most famous and important artists of the past century went about practicing his craft is not only absolutely worth your time, it’s also quite enjoyable.

“Cézanne Drawing” is at the Museum of Modern Art, New York through Sep. 25, and a beautifully illustrated catalog is available through the MoMA Shop, should you be unable to make it to the exhibition.