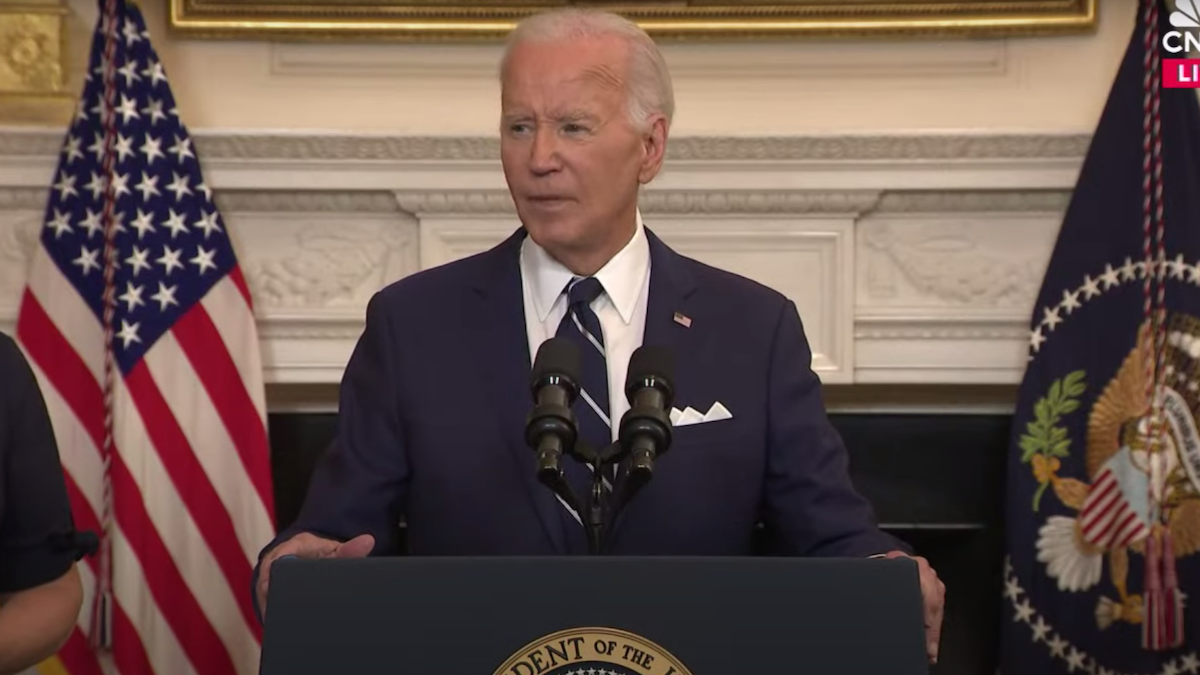

News that North Korea has successfully miniaturized a nuclear weapon that can fit onto an intercontinental ballistic missile, as the Washington Post reported Tuesday, has prompted much speculation about what we should do about it and who’s to blame.

One idea floating around is that we need an Iran-style nuclear deal with North Korea—and that if we’d had one, we wouldn’t be debating the merits of nuclear versus conventional war on the Korean peninsula, President Trump wouldn’t be blustering about “fire and fury,” and Pyongyang wouldn’t be publically mulling a ballistic missile strike on Guam.

Middle East scholar Andrew Exum tweeted Tuesday, “It sure ain’t perfect, but you know who North Korea is making look really good right now? The Iran deal.” Last month over at Foreign Policy, Jeffrey Lewis sarcastically noted that, “If you like North Korea’s nuclear-armed ICBM, you are going to love America walking away from the nuclear deal with Iran.”

His point of course is that scuttling the 2015 Iran deal, as Trump has repeatedly promised to do, will lead to another North Korea. By that same logic, striking an Iran-style deal with Pyongyang is the best we can hope for at this point. Robert Litwak, director of international security studies at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars (and the author of a book with the now-seemingly obsolete title, “Preventing North Korea’s Nuclear Breakout”) made precisely this argument back in May: “The template for preventing a North Korean nuclear breakout that could directly threaten the United States is the Iran nuclear agreement.”

The problem is, we had an Iran-style nuclear deal with North Korea, and now North Korea has nuclear weapons.

A Brief History Of North Korea’s Nukes

North Korea signed the nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) in 1985, but it had been working on nuclear weapons for years. After ’85, it evaded inspections from the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) until, under mounting pressure, it declared in 1993 that it was withdrawing from the treaty. North Korea then began removing fuel rods from its nuclear reactor at Yongbyon, which would yield enough plutonium to make a bomb.

That prompted President Bill Clinton to negotiate what was known as the Agreed Framework, which North Korea and the United States signed in 1994. Basically, it froze Pyongyang’s nuclear program and replaced its plutonium reactor with two light-water reactors. The United States agreed to supply the North with a half-million tons of heavy fuel oil every year for heating and electricity generation.

The Agreed Framework had some striking similarities to the Iran deal: it wasn’t a treaty and therefore didn’t require ratification by the Senate, it was focused almost exclusively on curbing North Korea’s pursuit of a nuclear bomb, and it was to be overseen by an international body.

In theory, the Agreed Framework rendered the Yongbyon reactor harmless for eight years—until the deal collapsed because Pyongyang was caught cheating. In practice, North Korea began developing a secret, underground uranium enrichment program at Kumchangri as early as 1996.

In 2002, when the George W. Bush administration called out North Korea for violating the Agreed Framework, North Korea angrily acknowledged it, then announced it was withdrawing (again) from the NPT. That prompted the six-party talks, in which the United States, China, Russia, Japan, and North and South Korea tried to work out a new agreement. In October 2006, while the six-party talks were still painstakingly underway, North Korea detonated a nuclear bomb. The talks dragged on until April 2009, when North Korea announced it was withdrawing from negotiations, resuming its nuclear program, and kicking nuclear inspectors out of the country.

Making The Same Mistake In Iran We Made In North Korea

So what went wrong? How did North Korea wind up with a nuclear arsenal despite the myriad incentives and decades-long international efforts to prevent them from getting one?

I asked David Albright, the president of the Institute for Science and International Security, and a renowned expert on nuclear proliferation, and he told me the fundamental mistake in the Agreed Framework and the six-party talks was that the United States didn’t insist on robust IAEA inspections of military sites to get to the bottom of North Korea’s nuclear weapons program and ensure they weren’t cheating.

“Once North Korea knew they could get away with it, they began to cheat,” says Albright. “They had no intention of letting the IAEA inspect military sites.”

According to Albright, the big mistake we made in North Korea is the exact same one we’re making in Iran: not letting the IAEA do its job. North Korea expelled the agency and promised it would get to come back, but that never happened. To get North Korea to agree to a deal, the United States never insisted on a robust inspections regime that included allowing the IAEA access to military sites.

That’s exactly what we did in negotiating the Iran deal; IAEA inspections of military sites were excluded to preserve the agreement. Much like the Clinton administration did with Pyongyang in 1995, the Obama administration created a dynamic whereby U.S. negotiators were scared to push for the inspection of military sites out of fear that Tehran would say “no” and the deal would collapse.

“We’re making the same mistake because we’re scared of failure and war,” says Albright, recalling that at the time of the Agreed Framework, U.S. negotiators were casting the IAEA as the villains, saying the agency was going to cause a war. “The United States should have insisted that the IAEA be allowed to do its job.”

It’s hard to overstate the importance of inspections. The six-party talks ultimately fell apart because the Bush administration insisted on robust inspections, and that’s when North Korea walked away.

There’s one other important way the Iran deal mirrors our failed negotiations with North Korea: it’s predicated on a strict timeline that assumes too much. The Iran deal guaranteed a sunset on the arms embargo after five years, inter-continental ballistic missiles after eight years, and certain nuclear conditions after ten years. In a similar way, the Agreed Framework contained a built-in timeline. North Korea would come clean, allow for robust inspections, then get the nuclear reactors that had been promised.

In both cases, the timelines were based on certain assumptions. The belief in 1994 was that North Korea would never actually agree to all the provisions in the deal, but the assumption was that the Kim regime wouldn’t even exist by 1998—North Korea would by then be finished as a hostile communist power. The Obama administration’s assumption was that by the time Iran is capable of going nuclear, it will be reformed by “moderates” like President Hassan Rouhani and be a responsible member of the international community.

None of this is to say we shouldn’t try to negotiate with hostile regimes like Iran and North Korea before resorting to military options, or that Trump should completely walk away from the Iran deal in its entirety. But anyone arguing that North Korea’s nuclear capabilities bolster the case for the Iran deal doesn’t realize the similarities between U.S. efforts in both countries, or the reason our deal with North Korea ultimately fell apart.

“It’s not a model to follow,” says Albright. “The North Korea example of kicking can down the road is recipe for failure.”