Washington, D.C. — What does it mean to live in a city under lockdown? It’s a question most Americans haven’t considered. Most free people, really. Martial law, siege, plague — these are the stuffs of history, fantasy, and foreign lands.

At least they were. Today, as cities are shutting down and police are turning out-of-staters around at our borders, we’re suddenly confronted with the real question: What will be I able to do under quarantine?

States and localities are prone to treat things differently. Interviews with friends, colleagues, and passersby, combined with personal experience and pictures from inside the nation’s capital, show a slowed world where there are no police road blocks and more is deemed essential than people might have guessed.

The airports are nearly empty, but you can catch your flight there. You can run any other city errands too, so long as the business is open. There are no police checking your papers in Washington, although core essential employees such as news broadcast technicians have been given a government waiver declaring them such. And just before 6 a.m., the working-class highway traffic gives no sign anything is wrong, although by early afternoon the city’s roads are largely empty of drivers.

Walkers, families, and people on local errands keep the sidewalks bustling, while a seemingly endless stream of fit neighbors jog by to make up for missing the gyms their government closed as nonessential. As March came to a close, renters and owners moving out of their homes needed not fear: Moving companies are deemed essential, even in New York City, and their vehicles idle alongside delivery trucks and police cars on quiet streets.

Grocery stores have lines out the door even after the major prepping and disappointing hoarding stories left the news, but now the line is to enforce social distancing and disinfect the hands of sometimes-masked shoppers before they enter. It’s still rare to find toilet paper or a full chicken.

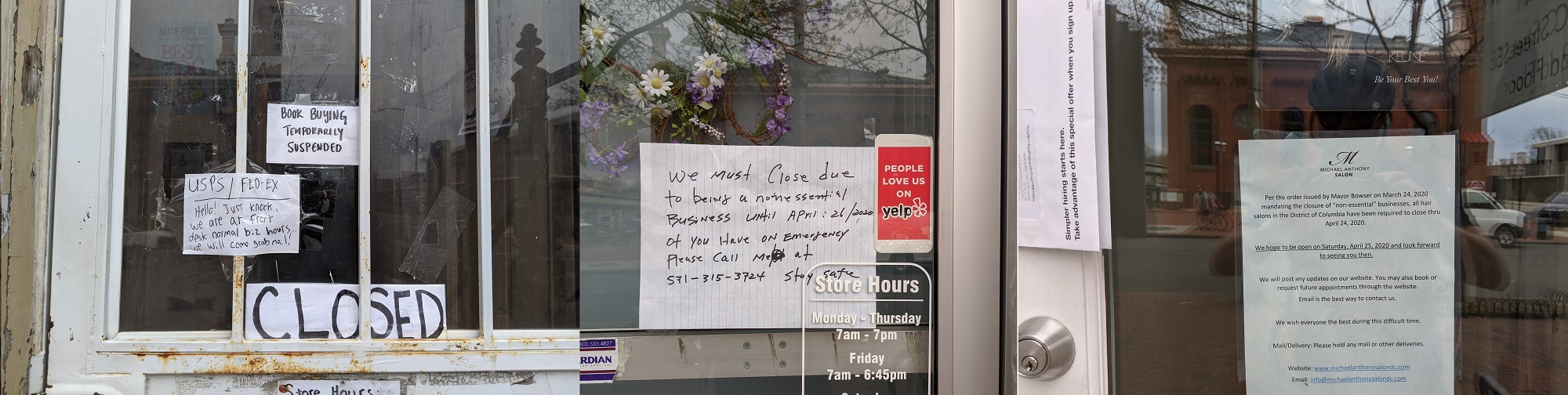

The grocery store is a far cry from the nearby used book store, dry cleaner, and salon, which are among the hundreds of businesses the city deemed non-essential. While some dry cleaners have begun to reopen for limited hours, look around and you’ll notice how many men’s haircuts have grown long and shaggy over the past few several weeks.

While the weekend flea market and crafts stalls typically across the street are missing, the farmers driving in from the country can still peddle their wares, and even the coffee stand remain open.

All food markets are exempted from closure — even the flower shop inside Eastern Market. “We’re in the food hall,” its relieved owner tells me. “Trader Joe’s can still sell flowers, so we’re allowed to too.” Despite the missing crowds, business is actually up, optimistic stall owners say.

“I’m predicting a 5 percent increase for April, especially once the hysteria dies down,” cheesemonger Mike Bowers told me. His grandfather bought the stall for Bowers Fancy Dairy Products in 1964, and Mike is the third generation of Bowers men to own and operate it.

Since the mayor decreed increased enforcement against large gatherings, the market has installed rope barriers to put a little more space between shopkeepers and customers, though on warm spring days the doors remain open, filling the hall with fresh air. “The market is the only place we’re shopping,” local architect and longtime resident James McCrery tells me.

Billy Glasgow’s family has owned Union Meat Co. since 1946, making his one of the market’s longest-running family stalls. A purveyor of everything from pork chops to the coveted Japanese Miyazaki A5 Wagyu, he’s chipper on a Sunday afternoon. Business is “way up,” he says, although most is on weekdays with the weekends suffering a little from the lack of an outdoor market.

“There aren’t any tourists,” he notes when he sees me surveying the lack of crowds. “But they aren’t buying steaks. We’re not like a grocery store where people stocked up on four-packs of frozen steaks — we’re the shop for something nice.” It was a two-inch, top-prime filet for this guy, delicious as always in a homemade version of the blueberry reduction sauce restaurant Acqua al 2 introduced to the world.

Acqua, across from the market and a local favorite for the Hill, has two locations — one in D.C., the other in Tuscany, economies both hard-hit by the coronavirus. Its owners have temporarily shuttered its D.C. location but are taking orders by phone before 3 p.m. for next-day delivery or pick-up at their bar window.

D.C. Mayor Muriel Bowser shut down the courts and citizens are unable to obtain so much as a marriage license, but collecting ticket parking revenues, it seems, was deemed essential. One Capitol Hill police officer complained residents’ continued need for permits is putting lives in danger.

Down toward the Capitol, the bustling bars remained open, but for pick-up only. A divey Hill mainstay since it opened in 1996, the Capitol Lounge has survived two fires and plans to survive one plague, but restaurants and bars in the city are desperate, with layoffs, mounting bills, and creative attempts to keep anyone they can on the payroll.

Fortunately, New York-style pizza joint We The Pizza is humming along on the corner looking almost normal, with customers a little close for corona-comfort as they wait for slices and pies served from behind the counter.

The bank across the street suspended notary services, although the teller window remains open. Nearby, the door of the FedEx is locked but employees allow up to 10 customers in at a time, with carefully marked and roped off social-distancing spots in case a line is forming. The delivery woman who once asked for ID and a signature will now take an obvious adult’s nod and “thank you” through the window. Most social distancing still comes with a smile.

The phone stores are closed, though Verizon is offering same-day delivery on a number of products. The pharmacist and his assistants playfully bicker behind the counter at Pennsylvania Avenue’s CVS Pharmacy; they’re busy wading through the sudden complication of mailing prescriptions to patients.

Up the block, a federal worker is cleaning the Supreme Court’s spring gardens. The court is closed, and most federal employees have been sent home. The long lines of school kids and cherry blossom tourists are nowhere to be seen, although as with elsewhere in the city there is no extra police presence.

Down on the National Mall, usually packed on a nice weekend and absolutely teeming during the spring tourist season, the contrast with normal is stark.

The ever-popular Smithsonian museums, once seen daily with tourist buses, bicyclists, and food carts, are closed as well.

Up from the Mall and across from the White House, Old Ebbitt Grill serves the most meals annually of any restaurant in the country and is the fifth-highest-grossing. On Friday, it was empty, with a side door to the kitchen providing service for pick-up and deliverymen.

Life in the residential neighborhoods is keeping busy, if old-fashioned, but in the District’s commercial areas like downtown and Chinatown, life lies abandoned.

The Capitol One Arena, home of both the Stanley Cup-winning Washington Capitals and The Wizards, usually hosts the city’s largest concerts and other performances. Today, it is closed, along with the other sporting and concert venues.

Across the way, The Loft at 600 F Street and its neighboring National Union Building, both busy event spaces, are shuttered completely, with neither staff nor owner receiving a paycheck until help comes.

“It’s really tough right now,” founder Martin Avila tells me. “A total shutdown of business. You go from a thousand events in a year to absolutely no business whatsoever. But we’re working with our employees, our landlord, and our customers and we’re going to get through this together.”