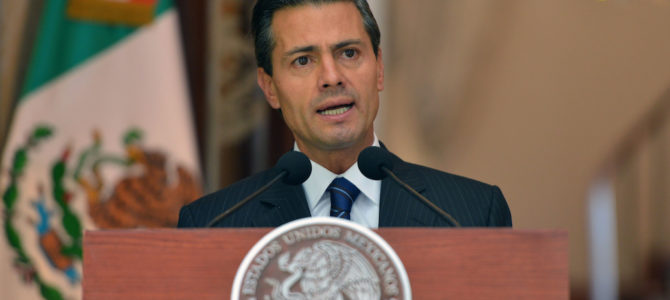

A witness in the ongoing trial of infamous Mexican drug cartel kingpin Joaquín Guzmán Loera, a.k.a. “El Chapo,” testified Tuesday that former Mexican president Enrique Peña Nieto took a $100 million bribe from Guzmán.

The witness, Alex Cifuentes Villa, is a former Colombian drug lord who worked closely with Guzmán from 2007 to 2013. His bombshell testimony comes amid a trial that has revealed corruption at almost every level of the Mexican government.

According to The New York Times, one of Guzmán’s lawyers, Jeffrey Lichtman, asked Cifuentes during cross-examination, “Mr. Guzmán paid a bribe of $100 million to President Peña Nieto?” “Yes,” responded Cifuentes.

Later, Cifuentes said Peña Nieto is the one who first reached out to Guzmán, asking for $250 million in exchange for allowing him to come out of hiding. Guzmán offered $100 million instead.

MORE on EPN:

Cifuentes said that EPN reached out to Chapo first, asking for $250 million. Chapo offered EPN $100 million.

"The message was that Mr. Guzman didn't have to stay in hiding?" Chapo's lawyer asked.

"Yes," Cifuentes said, "that very thing is what Joaquin said to me."— Alan Feuer (@alanfeuer) January 15, 2019

When the trial began back in November, Lichtman alluded to high-level bribes and payoffs while outlining an overall defense that alleged Guzmán was framed by his partner, Ismael Zambada García, in league with corrupt American D.E.A. agents and top officials in the Mexican government, including two presidents.

Peña Nieto denied taking bribes at the time. Later the judge in the case, Brian M. Cogan, forbade testimony from Jesus Zambada García, Ismael Zambada’s brother, who reportedly would have testified that two Mexican presidents took bribes from the Sinaloa drug cartel.

He did, however, testify that he had bribed Mexico’s top law-enforcement official under President Felipe Calderón, twice handing off briefcases stuffed with $3 million in cash to Genaro García Luna, who was in charge of the Federal Investigation Agency, Mexico’s federal police force equivalent of the F.B.I., and was later appointed secretary for public security.

If Cifuentes’s testimony about Peña Nieto is true, it suggests that drug cartels in Mexico have infiltrated the highest levels of government, and have been doing so for years. The question of deep and widespread corruption in Mexico is nothing new—Peña Nieto’s administration was so badly plagued by corruption scandals that it sought to shield federal officials from a corruption probe in the months before Peña Nieto left office. But corruption in Mexico has taken on new significance amid the humanitarian crisis on the U.S.-Mexico border.

Record numbers of Central American families and minors are attempting to cross into the United States and claim asylum at a time when criminal networks in Mexico have largely seized control of the border in their efforts to commercialize migration into the United States. Although precise amounts are hard to pin down, cartels and smuggling networks are estimated to earn hundreds of millions of dollars annually from human smuggling.

President Trump says there’s a crisis at the border, and in a sense he’s right. But the crisis is not that migrants are crossing into the country illegally. That’s been happening for a long time (and overall numbers of illegal immigrants are currently at historic lows).

The crisis is the deep and endemic corruption in Mexico and Central America, where powerful cartels have a vested interest in controlling and continuing illegal immigration and governments are powerless to stop them—in part, because officials in those countries are in on it. If it turns out corruption in Mexico reaches to the very top, then we have a lot worse problems to deal with south of the border than migrant families seeking asylum.