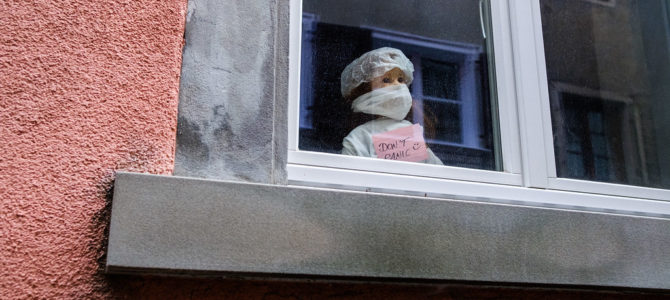

COVID-19 is severe. There is no doubt about that. We are now also learning that it is not a matter of if but when many of us will get coronavirus, whether we develop symptoms or not. Our only hope is to “flatten the curve,” relieve stress on the medical system, and wait for a vaccine.

So, we isolate ourselves and stay at home. As a result, the economy is being devastated. Many people are out of work and unhappy. We accept these inconveniences to allow the medical system to handle the many people who become infected.

But what if I were to tell you that our current isolation strategies may actually result in more deaths from coronavirus itself? I’ll explain.

The only way we are going to beat COVID-19 is by developing something called “herd immunity.” Herd immunity basically means that once a certain percentage of the population develops immunity to a virus, the rest of the population will also be protected. That percentage varies, but is often around 60-70 percent. This is why we don’t need to vaccinate 100 percent of people to eradicate or severely limit the spread of infectious diseases (e.g., polio, smallpox, and measles).

The media and policymakers seem to have accepted that we will depend on herd immunity to defeat COVID-19. If we had a vaccine, everything would be different. But since a vaccine is not available, we must wait for enough people to be exposed and develop immunity.

In the meantime, we are being told to quarantine as much as possible so the medical system can deal with the many people who become infected. Simple, right? Unfortunately, it’s more complicated than this.

What the media and policymakers are not telling us is that the longer we delay the development of herd immunity, the more elderly or high-risk people will become infected and die, even if we were to maintain the quarantine indefinitely. Why is this the case?

The reason is that only young and healthy people contribute to herd immunity. Elderly and medically ill people generally do not contribute to herd immunity because their immune systems are not strong enough to develop an immune response.

This is not new or breaking science. To illustrate what happens when you don’t have herd immunity, look no further than the outbreaks we’ve had in areas where that immunity has dipped below the necessary levels.

In 2019, there was a massive outbreak of the measles in New York City for that reason. In 2014, a measles outbreak in Disneyland sent the number of cases to a 20-year high. Without herd immunity, where enough people have had the disease to avoid driving major outbreaks, future spikes will likely be much bigger.

Indeed, the Imperial College modeling says as much: “Once interventions are relaxed (in the example in Figure 3, from September onwards), infections begin to rise, resulting in a predicted larger peak epidemic later in the year: The more successful a strategy is at temporary suppression, the larger the later epidemic is predicted to be in the absence of vaccination, due to lesser build-up of herd immunity.”

Importantly, in this report, the Imperial College COVID-19 Response Team’s partial quarantine did not include isolating high-risk individuals or those infected (!) from their households, which would be critical for a partial quarantine to work. In fact, in their models, the elderly and medically ill people had more contact with everyone in their household (i.e., except in their one scenario in which only cases are quarantined, which is not an adequate strategy by itself). This would greatly bias their findings in favor of a full quarantine.

Therefore, if we stop the quarantine for all low-risk people now, herd immunity would develop more quickly. If we also were to keep the elderly and high-risk people isolated from everyone else during this time, including their own family members (i.e., a partial quarantine), we would save countless lives, while also decreasing the stress on the medical system.

This strategy would also limit the stress on the medical system caused by the fear and panic induced by the full quarantine, a variable that has not been considered in most models and to which any physician on the frontlines can attest. And there would be limited impact on the economy.

Furthermore, limiting isolation to only high-risk individuals and cases would be much more practical and likely to work since the more people need to be quarantined, the less effective is the quarantine. It would also still relieve much of the stress on the medical system since most of the severe outcomes occur in the elderly, according to the Centers for Disease Control.

A partial quarantine would still cause some initial stress on the medical system since the overall number of young or healthy individuals who would contract COVID-19 will not change with either a full or partial quarantine. The vast majority of these cases would be mild, however. Therefore, there may still be a slightly higher use of the medical system up front if we move to a partial quarantine as described herein. This could also lead to some deaths.

Herein lies the dilemma, or Sophie’s choice, of dealing with COVID-19. A full quarantine will result in the deaths of more elderly and medically ill people because more of them will become infected. A partial quarantine would likely result in a greater number of mild infections in young and healthy individuals upfront (but not total).

How many more elderly or medically ill people will die due to a full quarantine? It is hard to say, but a conservative estimate would be 5-10 times the number of young and healthy people who may die from a partial quarantine, based on fatality rates published by the CDC.

Fortunately, I am not responsible for making policy.

The author is an academic physician and researcher at an Ivy League institution in New York City.