Angela Kennecke is a popular reporter for a television news station in my hometown of Sioux Falls, South Dakota. Each weeknight, Kennecke is at the anchor desk for KELO, a CBS affiliate, and has been there as long as I can remember. For many people in the “Sioux Empire,” Kennecke’s work on television is a normal part of the day, and they can count on her to tell them how it is.

But Kennecke’s objectivity was shaken in May 2018, when her 21-year-old daughter, Emily, was found dead after overdosing on heroin that had been laced with the opioid fentanyl. This tragedy, which made national news, deeply affected Kennecke and the Sioux Falls community. Now, almost a year since Emily’s death, Kennecke has become South Dakota’s leading reporter on the opioid crisis.

In 2017, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) counted 47,600 opioid-related deaths, three-quarters of which involved heroin or “synthetic opioids other than methadone,” a category that consists mainly of fentanyl or its analogs. In 2011, 2,666 deaths involved drugs in that category; by 2017 the number had increased to 28,466, or 60 percent of opioid-related deaths.

Fentanyl in the medical setting is the narcotic drug most commonly administered during surgery. Outside the surgical room, it is primarily prescribed by doctors in the hospital to palliative care patients due to its high potency, which is 50 to 100 times greater than that of morphine. Unfortunately, fentanyl is also dirt cheap for black-market drug dealers to import from China and Mexico. In recent years, traffickers have increasingly turned to fentanyl as a heroin booster and substitute.

The Rise of Black Market Fentanyl

Although opioid-related deaths are driven mainly by heroin and black-market fentanyl, you would not know that from most of the press coverage, which emphasizes pain medication prescribed to patients who become addicted, overdose, and die. This narrative is “fake news.”

Just 30 percent of opioid-related deaths in 2017 involved commonly prescribed pain pills, and most of those cases also involved other drugs. People who die after taking these drugs typically did not become addicted in the course of medical treatment. They tend to be polydrug users with histories of substance abuse and psychological problems.

Contrary to what you may have read or see on TV, addiction is rare among people who take opioids for pain. In a 2018 study of about 569,000 patients who received opioids after surgery, for example, just 1 percent of their medical records included diagnostic codes related to “opioid misuse.” According to federal survey data, “pain reliever use disorder” occurs in 2 percent of Americans who take prescription opioids each year, including non-medical users as well as bona fide patients.

“The current battle against fentanyl as a street drug has little or nothing to do with American medical practice,” writes Harvard-trained anesthesiologist Richard Novak. “Most of the fentanyl found on the streets is not diverted from hospitals, but rather is sourced from China and Mexico.”

Yet, politicians, law enforcement agencies, anti-drug ad campaigns, movies, and TV shows still put pain treatment at the center of the “opioid crisis.” Kennecke’s reporting has helped perpetuate this false narrative. In a 50-minute news special that aired last December, for instance, representatives of the two largest South Dakotan hospitals brag about cutting opioid prescriptions by a whopping 38 percent. Kennecke asks no questions and shows no skepticism.

While fentanyl is mentioned as a cause of the crisis, prescription analgesics gets much of the blame. A viewer only needs to see the opening image of a black background covered in a waterfall of pills to understand the correlation being made. In her news reports and work for her opioid-addiction charity, Emily’s Hope, Kennecke frequently refers to prescription opioids while talking about deaths caused mostly by fentanyl and heroin.

To be fair, her reporting and charity work are done with good intent, and Kennecke is far from alone in reporting this narrative. You can almost count on two hands the number of journalists in the country reporting on this issue responsibly. But this kind of thing—where someone pushes a specific narrative for a cause without regard to the full context and facts of a story—isn’t journalism, it’s activism.

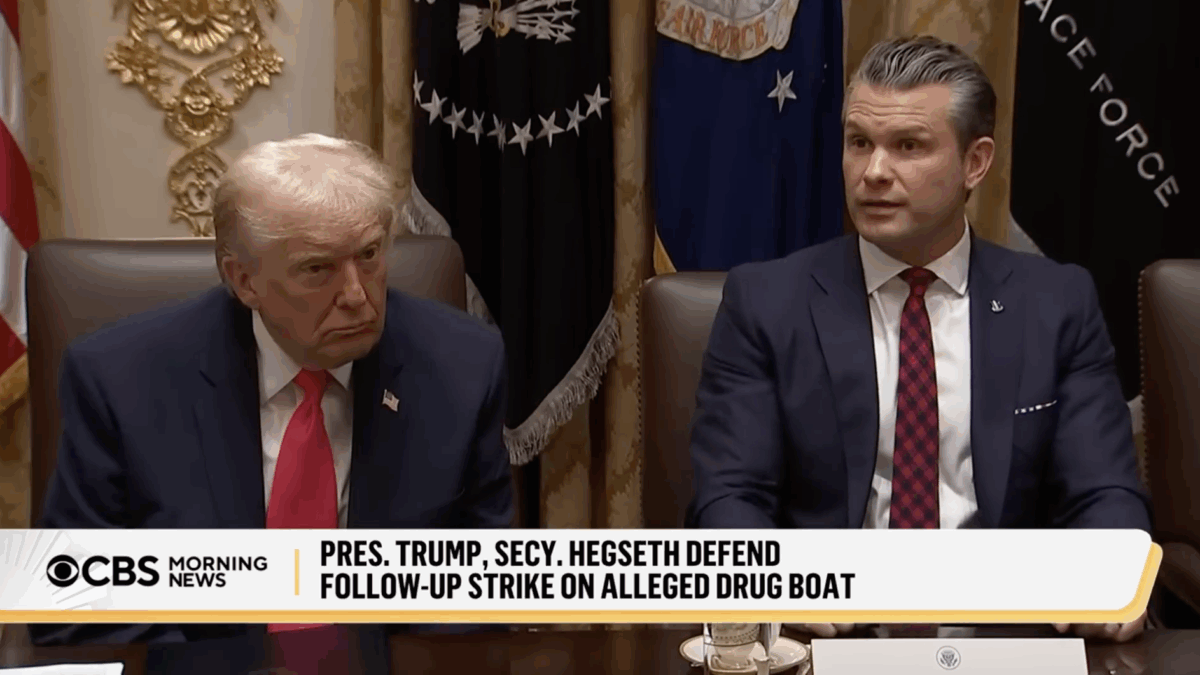

No one can blame Kennecke, Eric Bolling (a national conservative personality whose son died from a fentanyl overdose in 2017), or any other journalist whose life is affected by a fentanyl death for getting emotional. It is understandable that they feel as strongly as they do. But reporting one-sided and biased information is unethical because their reporting is influential.

For example, Bolling reportedly has President Trump’s ear and helped influence an anti-opioid bill package that Congress passed last year. Activism like this comes with a heavy price.

Cracking Down in the Wrong Areas

Thirty-three states have now created laws that severely restrict opioid prescriptions in response to the hysteria. Most of these laws put hard day limits on prescribers. In Florida, for example, they impose a three-day limit on any prescription opioid for acute pain. The combination of these laws, plus overactive Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) agents, has made pain specialists scarce in states such as Montana and Tennessee.

Due to the media hysteria which in turn inspires political hysteria, it is now harder than ever to get an opioid prescription for those in chronic pain, even though there is currently no equivalent medical treatment to replace the prescription opioids used by 18 million Americans for long-term pain. In 2017, a New England Journal of Medicine study found, the number of doctors who prescribed opioids at all fell by 29 percent. That same journal in a more recent study found a decline of 54 percent in prescription opioids by doctors for first-time-opioid patients between 2012 and 2017.

A nationwide survey of almost 4,000 pain patients by Dr. Terri Lewis found that 56 percent reported either disruption in pain treatment or outright abandonment by their once trusted doctors.

So awful is the reaction against chronic pain patients that 300 drug policy, addiction, and pain treatment experts, including three former White House drug czars, recently urged the CDC to clarify its 2016 opioid prescription guidelines, which have been widely interpreted as imposing arbitrary limits on average daily doses. Last November, the American Medical Association approved a resolution noting that guidelines had been read “by pharmacists, health insurers, pharmacy benefit managers, legislatures, and governmental and private regulatory bodies in ways that prevent or limit access to opioid analgesia.”

While the news media aren’t to blame for the backlash against doctors and their chronic pain patients, they are guilty of sustaining the moral panic underlying it—a panic that is causing many needless deaths. Just go to any chronic pain patient forum, social media group, or even the federal government’s regulatory website to read the thousands of stories of quality-of-life reductions and suicide plans.

Kelly Goricki, a mother of four, offered this account on Chronic Pain Reddit:

It pisses me off when I get treated like a drug-seeking junkie by doctors who can CLEARLY see my well-documented injuries in my medical files. It pisses me off when my doctor, who doesn’t have chronic pain and has watched my injuries worsen dramatically over the last decade+ tells me I/my injuries ‘shouldn’t hurt that bad/aren’t that bad,’ as she watches my physical decline and takes away pain meds that allowed me to care for myself, my home, and my family, just so she ‘doesn’t have to deal with the paperwork.’ It pisses me off I’m treated like a junkie bad mother because someone finds out I take pain medication. It pisses me off that people assume the same meds I have been prescribed for (years) ….. make me high, or that I abuse them to get high.

An anonymous commentator had this to say on the government website regulations.gov:

I have fibromyalgia, arthritis, depression and diabetes. About 2 years ago my physician decided to take all of (his) patients off of pain meds. … The pain level is very extreme and it is 24/7 chronic pain. I can not function with this pain at a level that I could full time. I live by myself and can no longer support myself. I feel that eventually suicide may be my only option. I never abused my meds and I was able to function.

All this misery for this patient, Goricki, and an untold number of other patients is happening because the media and the CDC have made their physicians’ jobs impossible.

Desperation for Chronic Pain Patients?

Many of these patients used their prescriptions responsibly for decades, but they are now being pushed into trying dangerous surgical interventions or desperately buying drugs off the street. Reporters like Kennecke are helping to push chronic pain patients past their breaking point. It’s a pointless sacrifice, since opioid-related deaths have continued to rise even as prescriptions of pain medication have fallen dramatically.

As someone who is disabled and suffering from intractable pain, I know this problem keenly. For more than a year, I have lived without a prescription of low-dose oxycodone I responsibly used for almost nine years.

While not a perfect treatment for my pain, oxycodone did allow me enough function to survive. While on it, I attended college, served a mission, obtained my bachelor’s and master’s degrees, and ran for school board twice. All that was taken away from me a year ago by a doctor who didn’t want to deal with the hassle that now comes with opioid prescriptions.

Reporters like Kennecke are doing what they think is right. The deaths caused by fentanyl are real and atrocious. But what she and too many of our leaders are doing by associating prescription opioids with fentanyl deaths is unethical and inaccurate. And the deaths of innocent pain patients will be the price of it. Journalists must ask themselves: Does our misreporting have a cost?