During the worldwide COVID-19 panic, many bishops have decided to suspend giving Holy Communion, performing baptisms, providing absolution, and anointing the sick (except in cases of death). Generally speaking, unlike during past pandemics, the Catholic Church has shut down the sacraments during thisone.

While the bishops mean well, there is no practical, canonical, moral, theological, psychological, and historical reason why they should cease administering the sacraments. Their decision to do so should be reconsidered.

1. Sacraments Are Essential No Matter What Politicians Say

Stores and services the state considers essential, such as medicine, abortion clinics in some states, fast food, automotive shops, and gun retailers all remain open. Someone can get his oil changed, buy a shotgun, and order a Big Mac, but in many dioceses cannot receive the sacraments except in cases of death.

Other essential services are using precautions while carrying out their normal activities; parishes could do the same. By suspending the sacraments and restricting people’s spiritual, physical, and psychological essentials, the church’s message to the world is that the sacraments are not essential.

2. Canon Law Says Sacraments Are Essential in Times of Need

The Catholic Church’s Code of Canon Law states, “Sacred ministers cannot deny the sacraments to those who seek them at appropriate times, are properly disposed, and are not prohibited by law from receiving them.” The right to the sacraments flows from baptism. Baptized Christians, therefore, have a right to them.

Someone could interpret this law to mean that asking for a sacrament during COVID-19 is unreasonable and made at an inappropriate time. That presupposes every request by every person in a diocese during a pandemic is made at an inappropriate time.

It further presumes a priest cannot make something inappropriate appropriate for a person’s well-being. Alternatively, and I am not a canon lawyer, a person making a request for a sacrament during a pandemic is made at an appropriate time because it is then, and especially then, that someone needs divine help.

3. If the Unfaithful Get It, So Should the Faithful

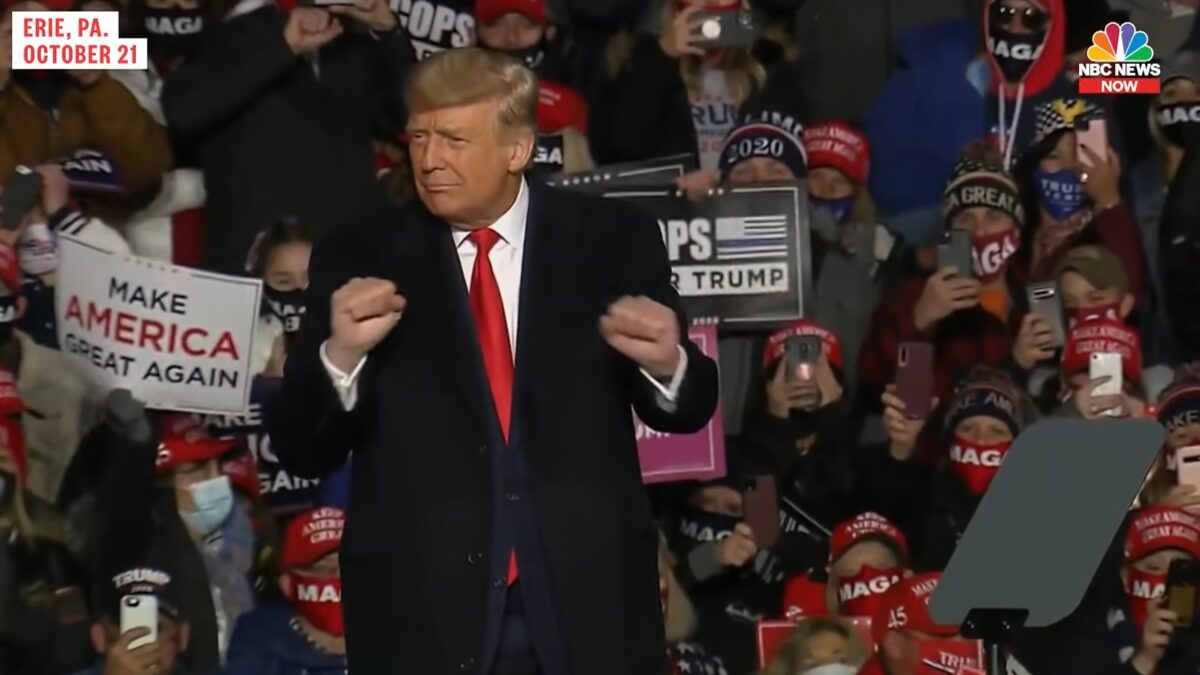

Unless bishops widely suspend sacraments for the unfaithful during a moral pandemic, they should not for the faithful during a physical pandemic. For example, “Catholic” pro-abortion politicians.

Under Canon Law, heretics incur automatic excommunication. Heresy is an obstinate post-baptismal denial of or doubt concerning a truth that must be believed. Statements by “Catholic” pro-abortion politicians concerning the welfare of babies is a denial of several truths and arguably rises to heresy. Every election year, people debate this.

Also under Canon Law, a person whose public statements gravely injure good morals “is to be punished with a just penalty.” Commentary on this section gives promoting pornography as an example. Public statements by politicians supporting abortion, while simultaneously expressing they are Catholic, gravely injure good morals. Yet some claiming to be Catholic hear this and believe it is OK to still support killing babies and vote for pro-abortion politicians.

In the past, the Conference of Catholic Bishops stated the decision to withhold Communion from pro-abortion politicians is left to individual bishops. United, bishops should do that, before withholding it from the faithful.

4. The Sacraments Are the Heart of Our Faith

The whole liturgical life revolves around the sacraments. They sanctify humanity, establish communion, and strengthen faith. The church, quoting scripture, teaches sacraments are powers that flow from the body of Christ — powers that are life-giving.

The church also asserts sacraments are necessary for salvation. For example, the Eucharist strengthens faith, heals, brings unity, and forgives venial sins. Also, Jesus, as physician of body and soul, gave the church confession and the anointing of the sick.

The “Catechism of the Catholic Church” discusses anointing the sick in detail in relation to Christ as physician, strengthening the ill, giving the sick courage and peace, and conforming them to Christ’s resurrection. Confession not only is the only ordinary means to restore a sinner to God and the church, it revitalizes the life of the church. It also repairs psychological wounds, reconciling the confessor to herself or himself, hearing the words of absolution.

5. Denying the Sacraments Could Push Catholics Elsewhere

Catholics are permitted by law to go to a non-Catholic priest for sacraments if they are valid, when a Catholic cannot physically or morally go to a Catholic priest, when necessity requires it, and when there is no danger of indifferentism. Turning off the spigot of sacraments in the Catholic Church may force someone to approach the spigot of valid sacraments in another church.

6. The Church Historically Preserved Sacraments In Pandemics

We should model the examples of administering the sacraments and service to the ill from past pandemics. As Black Death swept through Europe, the church permitted priests to tend to the sick and provide sacraments. Many of those priests became sick and died, so the laity began to die without confession or other sacraments. The mortality rate for priests in the Diocese of Bath and Wells increased so much that the Bishop of Bath and Wells, concerned for the salvation of souls, permitted confession to laymen, to include women, when someone could not obtain a priest.

In the 1500s, a plague hit Milan. This plague is now called St. Charles Borromeo’s plague because of his tireless devotion to treating the sick. In one case, doctors refused to treat the sick, and St. Charles protested. Civil authorities then permitted him and priests to attend to them. Priests would climb ladders to give the Eucharist to the sick.

More recently, in the early 1900s, when the Spanish flu hit Philadelphia, civil authorities suspended church services. The archbishop offered his buildings as temporary hospitals. Priests, nuns, and the Society of St. Vincent de Paul cared for the sick. Two-thirds of the sisters in the diocese attended to the ill.

When civil authorities closed churches in New Orleans, priests protested. In Wisconsin, the archbishop of Milwaukee complied with a civil order to close churches to public services, but he continued confessions and Holy Communion.

I don’t criticize any one bishop, and this is not to say that all sacraments are prohibited in all cases. Most bishops make an exception for cases of death or extreme illness. But the church should be clear in its voice that the sacraments are essential and necessary to life, and that they will continue no matter what, but with safeguards. The sacraments are more important than any other available goods or services.