President Trump just nominated Jerome Powell, a lawyer and former investment banker, to chair the Federal Reserve. Powell’s nomination is seen as the safe choice. He is a Fed insider, appointed to the Federal Reserve Board of Governors by Barack Obama in 2012. Powell generally supports the administration’s deregulatory agenda for banks, but will stray little from current Fed Chair Janet Yellen’s monetary policy.

Aside from being the safe choice, Trump’s reasons for appointing Powell are quite clear. A more conservative Fed chair might seek to reduce monetary stimulus more quickly and move interest rates higher. A more conservative Fed chair might also seek to raise rates even if inflation remained low, or question the Fed’s inflation targeting framework altogether.

No modern president steeped in conventional wisdom wants to see interest rates rise too quickly on his or her watch. And Trump has repeatedly expressed his love for low interest rates. The conventional wisdom says low rates are always good for economic activity. As long as inflation remains low—a sign the economy is not overheating—rates can remain low too.

Status Quo Monetary Policy Hurts American Workers

This conventional wisdom is wrong, however, and Powell will likely continue the failed monetary status quo. This means subdued American economic growth, more debt, and slower real wage growth for Americans.

In the last 30 years, median workers’ real wages have been flat. Since the late 1990s, median real wages have declined. Tax policy, education, and regulation are important for real wage growth, but nothing affects the long-term trajectory of economic growth more than monetary policy.

Yes, low wage growth is partially due to demographics, more single-parent families, and women entering the workforce. But the data also shows flat median incomes since 2000, even when controlling for these other factors. This suggests another factor at play, especially in certain industries.

For example, manufacturing, construction, mining, transportation, and utilities workers have experienced particularly low wage growth since 1980. On the other hand, for professional and business services, finance, health, and education employees, pay growth has been steady. The monetary status quo lies behind much of this wage stagnation. To explain, let’s start with some history.

How We Got Into This Mess

Sending the pain of federal budget deficits to future generations. After Lyndon B. Johnson’s Great Society and Vietnam War spending, the United States started running federal budget deficits in the 1960s. In the face of pressure on the dollar’s peg with gold, Richard Nixon ended the dollar’s convertibility to a fixed amount of gold. This ushered in the era of fiat money.

The old Bretton Woods gold standard that Nixon abandoned, imperfect as it was, brought balance to global trade. When one country ran too high of a trade deficit, gold reserves would flow out and the cost of credit in that country would rise, leading to more production and less consumption, which would eventually bring the trade deficit to a surplus. Thus, a gold standard naturally balanced trade deficits.

In the era of fiat money, however, the U.S. dollar was now the world’s reserve currency, not gold. This meant that a country might be perfectly fine with selling America goods in return for our dollars. That’s exactly what happened when China was brought into the World Trade Organization. Mercantilist China was happy to sell us goods and receive paper dollars in return. China then hoarded the dollars, using them to buy U.S. assets—mostly U.S. government debt, also known as Treasurys—instead of goods produced in America.

Now, instead of U.S. rates rising due to trade deficits, they were pushed down even further, and our trade deficit never self-corrected. This is because when more investors want to buy Treasurys, the U.S. government can issue debt at a lower cost to taxpayers, also known as a lower yield or rate.

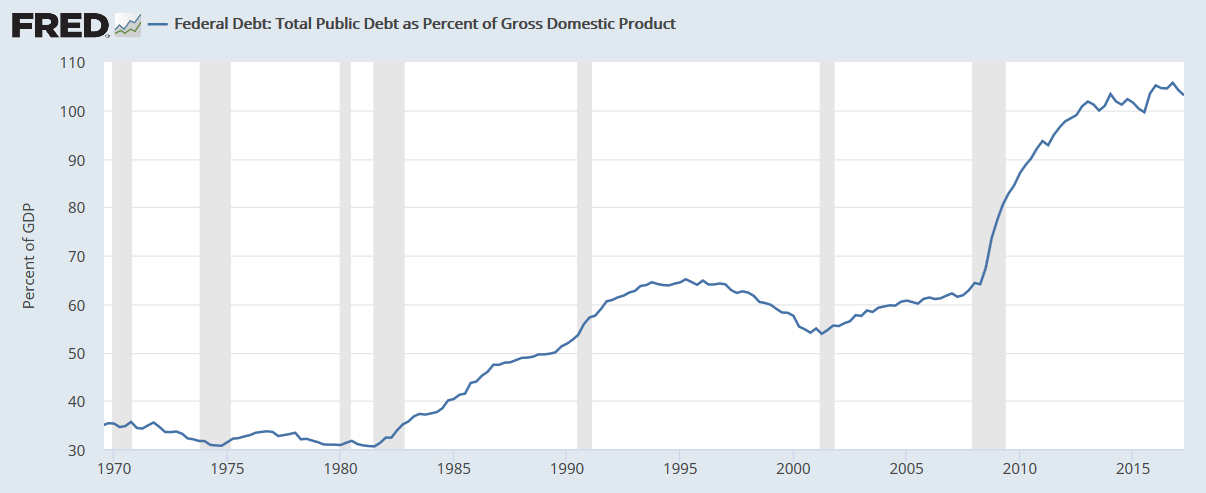

Over the last 30 years, government deficits also started to not matter to our government bond market. In the bygone halcyon days of the mid-twentieth century, government deficits and their crowding-out effect of higher private-sector borrowing costs prompted the business lobby to march up to Capitol Hill and demand government cut spending.

The statesmen of the day eagerly complied. Here’s what Dwight Eisenhower wrote to a friend: “I have always maintained one thing – that the annual Federal deficit must be eliminated before tax reduction can begin … So I spend my life trying to cut expenditures, balance the budget, and then get to the popular business of lowering taxes.”

Along came the Reagan revolution, however. Believing inflation would remain at the levels seen in the early 1980s, and worried about bracket creep, Reagan passed a supply-side tax cut without significantly cutting spending. But Paul Volcker, the Fed chair at the time, whipped inflation with high rates and Reagan’s 1981 tax cut and federal spending ended up being a lot bigger than expected in inflation-adjusted terms.

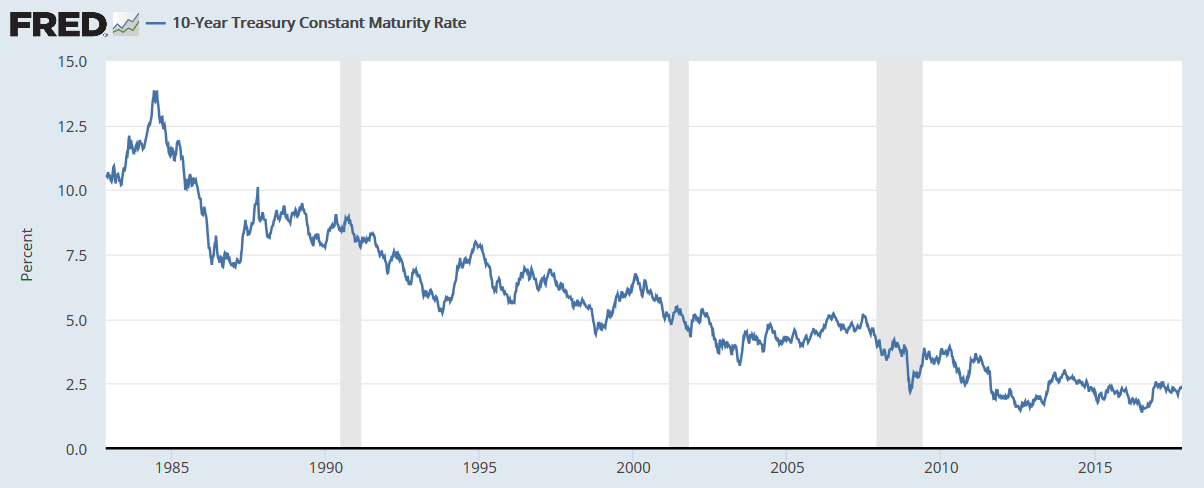

According to Reagan’s Office of Management and Budget Director at the time, David Stockman, the result wasn’t massive government revenues, but massive deficits. Between the start and finish of Reagan’s two terms, federal debt moved from $930 billion to $2.74 trillion, an addition of a whopping $1.8 trillion, or 200 percent more debt than all the Gipper’s predecessors combined had accumulated over 190 years. As a result of higher deficits, the 10-year Treasury yield (the government’s cost of borrowing) went parabolic. Between the start of 1987 and September of that year, the 10-year yield rose from 7.0 percent to nearly 10.0 percent in just nine months. This culminated in October 1987’s Black Monday crash, where the S&P 500 lost more than 20 percent of its value in a single trading day.

In rushed newly appointed Fed Chair Alan Greenspan, who began to erode the old way of things in response to the crash. Greenspan, a gold bug in an earlier age, ran the Fed’s printing presses red-hot and flooded the system with money. Since then, whenever the U.S. economy has gotten into trouble, the Fed has flooded the system with ever more money, buying up U.S. government debt. In response, U.S. rates have marched lower and lower.

Inflation doesn’t exist. Greenspan’s mistake in 1987 effectively made running budget deficits much less painful for politicians. But the Fed’s low rates usually would stoke inflation, which was painful for working Americans and would prompt the Fed to eventually end the easy money. That changed with the onset of globalization.

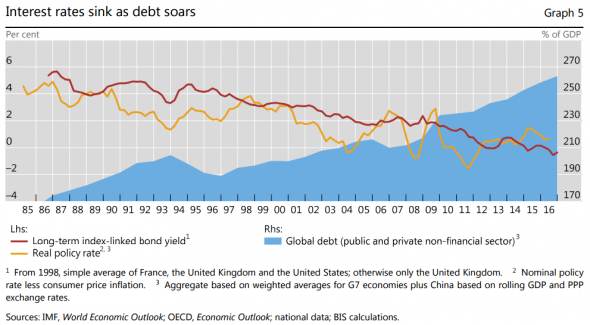

In the 1990s and 2000s, the Fed kept rates low but inflation never spiked. Claudio Borio, head of the Monetary and Economic Department at the Bank for International Settlements, reasons that globalization and cheap goods coming out of Asia suppressed inflation in the developed world. This fooled central bankers into keeping rates too low for too long, and the result was cheap credit and a reach for yield—investors taking on excessive risk to maintain returns as returns for safer assets are pushed lower—which led to booms and busts in property and stocks.

In Borio’s words: “As long as inflation does not rise much during booms, partly held back by the tailwinds of globalization and by central bank credibility, a monetary policy focused on near-term price stability has little incentive to tighten to restrain the build-up of financial imbalances. But then it has every reason to ease aggressively and persistently if the economy weakens…”

The borrowing binges that created the booms stole resources from the manufacturing sector and shifted them to the construction sector, which suppressed long-term growth after the boom had turned to bust. Worse still, the end of the boom has always resulted in central banks doubling down on the failed monetary status quo and lowering rates even further, which only reinforces the original error.

According to Borio, doubling down on lower rates “imparts a downward bias to interest rates and an upward bias to (private and public) debt that at some point makes it hard to raise interest rates without damaging the economy. The accumulation of debt and the distortions in production and investment patterns induced by persistently low interest rates hinder the return of those rates to more normal levels.”

So instead of widespread inflation, central bankers have been creating asset bubble after asset bubble with cheap credit. To explain the reach for yield, imagine a pension fund manager who needs a 10 percent return every year to pay teachers, firefighters, and police officers. Several decades ago, much of the fund could be invested in the relatively safe 10-year Treasury bond. As Treasury yields have fallen, more of the fund must now be allocated to risky investments to meet the required 10 percent nominal return.

For another example of the booms and busts that cheap credit can cause, think of automobiles. When it is easy to borrow and buy a car, the price of cars takes off due to outsized demand. When the cost of capital exceeds its return for investors in auto loans due to some combination of too much supply or credit-fueled demand running out, prices of the good or financial contract fall quick and hard. This happens economy-wide in what has come to be known as a Minsky Moment.

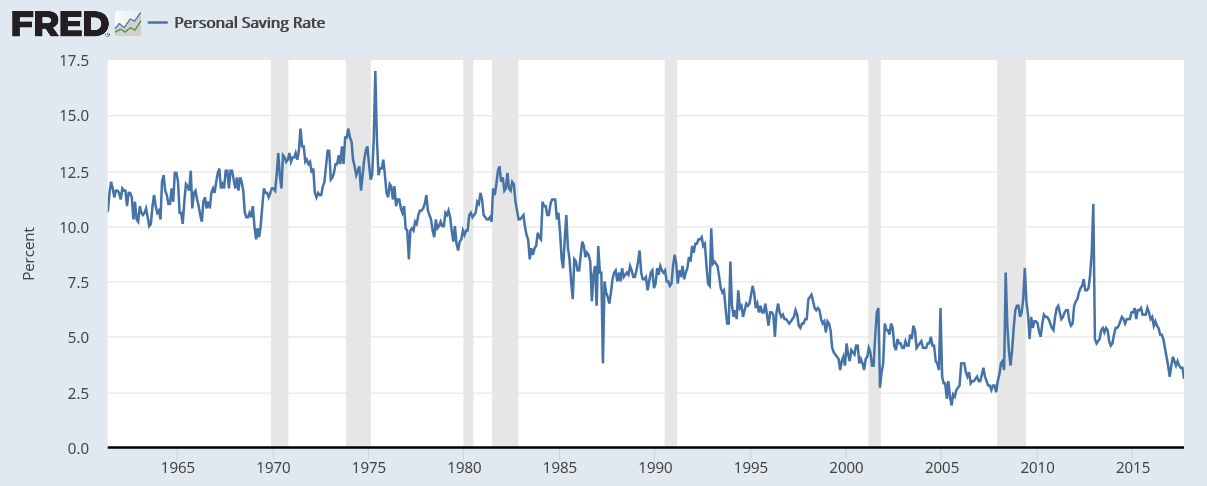

Debt-fueled demand. The Fed’s monetary policy has changed Americans’ saving and spending habits too. During the last 30 years, U.S. debt levels have skyrocketed and household savings have plummeted. This makes sense. Cheaper borrowing means more borrowing, and lower returns for saving means less saving.

The household leverage ratio went from a steady 80 percent pre-1970 to 130 percent by 1990 to an unstable 220 percent in pre-crisis 2008. Public debt in 1980 was only 31 percent of GDP compared to more than 100 percent today. Total government, business, household, and financial debt was about 1.8X national income (GDP) in 1980, compared with 3.5X today. That deserves some emphasis. For much of this county’s history, total debt hovered around a healthy 1.5X national income. In just 40 years, that historical ratio increased by two turns, to 3.5X.

As American wages stagnated, more Americans looked to increase or even just maintain their standard of living by borrowing, and households levered up using their homes as collateral. This corresponded with a drop in savings. The savings rate went from almost 10 percent in the early ‘90s to less than 5 percent by the end of that decade.

The foundation of capitalism is savings. Savings are how we get investment. Investment by businesses increases the capital stock, or productive capacity, of an economy (capital stock includes such things as factories and equipment). The increased productivity of workers, the ability to do more in a given period of time, that results from increased business investment increases real wages. Household savings are also, quite obviously, a reservoir of future consumer demand.

Why Real Wages Have Been Flat for So Many Americans

Bad policy choices at the Federal Reserve, targeting inflation despite globalization and continually flooding the financial system with money at the onset of every crisis, have been toxic for the blue-collar American worker, for two reasons.

It’s a nominal-dollar world. The Fed’s belief that the economy is stable if inflation is running at a steady clip, regardless what is happening with credit, has prompted it to adopt a ludicrous and arbitrary 2 percent inflation target. This might have worked out well pre-globalization, but the combination of exiting Bretton Woods and liberalizing trade made this policy disastrous for low-skilled, goods-producing U.S. jobs.

Because of the Fed’s inflation target, since 1987 alone, the price level in America as measured by the Bureau of Labor Statistics has just about doubled (inflation has averaged just under 3 percent since 1987). This means if American workers were paid two times today what they were paid in 1987, in real terms—assuming the BLS is measuring inflation correctly—they would be making the same wage now that they were making back then.

But as the nominal cost of hiring Americans has increased, foreign nominal wages, priced in dollars, have not risen quite as fast. This has made lower-skilled American labor increasingly uncompetitive in industries where the labor can be easily offshored to China or India. Even Germany’s nominal wages haven’t increased as fast as America’s during the last 40 years.

Yet even if wages increased nominally, productivity growth increases due to increased business investment should have kept jobs in the United States. For example, Kenya’s wages are cheaper than China’s in dollar terms, but Kenya has far lower productivity than does China, so China is a more attractive place to produce things. To explain the lack of productivity growth, a further explanation is needed.

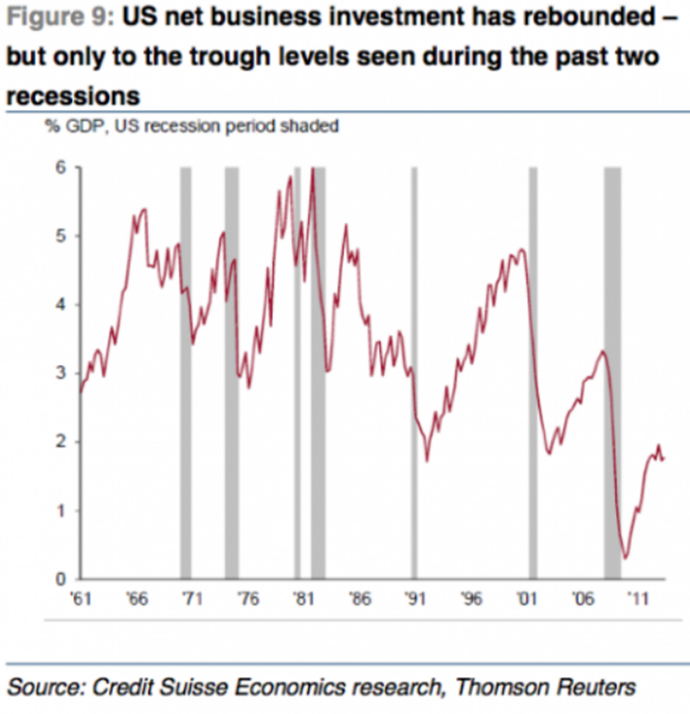

Low rates stifle long-term investment. At some time in the last 30 years, and especially since the early 2000s, low rates began to stifle business investment. Again, business investment is necessary to increase real wages and boost our standard of living. Don’t firms borrow and spend more when rates are low? The answer is mostly yes, but what firms spend their money on matters a great deal.

Although corporate debt as a percent of GDP has never been higher, many corporations are sitting on loads of cash, making businesses in America net savers. This is bad. Ideally, households would be the bigger savers and businesses would use those savings for productive investments. When corporations are investing and spending money, they have favored short-term investments (investments that will pay off in the next couple of years) and share buybacks over long-term investments.

Short-sighted politicians like Hillary Clinton have ripped capitalism during this recovery for short-termism. But the problem isn’t capitalism. Small- and medium-sized businesses (non-publicly traded companies) also haven’t invested like they used to. These businesses aren’t growing bigger like they used to either, while business startups are at a depressing 40-year low. Republicans like to blame Dodd-Frank. Dodd-Frank is a bad law, but these trends predate Dodd-Frank, and much of the evidence points to a lack of demand for loans, not a lack of supply. In other words, just like their publicly traded brethren, small- and medium-sized American businesses are reluctant to make long-term investments.

Why are businesses reluctant to tie up money for more than a couple years? First, high consumer debt and low consumer savings means firms are skeptical about long-term demand. Think of it this way. When you run up your credit card and don’t have a lot of cash stored away, you need to hunker down for a while before you can spend again.

A Bank of England survey found that British firms were hoping to achieve at least a 12 percent return on investment for potential projects, the average return target for previous business cycles, even though the cost of capital during this cycle was much lower than before. In other words, business perceives an increased risk when making long-term investments even as the cost of funding that investment is now lower than ever.

Second and highly related to the first, many firms have been burned by booms and busts in the past, which also makes them unsure of future demand. Consider the construction industry. The Economist has reported that productivity in the construction industry is at an historic low because firms are gorging themselves on variable (short term) costs, while trying to minimize fixed costs. The reasoning is simple. When a downturn hits, variable costs can be cut, while fixed costs, by definition, cannot be quickly cut in response to a fall in demand.

This seems to be occurring economy-wide, and disproportionately hurts blue-collar workers and working class wages. Firms that depend on high-cost human capital, like law firms or accounting firms, often have higher variable costs. These jobs command higher wages because workers can’t easily be replaced by someone new, and employees thus have more bargaining power.

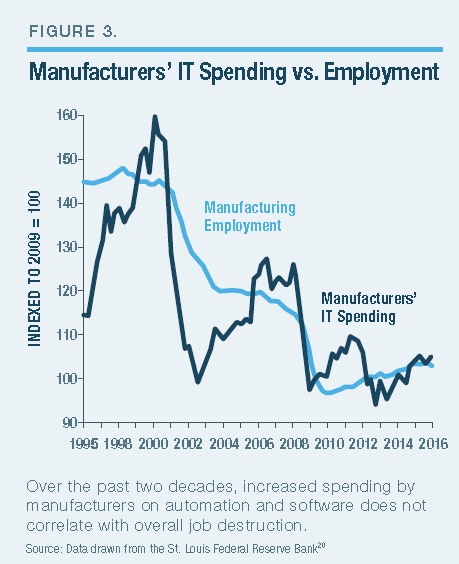

In industries that rely on less-skilled or lower-cost labor, increased productivity often comes from greater long-term business investment. If firms lose a taste for long-term investment, this disproportionately harms working-class Americans. For example, people like to blame automation for the secular decline of the manufacturing sector, but there is no evidence to support this (see right). If anything, more investment in automation is needed in blue-collar sectors to make workers more productive.

If productivity in blue-collar jobs is to be enhanced through greater human capital instead of investment in capital equipment, extensive on-the-job training is required. But on-the-job training is in decline too, another example of firms wishing to make as little long-term commitments as possible. According to The Economist, “[i]n its 2015 Economic Report of the President, America’s Council of Economic Advisers found that the share of the country’s workers receiving either paid-for or on-the-job training had fallen steadily between 1996 and 2008.”

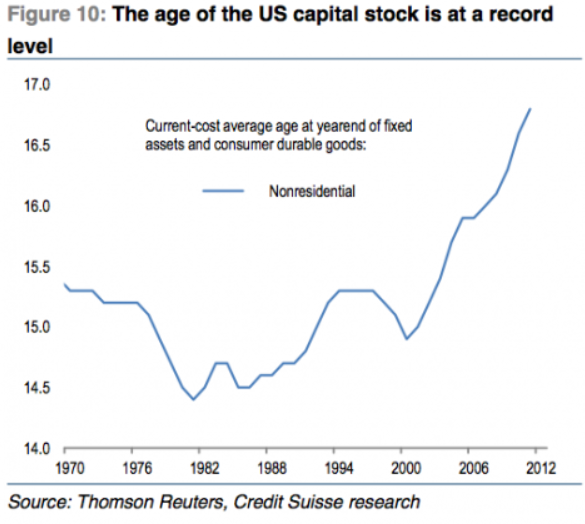

The end result of low business investment is not just lower U.S. wage growth now, but a deterioration of our capital stock—our economy’s productive capacity going forward—as existing capital spending doesn’t make up for depreciation (equipment wearing out over time).

Low rates misallocate resources. A final factor is that low rates allow unproductive firms to survive, which consumes labor, capital, and resources that would normally be consumed by more productive firms. These unproductive firms—defined here as firms that are unable to service debt obligations from existing operational cash flow for three consecutive years, but are kept alive by borrowing—make up a stunning 8 percent of companies in the Russell 3000 stock index (the largest 3000 publicly traded firms in America), according to Cornerstone Macro, a research provider.

Corporate bankruptcies are way down, only because these firms don’t die, which is why these unproductive companies are popularly known as zombie firms. Zombie firms alone explain a good deal of the below-trend GDP and productivity growth. But how is the lack of competition and high profits for many successful American companies squared with the rise of the zombies?

The answer is quite simple. Because zombies are consuming too many workers and resources in some industries and sectors, potential Davids that would take on the highly profitable Goliaths in other areas of our economy don’t have the resources to do so. This lack of competition among the big and successful corporations is harmful too, pushing up prices for consumers and hurting U.S. growth, wages, and labor force participation.

All this helps explain why our economy seems to have ossified. Without making big capital investments (big risks), firms aren’t moving up the ladder to compete. Firms already on the top can raise prices because even though profits are high, the marginal return on capital for potential competitors, invested too far into the future, is too low to compensate for the risk caused by the monetary status quo.

What to Do About Our Economic Malaise

The culmination of these repeated policy mistakes has led us to where we are today. In the wake of the last financial crisis, Americans are still hurting and the recovery is still the weakest on record since World War II. The middle class is shrinking, and more than the majority of working Americans live paycheck to paycheck. Despite the slow growth, the Fed has a $4.5 trillion balance sheet, and short-term rates the Fed sets are in the basement of history.

This is why Trump’s nomination of Powell is so unfortunate. Powell has said he is “strongly committed” to the Fed’s 2 percent inflation targeting regime. Because of this, he will likely keep rates too low for too long, as did his predecessors.

When another recession hits, a status quo Fed will double down yet again on more asset purchases of government debt—known as quantitative easing—and probably take short-term (interbank) interest rates into negative territory, as has been done in Europe and Japan. Asset prices will rise again, the vast majority of which the rich own, while real wages will stagnate or slide further. The monetary doom loop will then continue, at the expense of Main Street USA.

Is all hope lost? The good news is that Senate conservatives still have a shot at pressing Powell on the following important issues during his confirmation hearing.

President Trump blames trade and China for our malaise. Yes, China cheats at trade, and in so doing harms investment in U.S. industries subject to Chinese competition. By all means we should crack down on the cheating. But blaming China is like shooting the messenger. China and globalization have defenestrated the central bankers’ Phillips curve-based economic models, and central bankers have yet to wake up to this reality. Is Powell pragmatic enough to ditch the Fed’s failed models from a world before globalization took hold?

In other words, America needs a total change of monetary policy framework. This means the Federal Reserve should not be looking at stable inflation as the sole indicator of macroeconomic stability. It is entirely possible to have a credit crisis while maintaining “price stability.” Borio has proposed that central bankers abandon simplistic inflation targeting and instead try to keep credit growth in line with incomes. This seems like a good idea.

The Fed should also adopt a rules-based approach which, aside from examining credit, takes account of changes in productivity and nominal GDP. The current congressional mandate to the Fed—Humphrey Hawkins—that focuses on price stability and full employment should be done away with, and the Fed should abandon its 2 percent inflation target. Fortunately, Congress can get this done whether Powell is Fed chair or not. This would lead to a more stable credit cycle, more competitive nominal wages, and productivity gains from greater and more productive business investment. All these things would boost Americans’ real wages and standard of living.

Finally, the Fed needs to acknowledge the damage that its money-printing and bond-buying has caused working Americans, who depend on their savings to rise into the upper-middle-class. For a decade, savings rates in real terms have been negative. The Fed’s quantitative easing (printing money to buy government bonds) causes money and wealth to move to certain areas of the economy—financial assets—and not others.

If certain assets get “inflation” while people’s wages do not, this redistributes wealth from middle-class savers to the wealthy owners of financial assets. Senators should make sure Powell doesn’t double down on quantitative easing the next time a recession hits. If Powell seems wholly ignorant to the shortcomings of our prevailing monetary policy status quo, lawmakers shouldn’t be afraid to oppose his nomination.

The other good news is that you, readers, vote. Conservative voters need to watch how their representatives question Powell and vote on his nomination. Many Republicans think conservatives have no problem with a big-government Fed that enables big spending in Washington. Voters should ask Republican candidates during primaries what they think about Fed policy, and how they would vote on these issues.

Voters should look up how their representatives have voted on Rand Paul’s audit the Fed bill, too. No, the bill isn’t trying to take away central bank independence, and yes, the Fed deserves much greater oversight. Changing the prevailing monetary policy status quo won’t be easy, but it will be well worth the effort.