The bright side of working at an urban high school is that, while one is more likely to be killed in a targeted act of violence, one is less afraid of being killed in a random mass shooting. I don’t say this without acknowledging the absurdity of such a statement, but it’s fairly obvious to those of us who operate daily within such places.

While my school continues to improve academically and on-campus gang violence recedes due to gentrification, there are still enough students on campus carrying guns that if someone did start randomly shooting up the school, the homeboys would likely bust back.

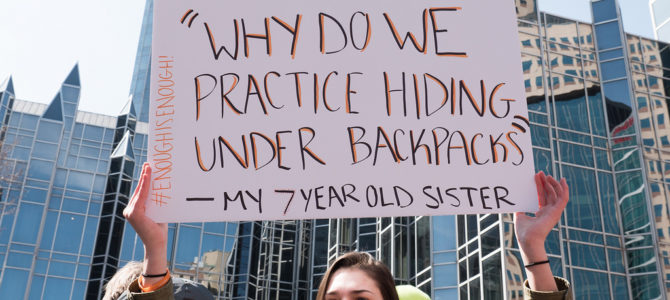

Perhaps this is why such a low percentage of my students participated in the walkout on March 14, a day the youth branch of the Women’s March movement selected to honor the 17 students and staff murdered in the Parkland school shooting. Perhaps my students’ general disinterest was a direct result of my general disinterest. Perhaps they were so excited to attend my class that they decided not to leave, although regular attendance records might dispute this. Or perhaps Socrates cured them of a toxic cultural psychosis.

No One Marched When Lamar Was Murdered

To understand this disorder, let first me make a confession. I don’t know the names of the 17 victims in Parkland, Florida. I don’t know their addresses, families, or favorite foods. Given a map of Florida, I would be challenged to even point to Parkland’s general location. Everglades, Panhandle, Gulf-side, South Beach—Parkland could be anywhere and, in my mind, is nowhere at all.

That’s partly why my apathy was so strong. Had it been a local student, one of our own, I would have gone, as I did last year when one of my students was murdered. On a Monday night, while holding a Bible study in my home, I received a phone call from Oscar. Through tears, he confided in me, “They killed Lamar, coach.” After praying with the group for his family, the community, and the cessation of future violence, I went to the scene.

Prayers were said, along with curses. Clenched fists mirrored clenched teeth. Vigils were held at candlelight, a moment of silence over the school’s PA system, and a funeral service so full that people stood in the aisles along the walls. Our community echoed with the grief.

But no one marched. No national news outlet carried our disaster to distant communities. There were no balloons held up at middle schools in Amherst, Massachusetts or Easton, Pennsylvania. The children of Chevy Chase, Maryland did not spill into the street demanding an end to the violence in Hayward, California.

This isn’t to blame them. It was a local grief over a local loss. To be honest, it did not register even one town over. But it was our loss, and we felt it and owned it as such.

What My Students Know about Violence

Let me make a second confession: I’m fairly certain none of my students nor most students around the country know the Parkland victims’ names, either. They certainly don’t know their parents or families, the names of the streets they live on, the particularity of their roads, or what the weather is like there this time of year. This did not stop great numbers of them from leaving their classes and marching. Those very actions of marching, protest, speech, and memorial seem to be from a place of care and concern borne of personal relationship and knowledge.

Yet knowledge of the very things most significant in the daily lives of each of my students seems most lacking. Such knowledge could help them where they are. It could change their communities, lives, and streets. This kind is knowledge of the local.

So that day in class, I questioned them. I asked if they knew the names of their school board members or city councilmen. I received blank stares and raised shoulders. About half knew their neighbors’ names, and half of that group knew only that about their neighbors.

In a discussion about why certain neighborhoods in our community were so violent and crime-ridden while others only blocks away were relatively safe, it was clear they didn’t know where local jurisdictions began or ended. When I asked where the money came from to build the new elementary school up the hill, where some of their own brothers and sisters attended. They had no idea.

It was like the workings of their own community were some divine miracle and I was the prophet pulling back the curtain that separates heaven from earth. But isn’t that experience of the mystical what democracy is supposed to avoid? All our committees and elected officials operate in transparency. Meeting notes are almost always available online, and most meetings remain open to the public. Ballots have common language with multiple translations and candidates’ voting records are public.

Why Are We So Disconnected From Next Door?

Apologists might argue that “People in poor, urban environments have less time and other resources to find those public records, and that explains their ignorance.” But having taught for seven years in a more middle-class community, I know absenteeism from and ignorance of the daily grind of local governance are not limited to poor, urban communities. Students all over, from San Francisco to Sioux Falls, are far more concerned with our tweeter in chief’s latest verbal hemorrhaging than with local school budget cuts.

This begs the question: What forces are encouraging such paradox? How have we created a society where students are encouraged to concern themselves with far distant events and civic concerns so far removed from the pothole-lined road they drive down or the homeless stretched out beside them as they walk to school? Why is their attention focused on a national shooting while a classmate’s murder remains unsolved one year later?

We could put together a “study,” perhaps do some polling. A Pew Research grant could be written or perhaps CNN could put together a student panel, but I think we would still fail to find the fundamental reasons behind this. However, answers to these questions about the loss of a sense of local civic connectedness might be found in the ancient wisdom of Socrates in his dialogue, “Gorgias.”

The Art of Manipulating the Ignorant

In “Gorgias,” Socrates faces the eponymous rhetorician, who describes his art that “gives to men the freedom in their own persons, and to individuals the power of ruling over others in their several states.” Through speech and the ability to convince with language, Gorgias says, the rhetorician becomes the master of all who “persuades the judges in the courts, or the citizens in the assembly, or at any other political meeting.” This “art,” as Gorgias calls it, is of tremendous value to those who wish to win political office or be considered “great.”

Socrates asks if such a man could ever be considered truly great. Wouldn’t this man be able to convince people even against the advice of those who truly know? This Gorgias considers a boon: “Is not this a great comfort? – Not to have learned the other arts, but the art of rhetoric only, and yet to be in no way inferior to the professors of them?”

See, for Gorgias, rhetoric allows its master to control others without having to be a master of anything. Such control can even be achieved in the face of the truth, for example, that certain rights should be taken away or certain procedures undergone for the sake of some greater purpose.

Socrates’ response is scathing: “Does he really know anything of what is good and evil, just or unjust; or has he only a way with the ignorant of persuading them that he, not knowing, is to be esteemed to know more than someone who knows?” The rhetorician’s wiles and tricks cannot work against the knowledgeable. He cannot fool the doctor or the carpenter about their craft. He cannot convince the stone-mason which stone is best nor the philosopher about his philosophy. For his rhetoric to work, his listeners must remain ignorant.

Keeping People Ignorant Keeps Them Impotent

This identifies the purpose behind my students’ ignorance. It is far easier to act well or justly when one knows one’s neighbors and acts locally. I know better what is good for the person next door than what is good for the person a continent away. In a similar way, it’s easier to judge good and evil action when engaged with a single person in one’s own household than when making laws that blanket hundreds of millions. So it would make sense that if those in power wanted people to act justly they would encourage them to know their neighbors and understand the workings of their city.

Instead, the powerful, seeking to retain their power, encourage a focus on the distant and unchangeable so the people remain in ignorance. Then those who know least, who aren’t even mature enough to vote, become the “ones we must follow.”

For further evidence that rhetoricians have ascended to our social heights, look no further than the 2008 economic collapse. In cities around the country, especially along the coasts, professional “wizards” who had spent years assuring the ignorant masses that everything was fine were blindsided by the greatest economic collapse in 80 years. One hundred-year-old financial kingdoms melted, and millions plummeted into poverty.

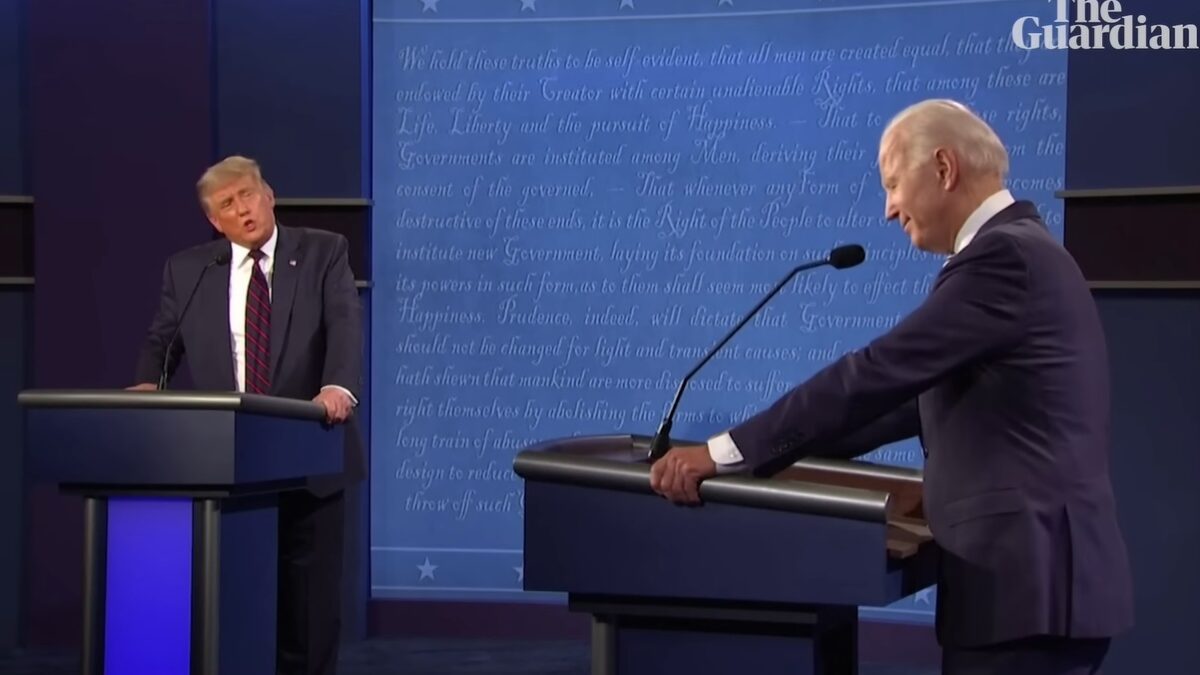

This is a way to make sense of how we arrived at a reality TV star presidency. It’s also a way to understand how, in just a few short years, five black robed mages swept aside what society has generally agreed on since time began. Who is to say what justice looks like with such a distant lens?

If we indeed seek to do what is good and just, like Socrates argues we should, perhaps we should turn our attention to the pothole and the broken street light, the neighbor whose shouting can be heard from indoors, the school board meeting held on Wednesdays, or the flowers girding the altar. When we have perfected that, perhaps then we will be ready to look further.