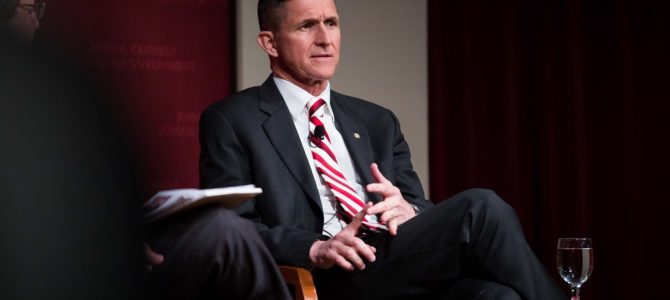

On Friday, news broke that text messages now establish that Peter Strzok, the disgraced Federal Bureau of Investigation agent involved in investigating Michael Flynn, was friends with Rudolph Contreras, the federal judge originally assigned to handle Flynn’s criminal case.

Less than a week after Flynn pled guilty before Contreras, the criminal case was reassigned to Judge Emmet Sullivan. Contreras’ recusal came without explanation, leaving observers to assume Contreras’ service on the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court (FISC) created a conflict that necessitated recusal.

If so, however, why had Contreras been involved at all? Shouldn’t he have immediately recused himself? The recently revealed text messages provide an answer that both vindicates Contreras and indicts the FBI and Department of Justice (DOJ).

Contreras Might Not Have Known Strzok Was Involved

First the backdrop: On December 1, 2017, Flynn appeared before Contreras in a federal district court in Washington DC and pled guilty to making false statements to the FBI. In pleading guilty, Flynn admitted he made false statements to FBI agents during a January 24, 2017, interview. One of those agents was Strzok.

However, Flynn’s “Statement of the Offense,” which detailed the factual basis for his guilty plea, did not name Strzok. Rather, the statement referred only to “agents from the FBI.” Similarly, in charging Flynn, the information—which initiates a criminal prosecution without a grand jury indictment—issued by Special Counsel Robert Mueller’s office did not name Strzok but referenced “agents of the Federal Bureau of Investigation.” Thus, when Contreras accepted Flynn’s guilty plea on December 1, 2017, the charging documents and Flynn’s plea agreement had not disclosed Strzok’s involvement in the case.

The text messages between Strzok and the FBI attorney with whom he was allegedly having an extramarital affair, Lisa Page, also showed that Contreras had no reason to presume Flynn had interviewed Strzok or had detailed knowledge concerning the Flynn case. For instance, the Daily Caller reported that in one text message Strzok said “Contreras ‘generally’ knew what Strzok did for a living,” but “[n]ot the level or scope or area.” Strzok added that Contreras is “super thoughtful and rigorous about ethics and conflicts.”

It is possible, of course, that at the time Contreras presided over the Flynn case, he knew Strzok had interviewed Flynn or had been involved in the investigation of Trump’s former national security adviser. Only a few months earlier, a smattering of media outlets had reported that Strzok, who had served as chief of the FBI counterespionage section, had been removed from Mueller’s team.

But even assuming Contreras knew of Strzok’s role in the Flynn case, recusal was not necessary. Federal judges often know the attorneys and government agents appearing before them. Also, under the controlling law and Code of Conduct for United States Judges (Code of Conduct) recusal is not required even when there is a friendship or a social relationship involved.

When a Judge Should Recuse Himself

A judge’s obligation to recuse is governed by both federal statute and the Code of Conduct. The applicable federal statute, Section 455, provides that a judge must recuse from a proceeding “in which his impartiality might reasonably be questioned.”

Section 455 provides several examples to illustrate, including “[w]here he has a personal bias or prejudice concerning a party, or personal knowledge of disputed evidentiary facts concerning the proceedings,” or where a spouse or close family member is “likely to be a material witness in the proceedings” (emphasis added). Strzok, of course, was not a spouse or close family member of Contreras, and did not appear as a “material witness” in the proceeding, as Flynn had pled guilty.

Canon 3(C)(1) of the Code of Conduct mirrors this language. Additionally, Canon 2(A) of the Code of Conduct provides “[a] judge should respect and comply with the law and should act at all times in a manner that promotes public confidence in the integrity and impartiality of the judiciary.” And Canon 2(B) adds that “[a] judge should not allow family, social, political, financial, or other relationships to influence judicial conduct or judgment.”

The lay person—or even lawyer—not well acquainted with Section 455 or the Code of Conduct might believe Contreras’ “impartiality might reasonably be questioned,” given his friendship with Strzok, as revealed in the text messages disclosed on Friday. But, based on my six-plus years of experience researching diverse issues related to the Code of Conduct, such a view is inconsistent with a proper understanding of the federal statutory and ethical rules.

This conclusion finds support in Advisory Opinion 11 issued by the Committee on Codes of Conduct—a committee comprised of federal judges charged with providing guidance to judges and judicial staff concerning the controlling ethical rules. That advisory opinion considered whether a judge must recuse in a case in which a long-time friend served as an attorney.

The committee explained that a judge’s “impartiality might reasonably be questioned” in a case in which a “close friend whose relationship is like that of a close relative” appeared as an attorney. In contrast, recusal would not be required if the friend were merely one “within the wide circle of the judge’s friends.” The committee noted, though, that “[u]ltimately, the question is one that only the judge may answer.”

An Acquaintance or Friendship Doesn’t Demand Recusal

Even though Strzok did not appear as an attorney in Flynn’s case, this guidance proves helpful to understanding why the text messages vindicate Judge Contreras. The exchanges between Strzok and Page depict a friendship between Strzok and Contreras, but not a “close friendship,” akin to a “close relative” for which the committee would recommend recusal.

Strzok mentioned being friends with Contreras and of seeing him at a graduation party. Strzok also noted that while the judge knew about his work in general, Contreras didn’t know the level, scope, or types of cases on which he worked. These exchanges describe a friendship, within a wider circle of friends, which would not require recusal, as opposed to a “like family” type of relationship.

Further, while in retrospect recusal might seem the more appropriate option, it is important to recognize that a judge has both an obligation to recuse when appropriate and a duty not to recuse when recusal is unwarranted. As the committee on Codes of Conduct explained, “[u]nwarranted recusal may bring public disfavor to the bench and to the judge,” and shows a lack of “respect for the fulfillment of judicial duties,” and a disregard of the “proper concern for judicial colleagues.”

Why, then, did Contreras recuse a week after presiding over Flynn’s plea? There are two logical explanations. First, Contreras may not have known of Strzok’s involvement in the Flynn case until December 2, 2018—the day after Flynn pled guilty—when Strzok’s affair with Page and resulting removal from the Mueller investigation led the day’s news. Canon 3B(5) of the Code of Conduct requires a judge to “take appropriate action upon learning of reliable evidence indicating the likelihood that a judge’s conduct contravened this Code,” and Contreras may have judged recusal appropriate after learning of Strzok’s involvement.

Alternatively, Contreras may have seen no reason to recuse until Strzok’s conduct created concerns over the integrity of the investigation. At that point, Contreras may have believed recusal was the more prudent course of action to “promote[] public confidence in the integrity and impartiality of the judiciary,” or perhaps the chief judge of the D.C. District Court thought so and reassigned the case to Sullivan. But under either equally plausible scenario, Contreras’ conduct was consistent with the governing Code of Conduct.

This Puts the FBI and DOJ On the Hook

However, the text messages cast quite a different light on the conduct of the DOJ and the FBI’s lead agent and attorney (beyond their adulterous affair). The text messages reveal the couple’s desire to arrange for Page to meet Contreras—a cause so important to the duo that they were willing to arrange an intimate dinner party for six with, presumably, their respective spouses.

Page’s questions to Strzok further indicate she had an interest in Contreras because of his position on the FISC. That a high-level FBI lawyer involved in obtaining wiretap orders might seek to schmooze a federal judge sitting on the secret court that issues those warrants should shock the public’s conscience.

Equally appalling are the attempts to conceal Page and Strzok’s conduct from the congressional committees charged with oversight of the FBI and DOJ. As Mollie Hemingway reported on Friday, multiple congressional investigators told The Federalist the text messages between Page and Strzok about Contreras were deliberately hidden from Congress. Hemingway added that “in records provided by DOJ to Congress, the exchanges referencing Contreras, and plans to meet with him under the guise of a cocktail party, were completely redacted by federal law enforcement officials.”

The FBI and DOJ’s failed attempts to bury information from congressional oversight foretells of further revelations. The import of that likelihood far exceeds the news that Contreras was friends with Strzok. Flynn, who is currently awaiting Mueller’s compliance with the standing order from now-presiding Judge Sullivan directing the government to turn over “any evidence in its possession that is favorable to defendant and material either to defendant’s guilt or punishment,” likely agrees.