The heads of Amazon, Facebook, Google, and Apple will make their way to Capitol Hill Wednesday to appear before the House Antitrust Subcommittee. For conservatives, the hearing presents an opportunity to question the powerful companies on a host of topics, including allegations of bias. Bias is a serious area of concern with Big Tech, but it’s hardly the only one.

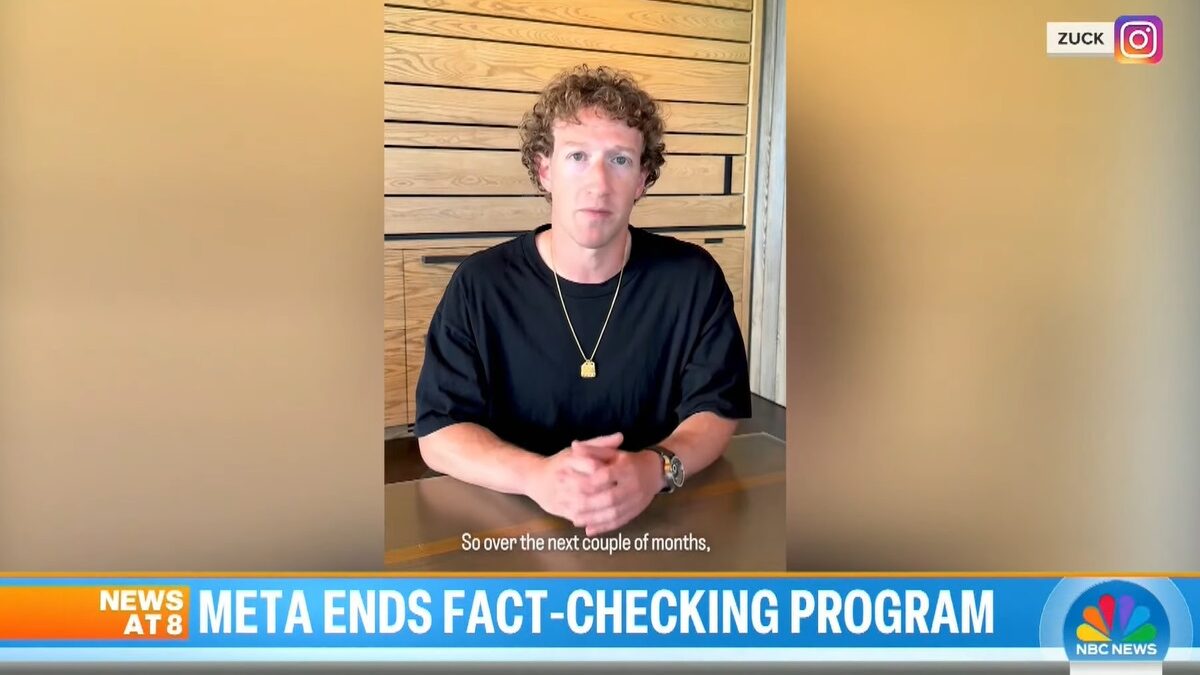

Conservatives have alleged for years that these companies exhibit a bias against conservative points of view despite the fact that entities like Facebook and Google constitute a “global town square” and see themselves as key facilitators of free expression. This allegation has only grown louder as conservative members of Congress were shadow-banned.

Numerous platforms have doubled-down on censoring President Trump and his supporters while leaving other accounts acting in similar ways unmolested. Twitter seems to use an internal blacklist while denying they do so, and Google has responded reflexively to mainstream media demands to de-platform conservative news sites while also appearing to have temporarily suppressed conservative writers in their search results.

The issue is certainly fair territory for members of Congress to investigate and tech behemoths should provide far more transparency. But viewpoint bias is just one concern in a sea of others, and conservatives will waste a tremendous opportunity if they focus solely on the issue of bias. Here are some other areas they should use this hearing to examine.

Using Market Power to Crush Innovation and Competition

In a January field hearing, the antitrust subcommittee heard testimony from small tech businesses who recounted in detail how Apple, Facebook, Google, and Amazon were “wielding their massive footprints as weapons, allegedly copying smaller competitors’s features or tweaking their algorithms in ways that put new companies at a costly disadvantage.” Or, in the words of Patrick Spence, head of the speaker company Sonos, the platforms “leverage dominance in one market to conquer or destroy adjacent markets, especially markets that may one day pose a threat to their dominance.”

Amazon, in particular, is dealing with discrepancies between what they told Congress — that they do not use third-party sales data to set prices for Amazon-branded products — and what their employees told the Wall Street Journal. Amazon is also facing allegations that they met with startups about investing, only to swipe other companies’ ideas for their own product lines.

Google has faced allegations that it self-preferences its search results, demoting non-Google results even when the information contained therein was more relevant to an individual’s search. The Wall Street Journal reported that Google has altered its search algorithm on behalf of big businesses like eBay while modifying search results for terms like “abortion” and “immigration.”

None of this would matter so much if these companies didn’t wield such unprecedented amounts of power. But when Google constitutes 92 percent of worldwide internet searches, the opaque, unaccountable ways the company decides to filter information has tremendous consequences for business, human behavior, and independent thought.

Conservatives are rightly skeptical of government interference in the marketplace. But violations of existing antitrust law in the form of anticompetitive behavior isn’t regulation, it’s law enforcement. As the supposed champions of small entrepreneurs, conservatives should want to ensure that the field of commerce and innovation is fair and equally accessible.

Many on the political right have said for years that people unhappy with social media platforms should just “build their own.” So shouldn’t those same people want to make sure they still can?

The Threat to Individual Privacy

As an industry that makes money from the commoditization of hyper-individualized data, Big Tech knows more about us than any industry in human history. Indeed, Big Tech’s business model is based on knowing where we go (physically and virtually), what we say in our emails and text messages, what we buy, and even what our voices sound like.

This presents huge policy ramifications around what is “ours” and what is “theirs.” Do human beings have a property right to their data trail? Should there be limits on the type of data companies collect, what Big Tech can do with our data, or who they can share it with?

Consider that under a provision of HIPAA, hospital chains have shared the names, dates of birth, and medical histories of up to 50 million Americans with Google without the knowledge or consent of the patients or doctors. Google won’t say what they’re doing with the data, or the data they’ve recently acquired on 28 million users of Fitbit. In this bizarre legal landscape, Google has a right to your medical record, but you don’t.

These companies are also serial violators of individual privacy, despite presenting themselves as the opposite. Google reads our emails. Facebook reads our texts. Google still tracks the location of users who turn off geolocation services.

The huge uptick in students using G-suite to learn from home during the COVID-19 pandemic has allowed Google to collect a staggering amount of data on children — including internet history and voice recordings. Cynically, the company recently used privacy as a smokescreen to kick competing third-party advertisers off of its Chrome browser.

Thanks to its acquisition of DoubleClick in 2007, Google also tracks users across the web. After swearing to the Federal Trade Commission that they’d never co-mingle the data of billions of internet users with the platform data of people using their Google-branded services (Gmail, Google search, YouTube, etc), they quietly did it anyway in 2016, with no consequences.

The power companies have over individual privacy and data is both unchecked and largely unexplored by Congress, and it’s grown far beyond the days of merely “opting out.” If you’re still under the impression that you even can opt-out, try it.

Big Tech’s Entanglement With China

China is increasingly becoming the chief U.S. antagonist for the 21st century. The trouble is, Big Tech has already made its alliances with Beijing. Apple has outsourced much of its manufacturing there and has a troubling pattern of acquiescing to China’s demands on things like privacy and data storage.

As Hong Kong residents protested for their freedoms last fall, at the request of the Chinese government, Apple quietly removed an app from its store that helped protestors evade police. This is par for the course for Apple, which dutifully pulled 25,000 apps from its Chinese app store after the Chinese government declared them “illegal” in 2018.

Google was busted — by its employees — for developing a censored search engine for China’s Communist government. And while the company won’t work with America’s defense department, it has no problem working with the Chinese military.

In a particularly damning discovery last year, it was revealed that Google, Apple, and Amazon have been facilitating the sale of apps the Chinese government uses to suppress and imprison the country’s Muslim population. Tech companies have also been accused of using the forced labor of persecuted minorities to build their devices. As one tech analyst put it bluntly to the Senate Judiciary Committee last year, “China imprisons and tortures and kills religious minorities and political dissidents, and it’s using compliant companies to do this at scale.”

As China increasingly cracks down on demands to access the data of companies doing business within their borders, the risk for American tech companies doing business in China grows. How these companies intend to secure the privacy of their users, technology, and values is up for debate.

Keeping Policy Apace with Big Tech’s Power

The sheer scope of Big Tech’s massive influence and unprecedented power over individuals as well as society is becoming frighteningly clear. Efforts to force this hearing into the frame of “private companies versus the government” or “appropriate or inappropriate uses of antitrust law” are distractions in the face of what lawmakers should be focused on: investigating the intersection of innovation and power, and discerning what is merely commerce versus what is a collective corporate action to change the nature of a democratic society and a free people.

Lawmakers are exactly that: the makers of laws. Their job is to investigate and identify threats to the American way of life as we have determined it and take the necessary steps to protect it. This hearing presents an opportunity for them to gather data points to that end. They shouldn’t waste it.