A few years ago, thrifted jean jackets and plaid shirts were a hallmark of Portland hipsters. Now, similarly vintage styles are runway fashion.

While it’s tempting to think of vintage trends—and fashion in general—as the result of nothing more than clever marketing and artifice, the fashion industry is still a part of the free-market system. As such, it thrives because its finger rests firmly on the pulse of society.

Millennials now have major purchasing power, and we’re projected to increase our market influence to $8.5 trillion by 2025. Pivoting to reach the next generation of consumers, fashion is adapting to reflect us. What we wear indicates our state of mind. Judging from the most recent trends, we’re a pretty tortured bunch.

Lingering 1960s Envy

Since the first Obama campaign, identity politics have surged into the center of American activism. Feminism is more politically correct than ever, and between Ferguson rallies, Black Lives Matter, and university protests across the country, millennials are in the midst of a sixties throwback moment. Is it an accident, then, that ’60s fashion has also resurged in recent years?

While many credit “Mad Men” with the popularity of mid-century modern, it’s impossible to disconnect the Twiggy-esque pixie cuts, sharp bangs, and minimalistic shift dresses from the ’60s Love Generation. As social media activists take down public figures for any whiff of “cultural appropriation,” “anti-feminism,” or privilege, the urge is to be on the “right side of history.” Steeped in Selma envy, millennials are eager to find and fight an injustice as horrendous as Jim Crow.

Individuals may balk at the idea that they’re obsessed with emulating the past, but it’s hard to argue when their style says otherwise. Call it a search for meaning. Assured during childhood of our special snowflake status and our infinite ability to “make a difference,” millennials want to test the truth of those statements. We want to make a difference.

Just somebody, please, tell us how. We’re having a hard time taking a stand on clear ethical issues, while simultaneously rejecting traditional ethical frameworks.

The Vintage ‘90s

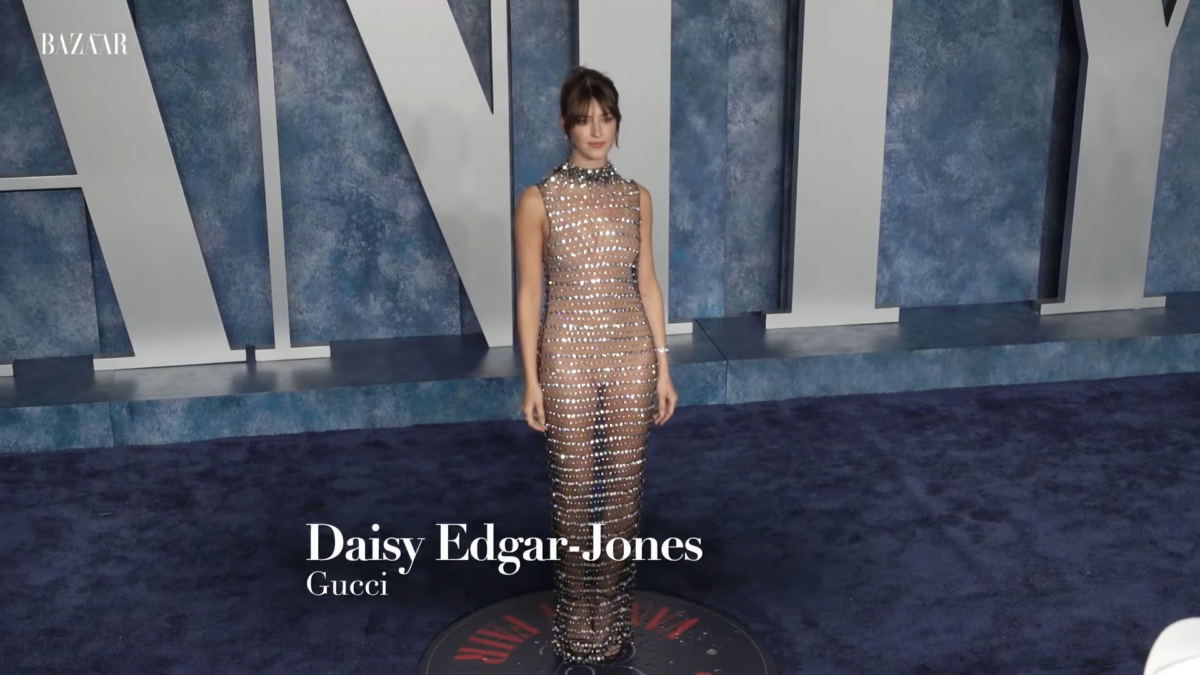

Oddly enough, 2016 is shaping up to be another throwback year. This go-round, it’s a weird mashup of the ‘70s and ‘90s. Retro parted bangs have already been sported by such notable figures as the Duchess of Cambridge and socialite Alexa Chung.

It’s also all about brown lipsticks and spaghetti straps that might’ve been pulled from Winona Ryder circa 1997. What’s most curious about this is not the decades themselves (although arguably the ‘90s throwback has to do with being a golden age for millennials), but what this recurring vintage means.

Of course, every age in fashion has drawn from the past. But the millennial obsession with vintage style is conspicuous. Raised on a diet of force-fed progressivism, we millennials inhale liberal ideas without knowing it, and find them at war with some innately conservative impulses.

We are a generation that saw our peers whisked off to daycare, which could be why we have higher rates of stay-at-home parenting than previous generations. This is a mighty traditional decision for a generation that, more than any other, labels itself “feminist.”

Many millennials are also drawn to socialism because they equate it—accurately or not—with the responsibility to help the poor. They’re unaware that the desire to care for the poor has deep roots in traditional conservatism (take Edmund Burke’s “Editorial on Irish Poverty”) because American conservatives have so often become “libertarian-lite” that the message is lost.

The appeal of socialism might simply be that it’s become (to millennials) the only government system that recognizes societies as interconnected, and proclaims clearly that the good life is not about self-interest. Yet in the midst of leftism, activism, and protests, we’ll still purchase anything that promises “heritage.”

After so many paisley prints and bellbottoms, it begins to look a little desperate. Perhaps all this rapid societal change has caused us to lose our way. It’s now taboo to feel proud of the past, yet we hunger to feel supported by it. Maybe it’s because the Republican Party has lost the meaning of true conservatism, trading tradition and localism for Trump-y populism or Bush-era big government.

With all the headlines about conservatism “dying out,” it’s fair to question if it was even really there. Or maybe millennials like vintage clothes because, finally, progressives are the ruling class. Younger generations are perennially rebellious against perceived power structures, and now that power talks and sounds like Berkeley, rebellion looks a lot like tradition.

Either way, if fashion has anything to teach us, it’s that millennials haven’t figured themselves out.