We need to talk about hunting, which for some reason has been in the news lately. Specifically, we need to talk about the difference between trophy hunting and hunting for sport or subsistence, and why those differences matter.

Vegans and environmentalists will decry all hunting as barbaric and inhumane, but some recent stories illustrate why trophy hunting is fundamentally different from, and inferior to, hunting for almost any other reason—and why it should be beneath us as human beings.

First, there was the news that Prince Harry will skip the royal family’s traditional Boxing Day pheasant shoot this year at the behest of his animal-rights activist wife, Meghan Markle, who reportedly condemns the shooting of “defenseless animals” and has forbidden the prince from going on the hunt.

Then there was the judge in Missouri who earlier this month sentenced a man to a year in jail for poaching hundreds of deer, mostly trophy bucks taken at night for their heads, leaving the bodies to rot. The judge added an unusual twist to the man’s sentence: he is required to watch “Bambi” once a month while behind bars.

Then last week, a trophy hunter shot and killed a wolf named “Spitfire,” apparently beloved by wolf enthusiasts and biologists, after it wandered outside Yellowstone National Park, sparking outrage.

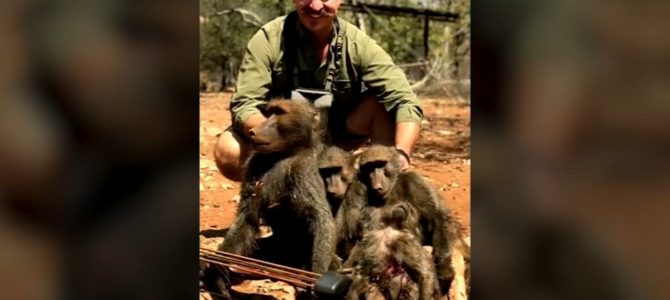

All of this calls to mind a story from this fall, when Idaho Fish and Game Commissioner Blake Fischer was forced to resign after sharing photos of a trophy hunting trip in Africa with friends and colleagues, including one particularly macabre photo of a smiling Fischer with a “family of baboons” he killed with a recurve bow.

Now, as a red-blooded American and an ardent supporter of the Revolutionary War, I don’t really care what Prince Harry does, much less what his wife the duchess of Sussex thinks about hunting. But of all the above stories, his is the only one that should elicit sympathy for the simple reason that the pheasants shot by the royal family will eventually be eaten.

One might protest that the House of Windsor doesn’t need to shoot pheasants to feed the queen (although she does eat pheasant). I admit, British royals in their tweeds shooting pheasants on some vast estate doesn’t naturally elicit Americans’ sympathy. But that’s all the more reason to use their case to illustrate the crucial difference at issue here.

Killing For Fun, Or a Wall Decoration, Is Ignoble and Small

So what’s the distinction between trophy hunting and hunting for sport? Obviously, the entire point of trophy hunting is sport (and to bag a trophy to hang on the wall). But not all sport hunting is trophy hunting. Consider the royals and their pheasants. What’s now a rather elaborate and indulgent aristocratic tradition began simply as a way to get food. Today, it’s both sport and subsistence—the pheasants and grouse killed in these hunts are generally donated to charity and used to feed the poor.

That combination of sport and subsistence is not unlike most hunting in America. I grew up in Alaska, where most people hunt something at some point in the year, mostly for food but also for recreation. As kids, my brothers and I had a hillbilly version of the royals’ pheasant hunt, which involved crashing through the woods to scare up and shoot as many spruce grouse as we could find. We always ate them, of course, but it was (and is) great fun to hunt them.

It’s the same for large game like moose and bear. Alaskans go to great lengths to find and shoot these animals, sometimes spending weeks in remote mountains and forests. If they’re successful, they might mount a moose rack or hang a bear hide on the wall, but the animals are almost always eaten. For moose in particular, subsistence is the primary reason for the hunt. For a family, bagging a moose can provide a year’s worth of red meat at a fraction of what it would cost to buy beef in the grocery store.

However, if the primary reason is merely to mount a rack or hang a hide, it would be difficult to justify taking these animals. Killing a wild animal for fun is no less ignoble than killing a pigeon or a feral cat for fun. It belies an imbalanced view of the world, and one’s self, and indulges a lust for violence that’s unhealthy. For Christians in particular, trophy hunting shows a lack of reverence and respect for creation, and it undermines our God-given role as stewards of the earth.

Note what I’m not saying. I’m not saying trophy hunting is wrong because wild animals are “defenseless” (they’re not). Nor am I saying it’s wrong because people shouldn’t eat animals (they should, animals are delicious). I’m saying that there’s something shameful and small about killing a wild animal just to mount its head on your wall.

Conservation Doesn’t Require Trophy Hunting

But, some will say, there are other good reasons for trophy hunting—reasons more noble than simply killing for fun, or to decorate a wall. Conservation, for instance. If no one hunted grizzly bears or wolves for sport, we would have no reason to maintain their populations and they would eventually go extinct. This is a version of Teddy Roosevelt’s argument for hunting:

In a civilized and cultivated country wild animals only continue to exist at all when preserved by sportsmen. The excellent people who protest against all hunting, and consider sportsmen as enemies of wild life, are ignorant of the fact that in reality the genuine sportsman is by all odds the most important factor in keeping the larger and more valuable wild creatures from total extermination.

Although there’s a certain logic to this, it made more sense when Roosevelt said it in 1905 than it does today. Back then, there were far fewer protections for wildlife and wilderness, and therefore far greater risk that wild animals would be killed off as the country developed. Indeed, the black bear, gray wolf, and bobcat were once native to the Midwest but were wiped out from hunting and agriculture in the 19th century. Thanks to a century of conservation and wildlife management, some of those species are now making a comeback in the Midwest, as are other apex predators that were once considered pests to be exterminated.

Indeed, it was Roosevelt’s establishment of national forests, parks, and preserves that saved many North American species from extinction. We now know that wild animals and their habitats can be preserved and managed even as the country continues to grow, and that one need not preserve bobcats or wolves merely to shoot them for their hides.

It’s easy to wave a hand at all this and dismiss it as hair-splitting. But a decent respect for nature, including man’s place as steward of it, obliges us to think carefully about conservation and hunting, and to make distinctions between wanton killing and legitimate sport and subsistence. Maybe the duchess of Sussex refuses make those distinctions, but every other American should.