It didn’t take long for the wheels to start coming off the wagon of St. Louis Circuit Attorney Kim Gardner’s prosecution of Missouri Gov. Eric Greitens.

An indictment with dubious origins and few facts has led to a trial with almost unbelievable moments of legal comedy. There was the initial hearing, when the prosecution admitted to the judge that they don’t have evidence to win the trial. Then there the moment when the prosecutors had to tell the defense that they didn’t have the photo that is supposedly the reason for the indictment in the first place.

And last, but most certainly not least, there was the moment when the prosecution allegedly broke the law by bringing on a prosecutor who was serving elsewhere as a criminal defense attorney. Yep, that’s a crime in the state of Missouri, and the prosecution allegedly committed it. Whoops.

It’s been my experience, after decades in law enforcement, that prosecutors tend to know the difference between what is and is not a crime. Most of the time, that is. In the case of Kim Gardner, I’ll admit: I’m not sure she does. Because in her action against Greitens, she appears to have missed the boat on what a crime is. In this case, she has no victim, very little evidence, no legal standing — and given all that, almost no hope of conviction. The slipshod work by the prosecution led one high-level member of law enforcement in the state of Missouri to call this “a clown show prosecution,” and that opinion is widely shared in legal and law enforcement circles in Missouri.

Obviously, Gardner probably didn’t think it would go this way. She was probably thinking this case against a high-profile, popular, sitting Republican Governor would make her name. Now it might ruin her career. Here’s why: It’s almost certain, at this point, that the case will either be thrown out by the judge or that the governor will be found innocent. But there might be more fallout to come — for Gardner, that is. What if the Greitens team files a civil suit against Gardner, one that could cost her millions in damages? What if citizens in the city of St. Louis file complaints with the police or Missouri’s attorney general about Gardner’s conduct, leading to a criminal investigation? Ironically, a case that began on illegitimate grounds could end with the quite-legitimate investigation of the prosecutor who started it.

Five new facts have emerged in the course of the trial that point to this being a real possibility. Together, they tell the story of a seemingly malicious and reckless prosecution driven by politics, ignorance, and ego, rather than a pursuit of justice.

1. It appears that Gardner began preparing the paperwork for the indictment prior to conducting any investigation.

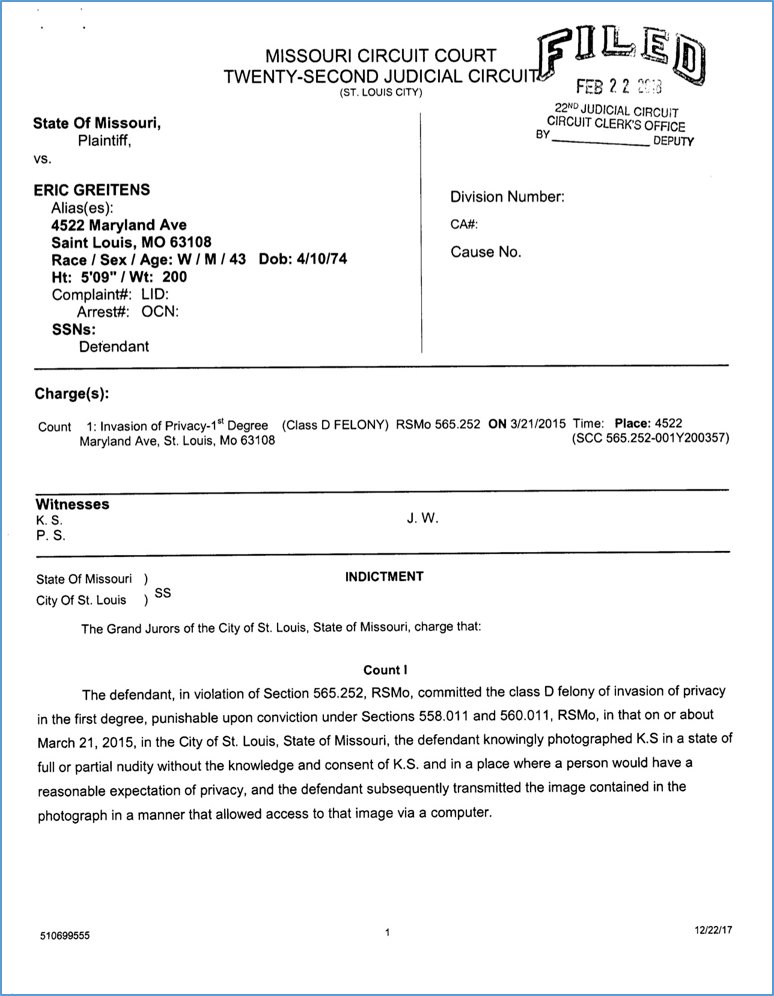

Take a look at the bottom right hand corner of the indictment Gardner filed in this case. Notice the date: 12/22/2017.

That appears to be the date on which this document was first created. And it’s an interesting timestamp. Why? Because according to a letter released by the circuit attorney’s office, Gardner did not launch her investigation of Greitens until Jan. 11, 2018.

That means the indictment paperwork was apparently begun by the circuit attorney’s office a full 20 days before that office publicly became involved in this case. In other words, Gardner (or someone on her team) began writing out an indictment document before evidence of a crime was ever brought forward, before her office conducted any kind of inquiry, and before a grand jury ever sat. You don’t need a law degree to be bothered by this: Why would you prepare an indictment about a crime weeks before investigating that crime?

Answer: You wouldn’t. Unless of course the evidence didn’t matter to you, because you were just looking for any crime that fit and any jury that would indict.

Now, Gardner might claim this date screwup was a simple administrative oversight, a mere clerical error. If that’s the case, it’s just as troubling: Who makes mistakes like that when they charge a sitting governor with a felony? Did Gardner’s office just boot up a computer and decide to grab whatever indictment popped up most recently? And why not double-check a document like that before submitting it? What other “mistakes” of this kind have been made during the course of her investigation and indictment? Or worse: What mistakes has Gardner made prosecuting other cases, where the stakes for the people involved are just as significant?

Getting an explanation for this “12/22/2017” date is important. It seems Gardner was either plotting this indictment since late December, prior to gathering any evidence, or she and her team have been careless, reckless, and flippant about the documents and procedures involved in something as serious as charging the state’s leading official with a crime. Either possibility is damning.

2. Gardner allegedly broke the law in the course of her prosecution.

According to Missouri law, a prosecutor in the state cannot also serve as a criminal defense attorney. It’s a section of the law that Gardner would have done well to read twice before inviting Professor Ronald Sullivan of Harvard University to join her prosecutorial team. Greitens’ lawyers allege in a motion to disqualify Sullivan that when she offered, and he signed, a $12,000 per month contract to join her prosecution team, Sullivan committed a misdemeanor offense — and Gardner became party to a crime.

Gardner’s spokeswoman has rejected the allegation, claiming it’s legal because Sullivan does not have any pending litigation against the state of Missouri, but there’s really very little room for gray area here: Sullivan allegedly committed a crime, and his boss, Gardner, likely should have known better. She’s a prosecutor, one of the leading law enforcement officials in the city of St. Louis.

There’s another issue with the hiring of Sullivan to assist the prosecution, according to the motion filed by Greitens’ lawyers. They claim the deal Sullivan struck with Gardner allows him to hire whoever he wants to assist him, and that those people can be paid for with private funds. The way Gardner set this up, Greitens’ political opponents can apparently pay to prosecute him. In other words, the contract between Gardner and Sullivan essentially “privatizes” prosecution. We now have a bizarre case of what appears to be a weaponized and privatized prosecutor, a potential abuse of authority that should deeply concern all citizens.

There is a reason Missouri doesn’t allow this kind of thing: because it’s flat-out wrong. Our system of justice depends on public prosecutors, paid for by public funds, with their work, their methods, their sources, and their funding made public for all to see. The fact that Sullivan was apparently given such wide latitude to use private money to assist the prosecution — and the fact that he was brought aboard in the first place — represents a threat to the legitimacy of the judicial system.

3. Gardner’s assistant prosecutor allegedly misled the grand jury about the indictment.

Already in this case, the prosecution has struggled to show evidence of a crime. They have to depend on the testimony of an aggrieved ex-husband and a copy of a secretly recorded audio tape that ex-husband made — a taping done without the alleged victim’s consent or knowledge. That’s basically all they’ve got.

And that might explain why, during the grand jury proceedings, Gardner’s assistant prosecutor, Robert Steele, allegedly misled the grand jury to get them to indict the governor. That’s right: He gave a “false and misleading” statement about the statute the governor is alleged to have violated, according to Greitens’ defense lawyers. And he allegedly gave it in order to make the grand jury believe that a crime had been committed.

The defense’s opening two sentences in a recent motion make it plain what can happen if a prosecutor gives a misleading statement to a grand jury: “There are only a few actions by a prosecutor in presenting her case to a grand jury which can result in dismissal of the indictment. Offering misleading legal instructions is one of them.”

4. Gardner’s investigators were under FBI investigation.

A note to prosecutors: Beware the company you keep.

In my prior piece about this case, I covered the utter strangeness of a prosecutor using out-of-state private investigators to conduct an investigation of a public official. As it turns out, I was only scratching the surface. The out-of-state private investigators Gardner hired were led by a man who was once under FBI investigation himself. You couldn’t make this up if you tried: The private investigator, William Don Tisaby, worked for the FBI when he was accused of bigamy, and what’s worse, he allegedly lied to the FBI about it.

It was already odd to have a private investigative firm looking into a governor. Their work, as has been reported, was sloppy and irregular for a case like this. They weren’t allowed to write down any of the facts they found, and they were paid sums of money well above-and-beyond what a police officer would make for the same work. Now you add to that the fact that the investigators were being investigated, and you have another supporting fact for the countersuit that could await Gardner at the conclusion of this case.

5. Even the chief of police of St. Louis is demanding answers.

Another tip for prosecutors: Don’t pick a fight with the people who arrest the criminals you’re supposed to prosecute.

Gardner has developed a negative reputation among police officers in St. Louis. She’s looked the other way on cases into which they’ve poured time and energy; and she’s gone after police officers with more aggressiveness than she’s gone after killers and thieves.

That might explain why the new police chief in St. Louis, John Hayden, was so quick to point out to the press that the police had no involvement in the Greitens case. Not only did they not investigate, but the chief took issue with Gardner’s suggestion that the police had been asked to and didn’t: “It makes me frustrated because it’s as if she’s saying I failed to do something I’m supposed to do here, and that’s not the case at all. To date, nobody has tried to report this to the police department.”

Hayden went further and asked for answers, specifically why private investigators would be brought in to do an investigation given his police department’s decades-long history of, you know, conducting investigations. As Hayden put it, “This has all been oddly done to me as far as I’m concerned. She has to explain why she did what she did.”

Chief, when you said that, you could have been speaking for all St. Louisans — and indeed, all Missourians.

The Endgame

When prosecutions like this fall apart, they don’t go quietly. It is very possible that Kim Gardner will not only lose this trial, but that the process by which this case was handled will prove a case study in how not to prosecute someone. She could lose her bar license, and it is possible that a countersuit by the governor and his defense team would lead to millions in damages and fines. If the police or FBI or US attorney begin looking at her conduct in this case, she could even end up serving time herself.

Because of the stakes, here is how I suspect this will play out: The prosecution will get desperate. They will start grasping at anything, any shred of an attack on the governor, the better with which to support their failing case. So don’t be surprised if they begin to poison the well in the press, even more than they already have. They may make more outlandish claims about what the governor did or did not do to the alleged victim. They may even try to indict the governor on some other charge, as a way of distracting the public from the flimsiness of the first one. Already subpoenas have been issued from Gardner’s office on matters unrelated to the first indictment. Another ludicrous indictment is likely to come for a prosecutor who needs to dig her way out of the hole she made.

A story making the rounds in St. Louis police circles speaks to just how far the prosecution is willing to go now that their core case has begun to fall apart. As word has it, on Tuesday of this week, Gardner invited someone she knew from her school days over to her office. The gentleman was a cop. She told him to come to her office, a chance for old friends to catch up.

When he came into the office, he was brought in to sit with Gardner — and with the lead investigator on the Greitens case, William Tisaby. Quickly, Gardner and Tisaby began pressing the cop for details on the security procedures at the Chase Park Plaza hotel, where the woman who the governor had the affair with worked. Were there tapes available of people’s comings and goings in the hotel that they could get their hands on?

The cop was, correctly, bothered by their questions. This wasn’t why he had come to her office. He asked if he needed to bring in his department representation. Presumably he knew, as the police chief himself stated, that the police were not involved in this case. He told them nothing. Sensing that her “source” was not going to cooperate, Gardner is said to have excused herself, and the meeting ended.

That story reveals the great lengths to which the circuit attorney may be having to go to find evidence: deceiving police officers in order to get help in her investigation that appears to be falling apart. And, perhaps worst of all, she’s said to be wasting a cop’s time by involving him in a case about the personal lives of private citizens (the governor was a private citizen when all this took place). St. Louis had one of its bloodiest weekends in a long time just this past weekend. And our circuit attorney is said to be busy asking about hotel rooms at the Chase Park Plaza.

But we now have ample evidence to suggest this is just how Gardner does business. And if she sees the inside of a jail cell or watches her bank account go to zero because of her actions against the governor, then she will simply reap what she has sowed — and what many in law enforcement believe she has deserved since her earliest days as circuit attorney.