When social justice activist and lawyer Derecka Purnell was just 12 years old, she and her sister watched a police officer shoot a young boy in a city recreation center because he had ignored the basketball sign-in sheet. This jarring, emotional, and deeply unsettling story was published July 6 at The Atlantic, in the section reserved for ideas, under the bold, attention-grabbing headline, “How I Became a Police Abolitionist.”

Purnell’s deeply personal story of shattered innocence and shattered bones at the end of a policeman’s gun was shared widely among top journalists and activists. “I started her article thinking abolition was impossible and ending thinking it must happen,” the president of a social justice think tank at Harvard wrote on Twitter, quoting his mother. “This is a beautifully written piece,” the Atlantic’s constitutional law editor agreed. “Derecka is the future,” an activist journalism executive declared.

There’s a major problem with Purnell’s story, however. Based on a Federalist investigation of newspaper archives and the police department records, and questions to The Atlantic, the police union, and the office of the mayor, it does not appear to have ever happened.

An Investigation

“The first shooting I witnessed was by a cop,” Purnell, a widely published Harvard Law and Berkeley graduate who is now a columnist for The Guardian, writes. “I was 12. He was angry that his cousin skipped a sign-in sheet at my neighborhood recreation center. I was teaching my sister how to shoot free throws when the officer stormed in alongside the court, drew his weapon, and shot the boy in the arm. My sister and I hid in the locker room for hours afterward.”

“The officer,” she continues, “was back at work the following week.”

Purnell has led a prolific career, including writing for The New York Times and time at the helm of The Harvard Journal of African American Public Policy. Because of her impressive rise from poverty, she’s been the subject of profiles and has been asked to write more than one personal essay on why she is an activist. Despite this, and despite this memory’s seeming impact on her life, her article in The Atlantic is the first mention it ever earns in her publicly available writings. In fact, it appears to be the first mention of the incident in any publicly available record The Federalist was able to uncover.

Purnell paints her story of police dependence in the polluted and impoverished St. Louis neighborhood she lived in. “We called 911 for almost everything except snitching,” the essay opens. “Nosebleeds, gunshot wounds, asthma attacks, allergic reactions. Police accompanied the paramedics.”

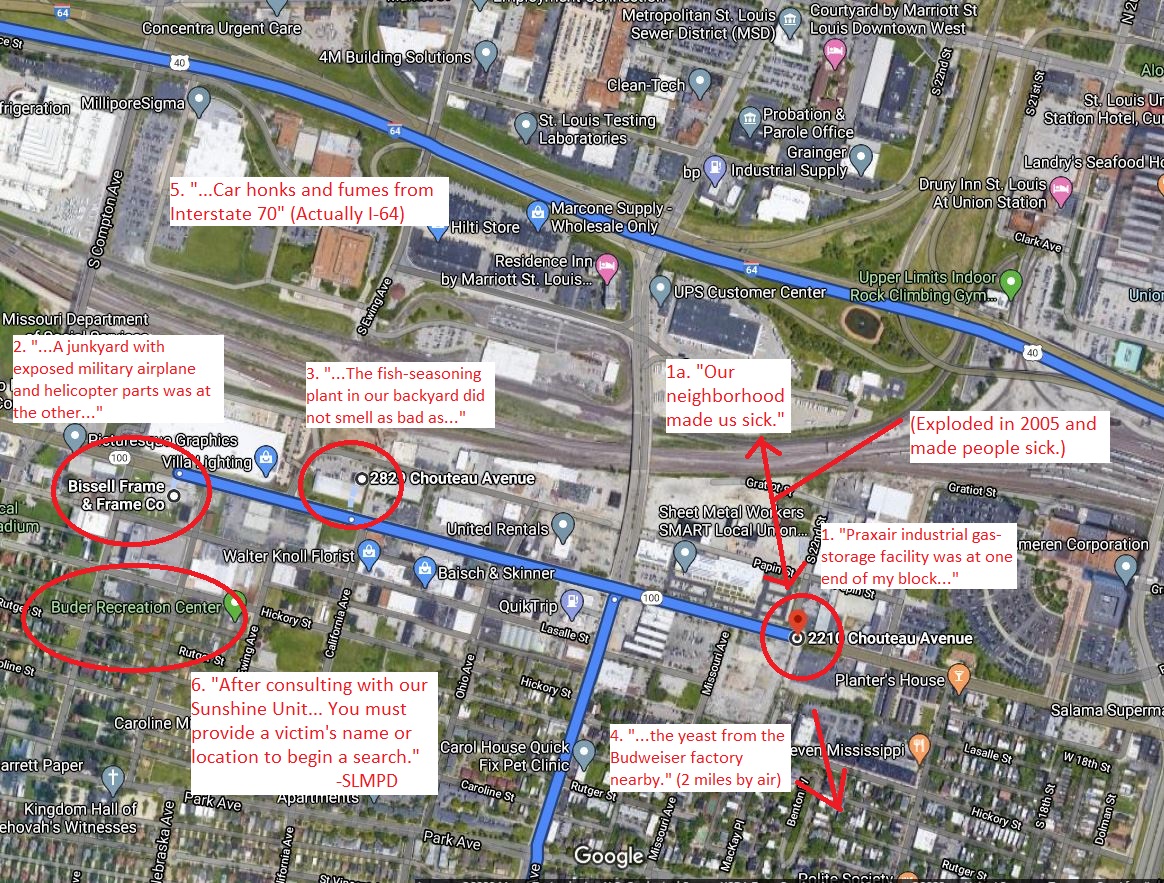

“Our neighborhood made us sick. A Praxair industrial gas-storage facility was at one end of my block. A junkyard with exposed military airplane and helicopter parts was at the other. The fish-seasoning plant in our backyard did not smell as bad as the yeast from the Budweiser factory nearby. Car honks and fumes from Interstate 70 crept through my childhood bedroom window, where, if I stood on my toes, I could see the St. Louis arch.”

An Aircraft Boneyard

In The Atlantic, Purnell says she was 12 years old. While her current age is not public information, when she sat for a Kansas City Star profile in 2014 her age was reported as 24. Based on this, we can safely assume the alleged police shooting occurred between 2001 and 2003. A broad search for “police” and “recreation center” in the St. Louis Post-Dispatch’s archives for those years yields 37 results. Those results include voter guides, community events, feel-good stories, budget updates and all the standard business of local news coverage, but no stories remotely resembling a police officer shooting a boy.

It’s worth noting that 2001-2003 is not, say, 1971-’73 — in addition to a still meaty local media, the United States was on edge: George W. Bush was in the White House, the country was involved in one war and on its way to another, and the police state’s response to terror attacks was under close scrutiny. In all likelihood, a police officer shooting would merit at least one local news story, but it’s possible that more specifics were needed.

Due to confused memories or exaggerations in her story, her neighborhood is a difficult place to nail down despite the vivid details. In numerous profiles and biographies, including the Kansas City Star profile, she is described as living on the south side of St. Louis, Missouri, though she has also said she was moved around traumatic foster homes in her childhood. While Route I-70, which she says she lived in the fumes of, for example, runs through the northern part of the city, the Budweiser factory is four miles south of its closest bend.

Additionally, there are multiple Praxair stores in the city (and no longer any industrial storage facility). A strong clue, however, lies in the “junkyard with exposed military airplane and helicopter parts at the other” end of her block. A military aircraft boneyard in plain sight in a city is a rare thing.

Indeed, there is a place that fits the bill in the south side of St. Louis that can be seen from Google Earth. Though its proud owner would disagree with Purnell’s description of the collection of old military aircraft he has been building since the early ’90s, it’s easy to see how a child might think otherwise.

Just a three-minute walk up the road sits Andy’s Seasoning, a multi-generation family business specializing in fish seasoning. While it is not the only spice manufacturer in the city, it is the only one focused mainly on the fish seasoning, which Purnell mentions being manufactured “in our backyard.”

And a mile down the road is a burnt-out lot that in the 2001-2003 time-frame housed “a Praxair industrial gas-storage facility.” The lot is burnt out and abandoned because in 2005, the St. Louis Post-Dispatch reports, the facility exploded in a massive ball of flame, shaking “the surrounding neighborhood,” shooting “debris like missiles” throughout the area, delaying the Cardinals game over a mile away, triggering a fatal asthma attack in one resident, and spreading fear of asbestos and other deadly chemicals through the city.

The fish seasoning plant and airplanes aren’t exactly at the end of a block, but at 3/4 of a mile apart, they’re close enough to enclose a neighborhood. And while the fish seasoning plant isn’t in the backyard of any residential homes, it’s just two and a half short blocks from the outskirts of the neighborhood.

Purnell must have misremembered the name of the interstate that “car honks and fumes crept though [her] childhood window,” but Interstate-64 is just half a mile north, joining the railroad to wall the neighborhood off from the city’s center. And while the Budweiser factory was that smell she says overpowered the backyard fish seasoning is over two miles away by air, its prominent place in St. Louis history deserves mention in any story of the city.

Based on the vivid-if-imprecise description of her neighborhood, her “neighborhood recreation center” was most likely the Buder Recreation Center. Having a location allowed The Federalist to launch a Sunshine Law records request with the St. Louis Police Department, but just in case the sisters had attended a different rec center, there was one more that could be walked to from the general neighborhood without having to cross a major highway. Both community centers were included in the records request.

The results, though, do not support a shooting, and certainly not one involving a police officer shooting an unarmed child in front of witnesses.

Between 2001 and 2003, there were 23 police responses to the Buder Recreation Center and 38 to the 12th & Park Recreation Center. The nature of the calls cover a range of incidents, from accidents to domestic disputes, from pedestrians in need to suspicious vehicles, from larceny to arson. None of the police responses, however, involved a shooting except perhaps one attempted suicide at the 12th & Park rec center.

(0) Results Match Your Query

“I’m a little bit at a loss for words here because the shooting of a young boy by a cop in a St. Louis rec center, even if it had happened 20 years ago, I feel like that would be in my mind somewhere,” mayoral spokesman Jacob Long, a former reporter, told The Federalist over the phone. “That does not sound remotely familiar, and I’m from here … I was here in 2001, 2002, 2003.”

“You went to the right place to try and verify that incident, the police department,” he added, independently identifying the neighborhood The Federalist identified, based on the article’s description. “The current mayor wasn’t even the mayor at that time.”

“That predates my tenure here but I don’t remember that even as a consumer of local news.” Jeff Roorda, a former police officer, Democratic state representative, and current executive director of the St. Louis Police Officers Association, added in an email.

The Federalist sent two emails to Yoni Appelbaum, The Atlantic’s editor of the Ideas section, asking if the magazine fact-checked the claim:

…can you detail the fact-checking process for this story?IE which editor was tasked with confirming the details alleged in the story?

Did The Atlantic verify the details of the shooting with local authorities?Did The Atlantic speak to any other eyewitnesses to the alleged shooting, or to any witnesses who recalled the incident and corroborate the claims made by the author of the story? Did The Atlantic speak to the police officer allegedly involved in the shooting, or to any of his representatives, legal or otherwise, prior to publishing the story?

Can you provide the name of the officer responsible for the alleged shooting? Can you provide the name of the recreation center where this allegedly happened? Can you provide a police report of the incident? Can you provide the date of the shooting?

Appelbaum did not respond. On Friday morning after publishing, Purnell responded to a Thursday afternoon request for “any other stories or corroboration of this incident,” writing, “Hi Chris – the Atlantic found it. Take care.” The Federalist sent a follow-up to Appelbaum inquiring on if he this is true, and if he plans to answer any of Thursday’s questions. He has still not replied.

In her essay, Purnell used the story of the shooting to ask readers to consider the innocent victims of policing, going on to make the case for abolishing the police. If her ideas had been implemented before her experience, she writes, “I wouldn’t have hid in the locker room for hours because of a police shooting, and maybe my sister would have a better jump shot.”

This post has been updated to include Purnell’s Friday morning response, and The Federalist’s follow-up to Appelbaum.