Bill Nye has some detestable ideas about humanity. This shouldn’t surprise anyone. Many environmental doomsdayers share his totalitarian impulses (Nye has toyed with the idea of criminalizing speech he dislikes) and soft spot for eugenics.

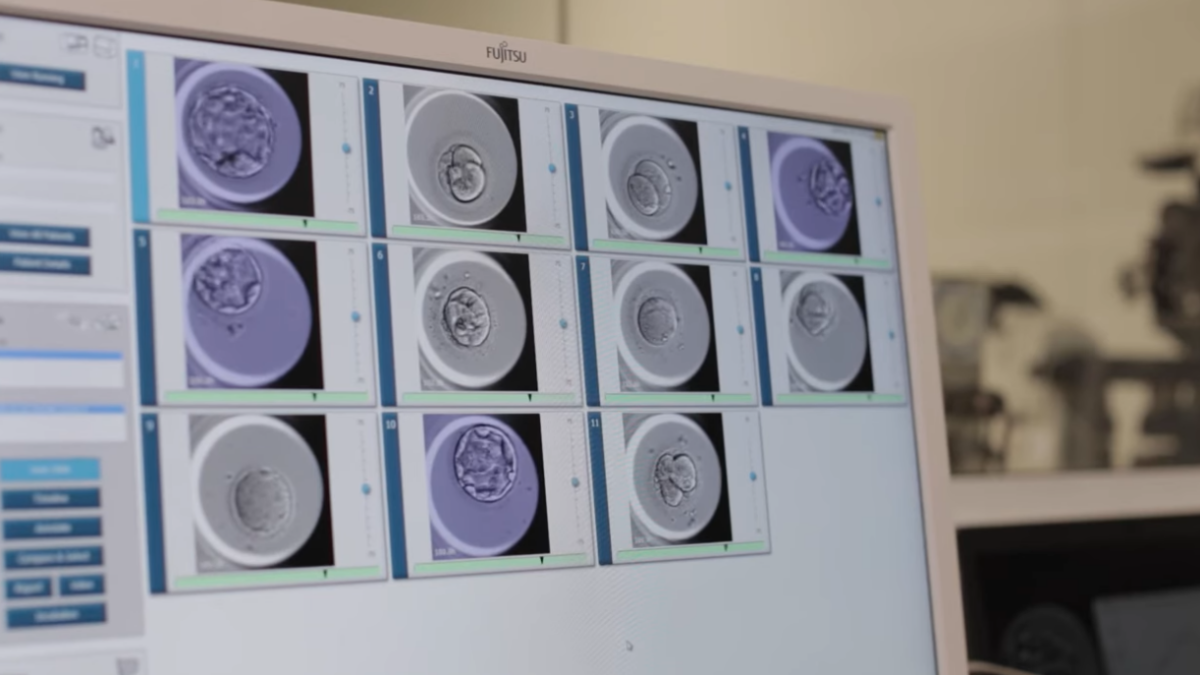

In his Netflix series, “Bill Nye Saves the World,” the former children’s television host supplies viewers with various trendy notions to adorn his ideological positions with the sheen of science. In the final episode, Nye and his guests contemplate a thorny “scientific” question: How the state can stop people from having “extra children.”

Nye: So, should we have policies that penalize people for having extra kids in the developed world?

Travis Rieder: I do think that we should at least consider it.

Nye: Well, ‘at least consider it’ is like ‘Do it.’

Rieder: One of the things that we could do that’s kind of least policy-ish is we could encourage our culture and our norms to change, right?

All of this was pretty familiar to me, and not only because the panel sounded like a ChiCom planning meeting. The Nye segment, it turns out, was just a repetition of a 2016 NPR article on overpopulation featuring Rieder that I’d once written about.

“Should we have policies that penalize people for having extra kids in the developed world?” asked Reider and others who were pondering the “ethics of procreation.” The article is titled “Should We Be Having Kids in the Age of Climate Change?” In it, Rieder, a philosopher with the Berman Institute of Bioethics at Johns Hopkins University, scaremongers a class of college students about The End of Days and the immorality of having children. “The room is quiet,” NPR explains, “No one fidgets. Later, a few students say they had no idea the situation was so bad.” It’s not.

“Here’s a provocative thought,” Rieder says. “Maybe we should protect our kids by not having them.” This is provocative in the way a stoner wondering why airplanes don’t run on hemp is provocative. That’s because the entire case for capping the number of children rests on assumptions entirely devoid of scientific or historical basis.

In 1798, Thomas Malthus wrote that “the power of population is indefinitely greater than the power in the earth to produce subsistence for man.” At that point, there were maybe a billion humans on the Earth, so we might forgive him for worrying. In 1800, the life expectancy of the average British citizen — then the leading light of the world — was 39 years of age. Most humans lived in pitiless poverty that is increasingly rare in most parts of the contemporary world.

Now, had Nye been around in the early nineteenth century, he’d almost surely be smearing anyone skeptical of the miasmatic theory of disease. The problem is he lacks imagination, unable to understand that science is here to help humanity adapt and overcome, not to constrict it. Anyway, six-plus billion people later, extreme poverty has fallen below 10 percent for the first time ever. Most of those gains have been made in the midst of the world’s largest population explosion.

As I’ve noted elsewhere, according to the World Bank, because of the spread of trade, technological advances, and plentiful fossil fuel, not only are fewer people living in extreme poverty, but fewer are hungry than ever; fewer die in conflicts over resources, and deaths due to extreme weather have been dramatically declining for a century (evidence The Science Guy regularly ignores). Over the past 40 years, our water and air has become cleaner, despite a huge spike in population growth. Some of the Earth’s richest people live in some of its densest cities.

It’s worth remembering that not only was early progressivism steeped in eugenics, but early ’70s abortion politics was played out in the shadow of Paul Ehrlich’s “population bomb” theory. Vice President Al Gore has already broached the idea of “fertility management.” “Frankly,” Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg mentioned a few years ago, “I had thought that at the time Roe was decided, there was concern about population growth and particularly growth in populations that we don’t want to have too many of.”

You thought right. Today, abortion is used as a means of exterminating a class of human deemed unworthy of life.

We live in a world where Ehrlich protégé John Holdren, who, like his mentor, made a career of offering memorably erroneous predictions (not out of the ordinary for alarmists), can become a science czar in the Obama administration. Holdren co-authored a book in late 1970s, called “Ecoscience: Population, Resources, Environment,” that waded into theoretical talk about mass sterilizations and forced abortions in an effort to save hundreds of millions from sure death. Nye is a fellow denier of one of the most irrefutable facts about mankind: human ingenuity overcomes demand.

Now, just because something hasn’t happened yet doesn’t mean it can’t happen in the future. But the evidence against Malthusianism is stronger now than it has ever been. Of course, not everything about human existence can be quantified. This is the point. Talking about humans as if they were a malady that needs to be cured is, at its core, immoral. And listening to a man who has three residences lecture potential parents about their responsibilities to Mother Earth is particularly galling.

Although many thousands of incredibly smart and talented people engage in real scientific inquiry and discovery, “science” is often used as a cudgel to browbeat people into accepting progressive policies. Just look at the coverage of the March for Science last week. The biggest clue that it was nothing more than another political event is that Nye was a keynote speaker.

“We are marching today to remind people everywhere, our lawmakers especially,” he told the crowd, “of the significance of science for our health and prosperity.” Fortunately, our health and prosperity has blossomed, despite the work of Nye and his ideological ancestors.