Last week, the Wall Street Journal reported that at a recent security conference in Israel the head of the military showed the portraits of Englishman Mark Sykes and Frenchman François Georges-Picot. These are the diplomats whose secret Sykes-Picot Agreement during World War I guided the partition of the Ottoman Empire at the Paris Peace Conference in 1919 and established the boundaries for what would become Iraq, Syria, and the modern Middle East.

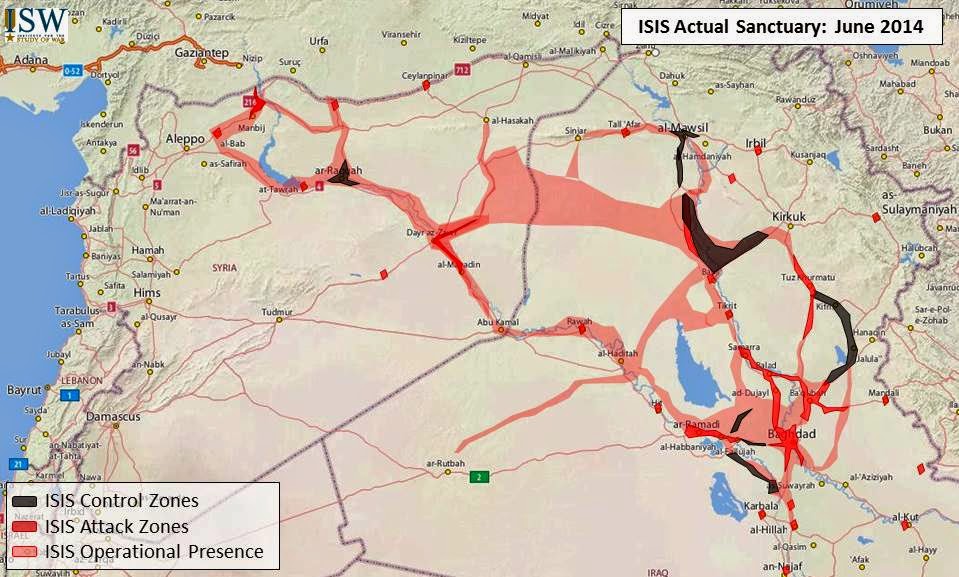

All of that is now coming apart. The fall of Mosul and the advance of ISIS—the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant, an al-Qaida offshoot—toward Baghdad last week prompted headlines warning that Islamist militants aim to redraw the map of the Middle East and establish a new state: a modern-day Islamic Caliphate spanning parts of Syria and Iraq.

They are well on their way. According to reports coming out of Iraq, the 300-mile Iraq-Syria border has all but ceased to exist, erased by a network of sanctuaries and ISIS-controlled territory that has enabled the militants to charge across the Sunni heartland of northern and western Iraq from their strongholds in Syria. Iran is reportedly sending in thousands of troops to support the Iraqi regime in Baghdad, and a full-blown civil war between Sunni and Shiite factions appears to be imminent.

The idea of redrawing the Mideast map is nothing new—after all, that’s what the 1916 Sykes-Picot Agreement was all about. A more recent effort came in 2006, when then-Senator Joe Biden proposed to split Iraq into three semi-autonomous regions—Kurdish, Sunni, and Shiite—with a central government in Baghdad. Biden hoped partition would prevent Iraq from falling into a civil war between Sunnis and Shiites, reasoning that because it was originally an “artificial” creation of Western European powers, Iraq could never become a stable nation without a Saddam-like dictatorship to hold it together—hence, it could never be a democracy. (Biden’s partition plan didn’t get far, and by 2010 he was boasting to Larry King that a unified, democratic Iraq would be “one of the great achievements of this administration.”)

Solving A Very Old Problem

The same might be said of Syria, whose protracted civil war has now undermined the country’s territorial integrity and enabled the rise of ISIS, thrusting the question of the Middle East map back into the limelight. But is this analysis correct? Are Iraq and Syria impossible to maintain as nation-states simply because they were created by European powers after WWI? The last hundred years suggests the answer is no—but also that major powers must simultaneously stabilize them and push their leaders toward democracy if the region is to avoid large-scale sectarian conflict.

Nevertheless, it now seems the Middle East created by Sykes-Picot is going to collapse because of what National Review Online’s Mario Loyola last week called the Obama administration’s “criminal negligence” in Iraq. If so, then we should at least pause to consider what it is that we’re allowing to slip away, and why it has held together for so long.

Sykes-Picot was partly about the imperial ambitions of a victorious France and Britain, but it was also a serious attempt to solve a very old problem. At least since the mid-19th century, the Ottoman Empire had been understood to be the “sick man of Europe,” a ramshackle power that was fatally weak; it was only a matter of time before it collapsed. What should replace the Ottoman system—which in earlier centuries had been an elaborate and fastidiously administered empire stretching from Budapest to Baghdad—was a serious concern for Britain and France in particular, not least because neither power wanted the other to seize the entire Middle East as an imperial possession. If nothing else, competition made them take the matter seriously.

When the Ottomans allied with Germany and Austria after the outbreak of the First World War, and especially after they lost, the question took on a new urgency. But unlike previous wars for empire, Allied territorial gains in WWI were held as “mandates” from the League of Nations rather than being annexed outright. In some ways, this was a mere formality that paid lip service to the idea the Allies were holding territories in trust for native inhabitants when in fact they were effectively ruling through client regimes.

On the other hand, Britain and France were stretched thin after WWI and looking for ways to pull back from imperial commitments they could no longer afford. The mandate system gave them a way to maintain their interests without expending treasure and blood on actual empire, while recognizing that in the long term, former Ottoman provinces would have to be governed by former Ottoman subjects in the form of modern nation-states.

From our perch in the 21st century, it’s easy to dismiss the Allies’ scheme to carve up the Ottoman Empire as nothing more than rank imperialist ambition—Europeans imposing their hegemony on a vanquished enemy they considered fundamentally inferior and incapable of self-government. And it’s true that the modern Middle East is a creation of the European victors of WWI. Iraq itself was the melding of three Ottoman provinces—Basra, Baghdad, and Mosul—which the British gave to Feisal Hussein as a consolation prize for the loss of Syria to the French (the Brits gave Jordan to Hussein’s brother, Abdullah, in an attempt to reconcile Britain’s conflicting promises to the Arabs and the Jews regarding the fate of Palestine).

So, yes, the Allies assumed responsibility for the fate of former Ottoman provinces after WWI, and at the time this served their imperial interests—to some extent. What Britain and France could not accept, however, was chaos in the Middle East or domination of the region by their rival, even if that meant assuming responsibilities they could ill-afford after the bloodletting of WWI. The Allies accepted, in other words, that if the Ottoman system were going to disappear then it would have to be replaced by something. The prevailing dominance of Wilsonian rhetoric at the Paris Peace Conference obliged the creation of nation-states—if at the time only nominal—whose integrity and stability were to be safeguarded by the Allied European powers. For France and Britain, this represented both a benefit of winning the war and also a burdensome and costly responsibility.

The underlying idea of post-WWI mandates in the Middle East—including the Anglo-Iraqi Treaty of 1922, which replaced the formal British Mandate for Mesopotamia under the Covenant of the League of Nations—was that established powers would ensure the territorial integrity and sovereignty of nascent powers until those regimes could stand on their own. In practice, it was imperfect; it was, in fact, badly abused. But it nevertheless represented the ideal of an international system of sovereign nations, the weakest and most insecure of which would be protected by the strongest and most stable.

That system, based on the Sykes-Picot Agreement, has more or less held the Middle East together for nearly a century, preventing the region from cracking up and descending into widespread civil and ethnic war. Last week, the system rapidly began to dissolve. In time, history may well judge that its dissolution was the direct result of negligence and inaction by the United States—whose de facto mandate over Iraq began with the fall of Saddam Hussein in 2003, and whose erstwhile leaders simply threw it away.

Follow John Davidson on Twitter.