If you want to stop Donald Trump from making unilateral decisions regarding war and peace, then stop letting all presidents make unilateral decisions about war and peace. It’s really quite simple. Trump can abruptly pull back U.S. troops from northern Syria because Congress, having abdicated its foreign policy responsibilities long ago, has no leverage to stop him.

When Congress passed the War Powers Resolution as the Vietnam War was winding down, it gave presidents the power to send troops abroad for 60 days in response to any “national emergency created by attack upon the United States, its territories or possessions, or its armed forces.” If the president failed to gain congressional support for the deployment, he would have another 30 days to pull back troops.

Congress is the institution vested with the power to declare wars, to debate where we send troops, and decide which conflicts are funded. Presidents have been ignoring this arrangement, abuse authorizations for the use of military force (AUMFs), and imbue themselves with the power to engage in conflicts wherever they like, without any coherent endgame, and without any buy-in from Congress.

Congress, in turn, has shown no interest in genuinely challenging executive power, because its members are far more concerned with political self-preservation. Ignoring abuse shields them from tough choices and ensuing criticism—even as they use war as a partisan cudgel.

Even if you don’t believe all these conflicts rise to an Article I declaration, and I don’t, the more accountability there is in foreign entanglements the better. Right now we have little genuine debate or consensus building—in a nation that already exhibits exceptionally little interest in foreign policy—regarding the deployment of our troops, almost always in perpetuity, around the world.

It’s a bipartisan problem. Barack Obama, whose political star rose due to his opposition to the Iraq war, was perhaps our worst offender, circumventing Congress and relying on a decade-old AUMF, which he invoked 19 times during his presidency, to justify a half-hearted intervention against ISIS (not al-Qaeda) in Syria (not Afghanistan.)

Trump could bomb Iran tomorrow, use Obama’s reasoning, and have a far stronger legal defense for his actions.

It was also Obama who joined Europeans in the failed intervention in Libya, where he worked under NATO goals rather than the United States law. There was hardly a peep from Democrats fretting over the corrosion of the Constitution.

Republicans too were given ample chance to sign-off on Syrian intervention in 2013 when Obama, fully aware of congressional aversion to accountability, asked for a new AUMF to get out of bombing Assad. It would have been a great time for senators to dictate long-term goals in Syria. It’s not too late. If they believe Trump’s strategy is wrong, they can still force his hand by explaining the mission with a new AUMF. Let’s see if voters agree.

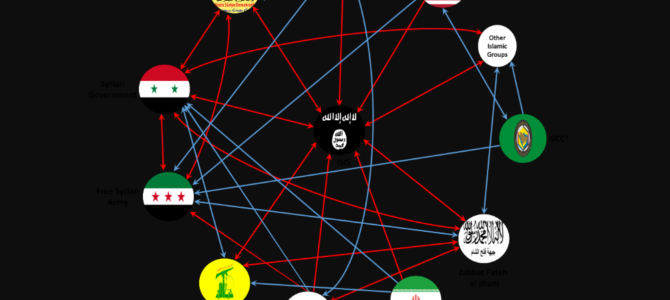

Right now, I imagine only a sliver of Americans fully understand the situation in Syria. I’m definitely not one of them. Yes, Trump’s haphazard abandonment of Syrian Kurds and empowering of Turkey seems like a bad idea for a bunch of reasons. I’m hawkish about destroying the remnants of JV-team ISIS and sympathetic towards the idea of protecting civilians from Assad’s chemical attacks and shielding the Kurds from Turkish aggression. But now we’re talking about an open-ended military commitment that keeps evolving. And anyone who claims with any certitude to know how these events will shake out is just lying to you.

The only thing we can be certain of is that there few good options in the Syria mess, and that includes our allies. Although the Kurds have endured much as a people, and deserve our support, the Kurdish PKK, our allies in northern Syria, aren’t chaste freedom fighters but Maoists with ties to terrorist organizations.

Or, in other words, we face few good options mired in perhaps the most volatile situation in the world. Under these conditions, our foreign policy shouldn’t be driven by the arbitrary “great and unmatched wisdom” of any single person. This brand of unilateral power was problematic when the well-mannered Obama sold out Syria to coddle the Iranian terror state, and it’s problematic when an impulsive Trump acquiesces to the wishes of Erdogan. (Although Washington only seems to freak out when the word “withdrawal” is mentioned.)

Whoever is president, the founders clearly foresaw Congress taking far more responsibility for conflicts we enter. So who knows, maybe next intervention it will?