The unimaginable scene of a virus that has left 11,000 Americans dead and an economy paralyzed leaves the nation wondering how this could have possibly happened. The easy target is the president of the United States, who repeatedly assured raucous campaign crowds and the nation that the virus was under control before it wasn’t.

It’s charged the president ignored warnings and painted a rosy picture of an unfolding crisis in a short-sighted attempt to preserve the economy and a beloved stock market. But who, exactly, was sounding the alarm?

The World Health Organization (WHO) would seem to be an important piece of the global early warning system. Unfortunately, this organization has come a long way from its early days as a virus hunter.

Founded in 1948, the WHO is governed by a 194-nation World Health Assembly, with now lofty and expansive public health goals. The world may need virus killers, but the WHO has a larger mission, as evinced by its multitude of stances designed to promote social and economic egalitarianism. Not surprisingly, the WHO has struggled to handle recent infectious outbreaks.

A Poor Track Record with SARS in 2003

The SARS outbreak of 2003 that began in Guangdong, China began as a cluster of unusual pneumonia cases in November of 2002. From the get-go, the Chinese government’s response was to obfuscate and hamper all efforts to shed light on the problem.

The world might still be blind to the actions of Chinese officials if not for an elderly partially retired physician named Jiang Yanyong, who emailed concerns of official undercounting of cases to Chinese and Hong Kong television stations. The WHO was blind to what was happening in China. SARS was only discovered after it had escaped.

Local health officials in Guangdong had attempted to inform the central government of a fast-spreading pneumonia-like illness in late January. Officials sent a bulletin in response to local hospitals, but did precious little else.

In the meantime, SARS was infecting hundreds of patients, moving rapidly throughout China, Hong Kong, and ultimately 16 other countries. It took until April for China to allow the WHO to even go to Guangdong and neighboring Hong Kong. Stability in the form of tourism, trade, and continued foreign investment were on the line. The potential for a global pandemic, even in 2003, was a secondary concern.

WHO Was Not an Innocent Bystander

The WHO at first glance seems an innocent bystander to Chinese obstruction until one considers the story of SARS in Taiwan. Taiwanese health officials attempting to inform the WHO of their cluster of cases were rebuffed and asked to report their findings to the central government in China instead.

You see, the allegedly apolitical, humanitarian, and guided-by-science WHO doesn’t think Taiwan exists because China doesn’t recognize Taiwan’s independence. The WHO even refused to publicly report Taiwan’s cases of SARS until public pressure prompted numbers to be published under the label of “Taiwan, province of China.”

Interestingly, the wide berth afforded China does not extend to Israel. The WHO has repeatedly singled Israel out as an alleged violator of Palestinian health rights in the “Occupied Palestinian Territories.”

Clearly these matters are worthy of debate, but why would the WHO put its thumb on the scale? The answer, increasingly obviously, is that the WHO is a political organization that attempts to give its political preferences the veneer of objectivity using the label of science.

WHO Also Failed in the 2013 Ebola Outbreak

The Ebola outbreak of 2013 provides yet another window into the WHO’s lethal failings. One of the important controversies at the time related to how the virus spread. An excellent 2015 New Atlantis article dissects the controversy of transmissibility, and concludes the available evidence at the time could not rule out through-the-air transmission.

Of particular concern was evidence from the field about health-care worker infections. Health care workers who did not wear maximal Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) in the form of respirators to filter out airborne transmission were infected with Ebola at a high rate.

Doctors Without Borders treatment centers that mandated full-body hazmat suits and respirators only had 23 of their 3,300 staff members infected, while local hospitals with significantly less PPE saw 869 health-care workers infected.

Rather than err on the side of safety, the WHO ignored this evidence. Local health officials and administrators followed their lead for a similar approach in their hospitals. First responders paid the price. The SARS outbreak in Canada was notable for the number of health workers who were infected and succumbed to the disease, in part, because the initial responders to the crisis relied on PPE guidance that wasn’t adequate.

The CDC Is In on This Action

To be fair, what’s on display here is a broader institutional malady. The U.S. version of the WHO, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, took a similar stance with another controversial topic—quarantines for health-care workers returning from treating patients with Ebola. Four states—New York, New Jersey, Florida, and Illinois—instituted policies to quarantine anyone who had contact with someone infected with the Ebola virus while in west Africa, including medical personnel who cared for patients.

No less than the Obama administration, backed by the CDC, attempted to quash these policies, arguing this would serve as a disincentive for U.S. health workers to travel to Africa to combat the disease at a time this help was sorely needed.

The argument made by many, including the now famous Dr. Anthony Fauci, was that Ebola could only be transmitted by those who were symptomatic, so it was anti-science to consider mandatory quarantines. Of course, crossing the threshold from asymptomatic and not infectious to symptomatic and infectious isn’t a sudden process, and as the history of science repeatedly shows, theories have a way of evolving with time.

The head of the CDC at the time, Tom Frieden, had initially recommended that health-care professionals not use respirators when taking care of patients with Ebola. It took two health-care workers in Dallas contracting Ebola from a patient for the CDC to change its recommendations in October 2014.

An important recurring theme with viruses may be to follow what people do rather than what they say. This is Tom visiting a Doctors Without Borders Ebola treatment center in August 2014, at a time the CDC was saying a surgical mask was adequate to care for these patients.

More Concerned about Population Control than Illness

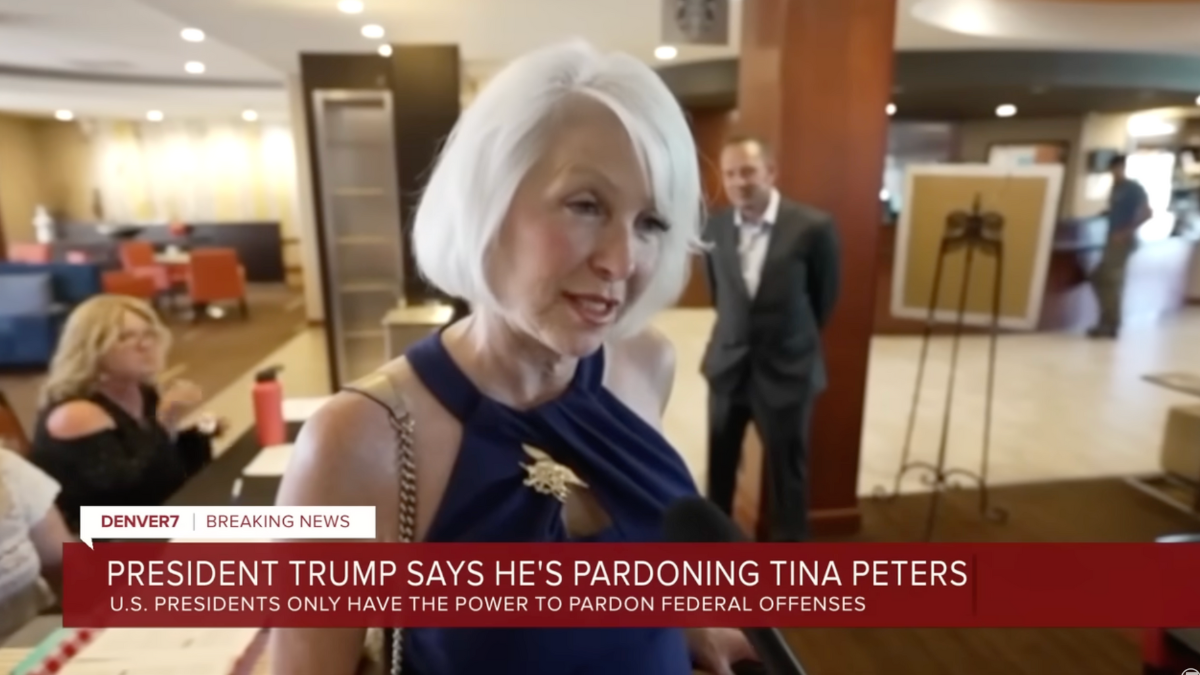

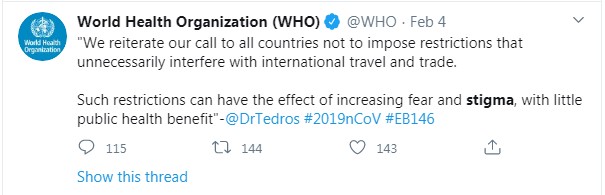

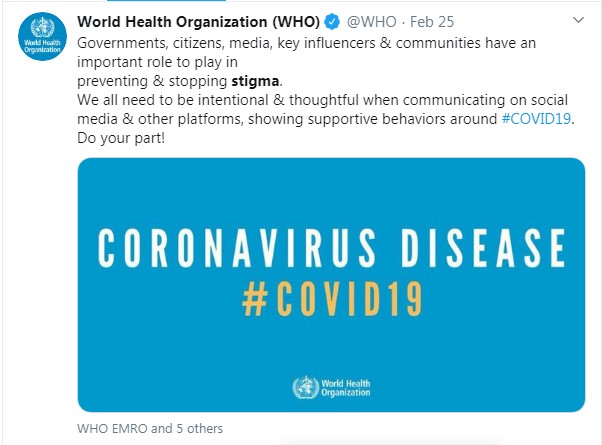

The charitable take is that institutions like the WHO and CDC are simply coming down on the wrong side of contentious scientific debates. But there is a persistent directionality to these mistakes that betrays a current of ideology. A review of the timeline of announcements by the WHO after the COVID outbreak shows an organization more concerned with avoiding panic and stigma than the virus.

The tenor here was clearly to calm rather than sound an alarm that may reduce tourism or trade or anger politicians of member countries the WHO relies on for funding. This is precisely backwards. During global health emergencies, the public and the political class need organizations like the WHO to sound the alarm and to do so free of politics.

And they can’t. In the 2015 New Atlantis article about the mishandled Ebola outbreak mentioned above, Ari Schulman, wrote: “the broader institutional factors that led to the failures of public health in 2014 remain unchanged. We must understand and fix these problems, for the next outbreak may be of a disease more contagious than Ebola, and even worse understood.”

Tragically, these were prophetic words. There were no urgent missives addressed to the people or the politicians of the United States with warnings of what was to come with the coronavirus, because the WHO was too busy reassuring the world from its perch in Geneva that the situation was under control.

China Scrambles While the WHO Sits Quietly

It was in late December that multiple doctors in China first learned of a cluster of cases of pneumonia related to a Seafood Market in Wuhan. News circulated via physician WeChat groups of a new pneumonia with entreaties to wear masks and avoid the market. Shortly after, a Chinese lab isolated and sequenced a then-unknown virus on Jan. 5, two days prior to China’s official announcement that mysterious pneumonia cases in Wuhan were caused by a novel coronavirus.

Recognizing the importance of the findings, the researchers reported results to China’s National Health Commission the same day. After six days without a response, the Shanghai lab made its finding public on Jan. 11, and released its data on open-access data repositories for the world to see.

It was only then that the Chinese National Health Commission announced it would release the genome of the virus to the WHO. The following day, the Shanghai lab found itself shut down for “rectification.” The ill patient the samples had been derived from had been admitted to Wuhan hospital on Dec. 26.

As an ever-increasing number of patients swarmed local hospitals, no evidence of larger public health measures to mitigate the virus were evident. A lunar year banquet scheduled in Wuhan proceeded as planned Jan.18, and 40,000 families gathered to share food. According to a New York times study of cellphone data from China, 175,000 people left Wuhan on Jan. 1 alone.

It was not until Jan. 20 that the lead physician in China in charge of the virus response confirmed that human to human transmission was possible. By then, Wuhan hospitals were being flooded with patients and the virus was popping up all over China. Scrambling to contain a situation spiraling out of control, China imposed a lockdown of 60 million people in Hubei province Jan. 23.

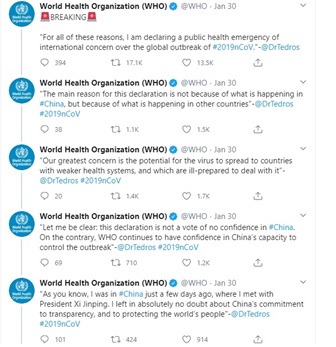

The unprecedented actions China took should have signaled to the WHO and the rest of the world that everything was most definitely not okay. The WHO did convene Jan. 30 to declare a “Public Health Emergency of International Concern,” but the public comments were focused on signaling to the world that China had the situation under control, the announcement was not cause to institute travel or trade restrictions with China, and that the declaration was only being made out of concern for the health systems of developing countries.

WHO Was Just Plain Wrong

The reality was that China had bungled the response badly. Clearly the people on the ground felt a sense of urgency when a potentially novel SARS-like virus was identified, but they were let down by a bureaucracy that was lethally slow.

When it was clear the extent of the outbreak couldn’t be hidden any longer, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) quickly moved launched a public relations campaign framing the story as an unprecedented crisis, turning the narrative into lives saved because of the CCP’s bold actions. The WHO, constantly concerned with appeasing China, was a willing cheerleader, content to tweet about handwashing, leaving the hard decisions about containment and mitigation of the virus to individual countries.

Countries like South Korea, Singapore, and Taiwan had an infrastructure and urgency driven by the prior brush with SARS and started widespread testing, aggressive contact tracing, and isolation of positive contacts. The WHO frequently mentions the success of South Korea, and amplifies Korea’s test everyone strategy, but leaves out the fact South Korea banned travel from Hubei Province in early February.

The forgotten country Taiwan also has been remarkably successful in controlling the outbreak. Not surprisingly, Taiwan began to screen passengers from China Dec. 31, banned Wuhan travellers Jan. 23, suspended tours from China Jan. 25, and restricted all Chinese visitors Feb. 6. Taiwan’s exclusion from the WHO may have protected them from the advice of an organization that didn’t label the worldwide explosion a pandemic until March 1.

Listening to WHO Dulled Our Responses

The major problem here is not so much the WHO as it is the masses of local health officials who take their guidance from the soothing “evidence-based” proclamations of the organization. This is why in the midst of a pandemic, school officials are worried about free lunch programs and adequate home internet access while leftist politicians are rushing to local Chinatowns to have photo-ops to discuss stigma and xenophobia.

It becomes a little harder to get angry at Trump for reassuring his fans everything was going to be just fine when the WHO was saying the same thing. What warning was the president ignoring? Recall that it took the WHO until March 11 to even declare a pandemic. Reports of intelligence officials warning Trump and Congress of the danger of the unknown virus have been leaked, but if anything, bolster the claim that Trump was listening (wrongly) to the consensus of scientists on the level of threat posed.

The important lesson here is to break the institutional groupthink that dulled our senses. Despite knowing little about the virus, when it was finally disclosed the WHO almost immediately began to blindly reassure everyone, ignoring alarming signals for months.

The fervent hope is that the health system bends, but does not break with the test it has been given. Reasons for optimism abound as the medical community and the nation exert a massive effort to overcome this public health crisis.

The failure of the responsible institutions will hopefully not fade from memory anytime soon. If we are to avoid the next pandemic, it will be because we listen to those at the coalface and ignore the empty suits from Geneva and their even emptier proclamations.