Forty-nine days before the 1932 presidential election, Gov. Franklin Delano Roosevelt stood before a capacity crowd in Sioux City, Iowa, and stated his aims for a new and more vibrant nation. Roosevelt preached a gospel of American exceptionalism against the pitfalls of Herbert Hoover using the words of Jesus in John 10:10 as the capstone of his speech: “I am come that they might have life, and that they might have it more abundantly.” Historian James MacGregor Burns described Roosevelt’s speeches as “sermons rather than statements of policy,” and on this day Roosevelt carefully wielded the “sword of the Spirit” against President Hoover in ways that politically wounded him.

The “abundant life” Jesus describes in John 10:10 became the source for a series of post-election speeches seeking to add divine authority to government programs designed to maximize the political power of the Democratic engine against what had come to be regarded as the unworkable (even immoral) claims of the Republican Party. Facing the headwinds of the Great Depression, Americans fastened to the promises of a president who bore the marks of spiritual power in a time when all other options seemed exhausted.

“The great objective which church and state demands is a more abundant life,” thundered Roosevelt on December 6, 1933. He would continue to pound the words of Jesus – albeit cloaked in terms of American nationalism – on the march toward a holistic revision of American constitutional standards. By 1934, he was heralded as “the Apostle of the New Deal” by W.D. O’Brien, a prominent Roman Catholic priest. The “gospel” of American exceptionalism was once again forging new paths through this, its latest “apostle.”

Presidents As Preachers

The fusion of theology and public policy has been evident from the earliest days of the American Republic. With language lifted from the Bible, the United States could best be understood in terms of an extended sermon with various applications from notable preachers disguised as presidents. American exceptionalism – with all its various implications both past and present – is historically and thematically explored by John D. Wilsey’s book, American Exceptionalism and Civil Religion: Reassessing the History of an Idea.

Probing the history of an idea as vague as American exceptionalism requires skill both to discover and interpret the words dotted across the history of American political writing. This is especially true of presidential rhetoric. The founding documents of the United States possess a bilingual capacity to fuse ideas radically opposed to one another in terms that can please all perspectives simultaneously.

For those who believe the American vision emanates from the political theory of John Locke, Baron de Montesquieu, and Jean-Jacques Rousseau, the Declaration of Independence and Constitution provide the grammatical and syntactical evidence for an Enlightenment-based vision free from the tyranny of religious despots. Conversely, for those who believe America is a fulfillment of biblical prophecies and typologies, there is ample evidence for a logical progression of such ideas throughout the American experiment.

What Wilsey accomplishes with a deft hand is identifying similar categories within the religious history of the United States where the language of the Bible has been used for political purposes. The idea of American exceptionalism is largely drawn from the Bible. The political concept itself cannot be accurately understood apart from understanding key biblical texts (2 Chronicles 7:14 as an example) and their influence at various times in American history.

Public Justice vs. National Idolatry

Just as the ideas of the Enlightenment categorically oppose the ideas contained in the special revelation of the Bible, the Christian gospel, if not properly understood, can categorically oppose the very concept of a nation possessing an exceptional identity. In other words, the problem Wilsey probes is the tension between public justice and national idolatry.

Wilsey presents the ideas of “closed exceptionalism” and “open exceptionalism” as ideas both harmful and beneficial to the church and the state. Closed exceptionalism views the nation in salvific terms, where political actions are one and the same with divine prerogatives as America itself becomes an “object of worship.” Transcendent authority is bestowed on the nation as it becomes God’s instrument for salvation to the world. Wilsey believes this understanding “paves the way toward heterodoxy at best, heresy and idolatry at worst.”

Open exceptionalism places the nation among all other nations of the world, and the church of Jesus Christ stands as the only agent of salvation. While national policies can point to a “moral and civic example” that leads to “compassion, justice, and general human flourishing,” the Old Testament idea of divine election of a nation (as in Israel) is no longer defining. It is replaced with the New Testament understanding of personal election by sovereign grace through the person and work of Jesus Christ.

Exceptionalism vs. Slavery

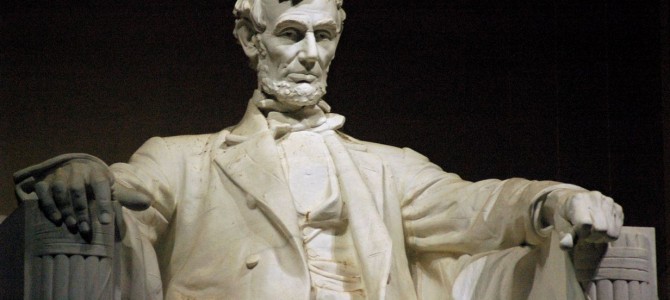

From the Founding era to the Civil War (roughly 1789-1861) closed exceptionalism took firm root in America, but Wilsey states that an accurate understanding of the Christian gospel should prohibit the nation from becoming an object of worship where absolute obedience to national policies is equated with obedience to God. During and immediately following the Civil War (1865 to the present) a more open exceptionalism surface,d as Lincoln’s political doctrine loosened direct application from the Bible to the American nation in terms where the United States was no longer politically interpreted as God’s chosen nation.

The Protestant Reformation is seminal in many of the ideas leading toward the American Revolution. Martin Luther’s interpretation of justification by faith in the book of Romans decoupled the traditional structures of the Roman Catholic Church from the formal power of the state. Ultimately, this would give rise to John Locke’s idea of religious toleration.

Jonathan Mayhew, an influential Boston pastor, practiced typological preaching borrowed from the Old Testament text of the Bible that equated the American people with the nation of Israel as they fled the slavery and bondage of Egypt. Ironically, the obvious impediment to the full liberty of the United States was slavery itself – the legal enslavement of humans against their will sanctioned under law by a supposed “holy” nation.

The march toward civil war could, in many ways, be described as a theological undertaking. Wilsey compares the writings of John L. O’Sullivan, influential editor of the United States Magazine and Democratic Review, who “equated democracy with Christianity,” to that of Abraham Lincoln, who grew to understand the equality clause in the Declaration of Independence as freedom of all, regardless of race.

A Different Path

O’Sullivan went so far as to suggest “that democratic principles were the animating force of Christianity, and that salvation itself was to be found not in the person and work of Christ, but in democracy.” O’Sullivan denied the principles of liberty to non-whites and created an “exclusionary system with an imperialistic agenda” that would inappropriately annex “Christian theological themes to itself,” resulting in the betrayal of the affirmations of the Declaration of Independence and “a counterfeit to the gospel of Christ.”

Lincoln was himself a child of Puritan upbringing, but his interpretation of American history came through what Robert Bellah has termed “civil religion” in the nation. American civil religion framed its beliefs from a religious (not necessarily biblical) canon of which the Declaration of Independence, the U.S. Constitution, the Bill of Rights, and Washington’s Farewell Address were a part. As his views about these documents matured, Lincoln’s public theology took shape.

The Dred Scott decision of the U.S. Supreme Court and the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 motivated Lincoln to resolve the injustice of slavery. He departed from the absolute certainty espoused by many supporters of “closed” exceptionalism that a mere mortal man could perfectly understand Divine Providence based on particular interpretations of various biblical texts with a direct application to the United States. Lincoln chose a different path.

Lincoln’s “new birth of freedom” removed the idea championed by O’Sullivan in his famous editorial of October 1840, where he stated “the voice of the people will be one with the voice of God.” Lincoln deconstructed biblical allegories and analogies between Old Testament Israel and the modern United States all while preserving the integrity of the Declaration’s focus on liberty and justice. He broadened the theological verbiage to underscore religious liberty as was first formally observed in James Madison’s “Memorial and Remonstrance Against Religious Assessments” (1785).

Lincoln’s genius was to retain Madison’s restraint to establish a certain religious sect (Christian or not) above another. He refused to enact domestic policy based on interpretations of biblical texts that were used to vehemently defend slavery as a divine institution. Lincoln believed unjust laws should be reversed and injustices corrected for all Americans to experience the full embrace of liberty. He would lead the nation through the bloodiest war in its history to bring it about.

The Return of Closed Exceptionalism

This understanding of American history is not well received by certain segments of organized Christianity in America. The latter half of the twentietn century has seen a rise in adherents of “closed” exceptionalism. Pointing to Patrick J. Buchanan’s 1992 “Culture War” speech at the Republican National Convention as a key indicator that closed exceptionalism might be on the march again in American political life, Wilsey examines some movements and texts within the right wing of modern American evangelicalism where “closed exceptionalism” is taught.

As a Southern Baptist, Wilsey maintains a thoughtful, but respectful approach to evaluating popular evangelical curricula. Examining the A Beka, Bob Jones University, and Veritas texts used by many Christian schools and homeschools across the nation, he found that each of the three texts “presented American history in closed exceptionalist terms.” He found that “each text was ethnohistorical, morally censorious (rather than morally reflective) and lacking in critical historical thinking.”

The American political tradition remains in flux as a new birth of theocentric politics has trumped what Wilsey would believe to be the necessary tension between patriotism and idolatry. He believes this is dangerous.

Faith As A Political Weapon

It is imperative to distinguish between the Christian gospel and the concept of national “chosenness” in closed American exceptionalism. The gospel and closed American exceptionalism are mutually exclusive. To accept the gospel is necessarily to reject closed American exceptionalism, not only because they are two different things, but because their objects of loyalty are two distinct entities in opposition to one another.

Wilsey believes a reorientation must take place that is as old as the nation itself. At its heart, theological foundations are critical to understanding the scope of American political philosophy. The American founders anticipated the factions that could easily form as a result of religious fervor and worked to pre-empt their widespread reach into the public square by making certain that laws were not passed restricting any establishment of religion or the free exercise thereof.

The effect of this law prevents personal faith from becoming a political weapon to be wielded by would-be charlatans and tyrants. The cultural influence of the church on society was to be free of government intrusion and authority. Likewise, religious liberty was to be the hallmark of the American government where all people could worship according to the dictates of their conscience.

The abiding quandary for Wilsey is whether modern American Christianity can evaluate the United States and its exceptional status in the world in light of theological precision so as to prohibit “well-meaning Christian people” from going down paths where the “potential for wrong in the name of right” transforms Christianity into mere politics.

If President Roosevelt was right, perhaps not.