Politics is the last thing that enters the mind of visitors to art museums. As modern pilgrimage sites, museums are venerated as sanctuaries of pure, unspotted Culture. That piety makes art exhibitions a credible vehicle to displace history with ideology. Add a Kuwaiti princess to a prestigious museum’s board of directors, and the subordination of culture to politics is guaranteed.

“Jerusalem 1000 to 1400: Every People Under Heaven” at the Metropolitan Museum of Art is a sophisticated exercise in historical revision and cultural proselytizing. Between cherry-picked anecdotes, crucial omissions, and the lyrical come-ons of Conde Nast Traveler, the ravishing catalogue conjures an Islam cleansed of imperialism, brutality, absolutism, and institutionalized inequality of non-Muslims. Here instead is an Islam shimmering with benignity and civilized taste, a light to the nations.

The paradisiac myth of convivencia—peaceful coexistence between “three Abrahamic faiths”—arrives splendidly packaged, relocated from Andalusia under the caliphate to Jerusalem. In the Metropolitan’s telling, medieval Jerusalem was al-Andalus in Palestine. A flourishing multicultural Arcadia, its magnificence and diversity testified to the enlightened tolerance of Islamic domination.

We’ll Get Along If We Can Destroy Your Sacred Sites

Sleight of mind begins at the starting gate. An outsized projection of the Dome of the Rock dominates the wall that meets your eye on entering. It commands high center, overshadowing several smaller images of other sites flanking it. Built in the late seventh century in the appropriated style of a Byzantine martyrium, the Dome is an architectural symbol of Islamic ascendency. Visual arrangement conveys a subtle message: Jerusalem belongs to Islam.

The initial wall text adopts the upbeat tones of a tour guide: “Beginning about the year 1000, Jerusalem captivated the world’s attention as never before.” True. But our guide omits the reason: In 1009-10, Fatimid caliph al-Hakim bi-Amr Allah ordered the destruction of all synagogues and churches throughout Palestine, Egypt, and Syria, including the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem.

His demolition left the city in tatters. It was one of the final triggers that, after centuries of Islamic assault on what was then Christian territory, led to the Crusades decades later. Like Spain’s reconquista, the Crusades began in response to Muslim invasion and subjugation. In 1095, the Byzantine Emperor Alexius Comnenus begged Pope Urban II to send forces to repel the Seljuk Turks, non-Arab converts to Islam who were then in control of Jerusalem and advancing on Constantinople.

As the crusaders approached, the Fatimid governor of Jerusalem expelled the city’s Christians. (Expulsion of an adversarial population was common in medieval warfare and practiced by all antagonists.) But history is putty in an exhibition intent on flattering Islamic culture.

The tutorial moves quickly to the predictable wisdom: “In 1099, European Christians achieved their improbable dream of conquering and claiming faraway Jerusalem as theirs.” Counter to historical reality, the wording suggests unprovoked, expansionist “Western warriors” (the catalogue’s phrase) attacked and colonized blameless Muslims. Instruction continues: “In 1187, the military leader Saladin retook the city and dedicated its Islamic sanctuaries (“rededicated,” in the catalogue). In the late 1200s through the 1300s, Mamluk sultans, blessed with stable regimes, promoted the city as a spiritual and scholarly center.”

Christians conquer, but Muslims reclaim and retake. The catalogue gives us crusaders who “mercilessly slaughtered,” in contrast to Muslims who “take back Jerusalem” to create a spiritual and scholarly center of rare pluralism: “Venice, Rome, Paris—none of these cities tolerated the same degree of religious diversity.” In just that way, the catalogue repeats and affirms conventional misconceptions about one of the most misunderstood periods in Western history.

Wishful Academic Fantasy Is Not Historical Evidence

Jerusalem, a small city, was askance of major trade routes and did not manufacture much beyond souvenirs for pilgrims. As historian Diarmaid MacCulloch once phrased it: “Its industry has been sacredness ever since its first gnomic appearance in the pages of biblical history.”

Medieval Jerusalem owed its prosperity to pilgrims, particularly Christian penitents who traveled to the Holy Land at risk of capture, rape, or death. The museum narrative, however, presents medieval Jerusalem as a Levantine theme park, paved with dinars and hopping with discerning tourists, upmarket pilgrims, and broadminded intellectual elites.

Curatorial spotlight on “the various aesthetic strands that made medieval Jerusalem a magnet for so many” substitutes spectacle for historical understanding. It permits the beauty of artifacts to override such bothersome realities as Islamic law’s divinely ordained subordination and degradation of Christians and Jews. Instead, it dresses the city’s bloodied history in terms adapted to modern sightseers on holiday:

Suppose we set aside political history as a means to define cultural history so that we could better explore the variety, richness, continuities, and interconnectivity of the city, its people, and its art?

All pluralists now, polite audiences believe in the Tinkerbell of diversity. The museum obliges. It projects back in time current notions of inclusiveness and interfaith comity. Buying and selling prompted goodwill. Ethnic tumult and religious hatreds melted in commercial exchange: “Trade and travel between Europe and the Holy Land provided common cause, even in times of war, and afforded peoples from different worlds opportunities to meet through the shared language of commerce.”

The “common pleasures of eating and drinking” were another bridge to fellowship. Here was Diners Club by the Dead Sea: “No visitor to Jerusalem failed to mention the food… The abundance and assortment of foods were remarkable. Al-Muqaddasi held the conviction God himself had provided the wide array of delicacies in his native land…”

Given Islamic prohibition of alcohol, what were they drinking? And with whom? Religiously mandated exclusionary laws were strictly observed by Muslims toward Christians and Jews, and by Christians and Jews toward Muslims and each other as well. Muslim fear of defilement by contact with clothing, utensils, food, and water touched by Christians did not make for camaraderie.

The narrative cannot resist a tell-tale dig at the inferiority of Christian cuisine. For the city’s surviving Christian remnant, food sale was restricted to “a street whose name carried its own implicit warning: Malquisinat Street” [Street of Bad Cooking]. Qur’anic obligation to humble the infidel extended even to the table—though the Islamophilic narrative does not state it that way.

Assimilation Does Not Mean What You Think It Means

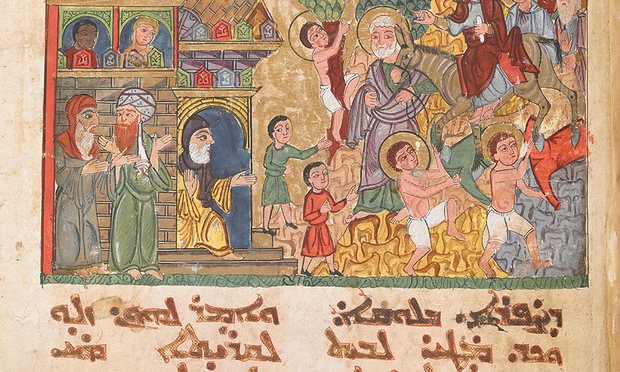

What it does do is distort the past with insidious half-truths: “By the ninth century Arab Christians had acculturated into Islamic society.” So, they spoke and wrote Arabic. But the wording lulls readers into making a false equation between the situation of Christians under Islam and our own assumptions about the assimilation of immigrants. Acculturated Christians were those who endured degraded status, the climate of fear that accompanied it, and the tyranny of the jizya in order to stay alive.

No reference to dhimmitude appears in the catalogue’s 333 pages. Typical of mainstream scholarship devoted to the myth of Islamic benevolence, the text ignores the conditions imposed on the masses of Christians and Jews. Sharia-mandated abasement disappears. Rather, the narrative features isolated vignettes of intellectuals, poets, scholars—“the flourishing academic scene”—and fantasies of “fluid religious identity.”

Religious identity was especially relaxed in medicine, we learn. These “doctors without borders” could “help bridge the divides between cultures.” Missing is any mention of the circumstances of these physicians, many of them despised dhimmi who practiced a necessary craft under conditions of servitude.

One name on the dizzying roster of exhibition acknowledgments demands attention: Sheikha Hussah Sabah al-Salem al-Sabah. A Kuwaiti princess, her excellency is director of Kuwait’s Dar-al-Athar al-Islamiyyah (DIA), created to house—and lend—the al-Sabah Collection of Islamic art, possibly the largest in the world. Among other influential roles, she is a former macher with the Islamic Research Centre for History, Arts and Culture in Istanbul, Turkey.

In joining the Metropolitan’s board, Sheikha Hussah brings the museum more than petrodollars. She comes with a mission: to alter Western perception of Islam. Art is the chosen vehicle for conversion. She is committed to the ability of art “to open people’s minds as well as their eyes to the splendor of Islam.” Her activism conforms to the recommendations of the Organization of Islamic Conferences (OIA) to portray a radiant image of Islam “by all available means and channels.”

Visitors exit the exhibition through a gift shop. For sale next to the catalogue are copies of Karen Armstrong’s “Jerusalem: One City, Three Faiths” (1996). An apologist for Islam and defender of Mohammed the “peacemaker,” the ex-nun is a much-hyped popularizer of the sanitized vision of Islam the exhibition promotes. Its placement here carries a message.

The exhibition was fortuitously timed. Installed at the end of September, it opened shortly before UNESCO’s October 13 resolution to override thousands of years of Jewish ties to Jerusalem and negate any exceptional Jewish connection to the Temple Mount and the Western Wall. By the time day trippers work their way through the galleries, they will have absorbed impressions that lend credence to the UNESCO directive.

Call it jihad-by-other-means.