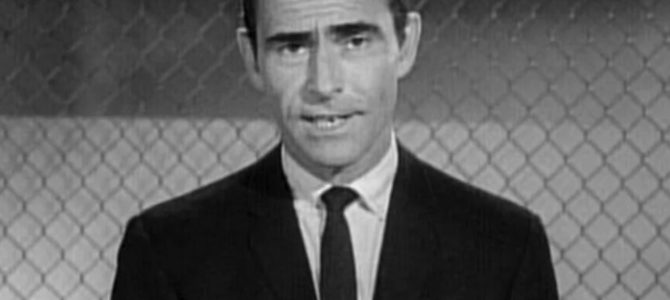

Once, when asked what Rod Serling’s legacy should be, the revered science fiction and horror writer Richard Matheson, who wrote several scripts for Serling’s “The Twilight Zone,” hoped it wouldn’t be based on that show.

Stephen King was more specific. Although King saw some quality in “The Twilight Zone,” he said it didn’t come from Serling’s “terrible” scripts.

In Nicholas Parisi’s new book, Rod Serling: His Life, Work, and Imagination, Parisi seems aware of Serling’s shortcomings in this regard, and as such, seeks to rescue his reputation. But he is rarely successful because his book is not a biography or literary criticism; instead it is largely a synopsis of Serling’s scripts.

He breezes past Serling’s biographical details. He notes how Serling’s service during World War II as a paratrooper in the Pacific informed his anti-war themes. But he doesn’t delve into the savagery of the clash between the suicide-happy Japanese and the shell-shocked American soldiers.

There is merit in arguing that Serling was a gifted writer. He wrote the script for the well-regarded 1964 film Seven Days in May, and co-wrote the sci-fi classic, The Planet of the Apes.

Parisi is at his best in settling the controversy over who really wrote the superb shooting-script for The Planet of the Apes. Some have credited this to the Academy Award-winning screenwriter Michael Wilson, particularly with regard to one of the most jolting endings in cinema history. That’s when Charlton Heston, convinced he has crash-landed on another planet where apes rule over primitive humans, discovers courtesy of a half-buried Statue of Liberty that he has returned to a nuclear-blasted earth.

Through impressive detective work, Parisi establishes that Serling deserved credit for the lion’s share of the shooting script, including the ending. But Parisi glosses over Serling’s equally impressive screenwriting achievement.

In 1964, Serling adapted Fletcher Knebel and Charles Bailey’s Seven Days in May. The book, as with the film, was politically charged pulp in which the military attempted to overthrow the U.S. government. Serling retained the book’s motivation for the attempted coup, stemming from an arms control agreement between a dovish president and the Soviet Union that the Pentagon believed jeopardized the country.

But he also sharpened the message of the novel with regard to how a military takeover violated the Constitution. He did so by having the whistleblower of the plot, a Marine played by Kirk Douglas, express opposition to the arms control agreement but also recognize that the president was commander-in-chief.

These two films, with their restrained political message, were an anomaly in Serling’s work, however. Serling was the worst kind of liberal — although, to his credit, Serling did try to slip the hot-button issue of racism past conservative and timid studio heads. But his desperation in getting his political message across was often heavy-handed and sacrificed entertainment value for smug preachiness. As King noted, Serling too transparently used watered-down supernatural themes as a means to address political issues.

Watching his early 1960s show, one would never guess that there was a Cold War between two powers, and how the nuclear holocaust he feared could have just easily come from outside the United States. The Soviet Union went unmentioned in Serling’s scripted shows. He was an early proponent of the “Blame America First” crowd that is a staple of the left today (the only time Serling ventured elsewhere to bash racism was Nazi Germany), focusing on America’s blemishes rather than the Soviet Union’s.

Such shortsightedness rendered his scripts hypocritical. The Soviet Union embodied all he railed against: anti-Semitic pogroms, police state tactics, and brutal put-downs on dissidents. Such a merging of Soviet totalitarianism with science fiction was possible, as George Orwell showed.

It is for this reason that the “Twilight Zone” was at its best when it didn’t deal with political issues. Arguably the most lauded episode, Richard Matheson’s “Nightmare at 20,000 Feet,” in which a recently released mental patient (played by William Shatner at his hammiest) is convinced that there was a monster on the wing of his passenger airplane, had no overt political message.

Serling was at his best when he adapted novels for movies. From this one could conclude that Serling worked best under some type of structure rather than having creative control. But Parisi doesn’t reach this conclusion. His book seems fixated on writing needless synopses of Serling’s “Twilight Zone” scripts.

To his credit, Serling posessed some self-awareness about the poor quality of his scripts, and he was clear-eyed and self-deprecating about his output. He recognized that the best writing for the “Twilight Zone” came from other writers.

By the 1970s, Serling was a prisoner of a show for which he produced no quality work. He spent his last years as a narrator for the mediocre “Night Gallery.” Serling deserves better than this, and hopefully another biographer will recognize his value and not focus almost exclusively on rehashing Serling’s “Twilight Zone” scripts.