Before each high school dance, my husband and I must participate in an unnerving and relatively new phenomenon: The pre-dance picture party. One brave family (usually us) offers to host my daughter’s large circle of friends and their parents for an extended photo shoot to capture the big night. Both moms and dads — even siblings — are expected to attend, dedicating a chunk of their Saturday night to participate in the festivities.

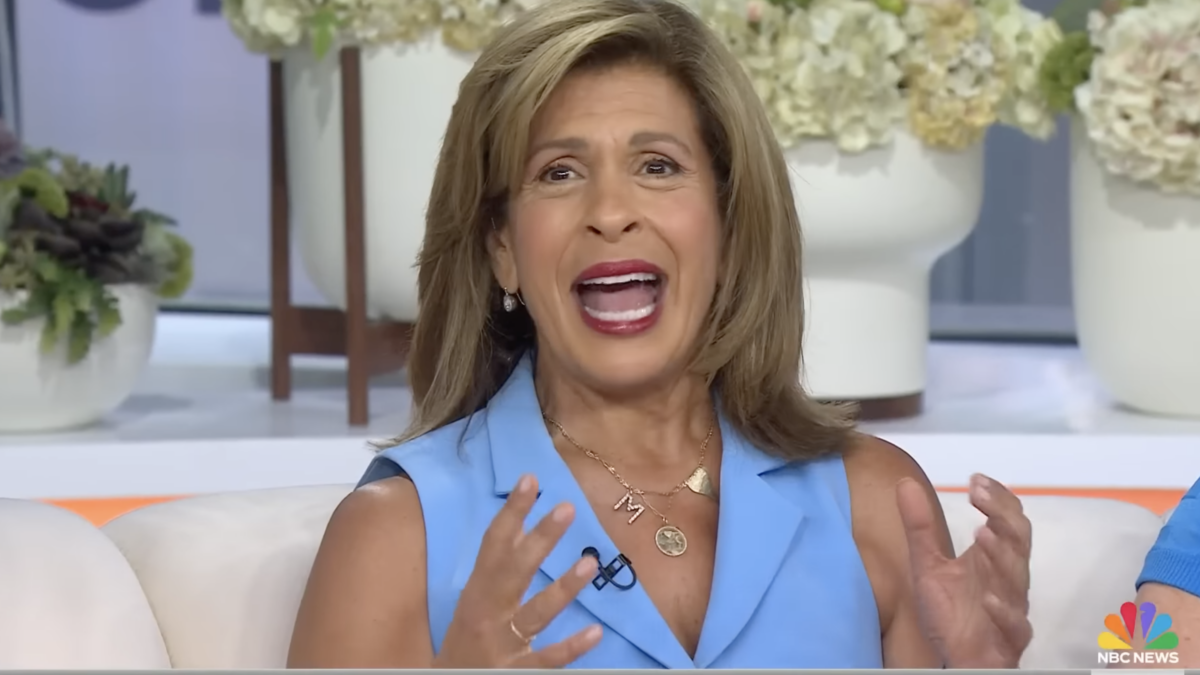

We’ve had upwards of 50 people in our house, served food and drinks, and watched parents wielding high-powered digital cameras take loads of pictures before the teens head out. It’s like a red-carpet event where our daughters are the celebrities. The moms promptly post a collage on Facebook, adding to a lengthy thread of photographed moments that catalog their child’s life. The photos are then loaded onto computers for safekeeping.

The picture party circus is unlike anything my parents would have tolerated, let alone participated in, and it’s just one example of how technology has fueled the child-centered world that we, as parents, have created. It’s hard to imagine such a scrum would exist but for social media and weaponized cameras. While we lament how much our teens are addicted to technology — giving rise to an alarming epidemic of narcissism, insularity, and indifference among our nation’s youth — we have yet to really look at how our own use of technology has fostered this.

That’s one angle in a new episode of Netflix’s “Black Mirror,” which gives a glimpse into where the trajectory of emerging technology and parenting could potentially collide. In “Arkangel,” directed by Jodie Foster, a single mother raising her only child in a working-class neighborhood has an implant inserted into the brain of her three-year-old daughter after she goes missing from a local park for a brief time.

The implant allows the mother, Marie, to track the whereabouts of her daughter, Sarah, on a computerized tablet. Apps on the tablet enable Marie to blur out violent images that Sarah might see on television and prevent the girl from seeing real-life threats like an aggressive dog, schoolyard bully or even her ill grandfather. Marie can watch everything that’s happening to Sarah in real-time, even monitor her physical health. Every moment is saved on the tablet, and Marie dutifully checks the device throughout the day to make sure Sarah is safe.

When the girl reaches grade school, she’s mocked by classmates for her robotic personality. Out of curiosity, Sarah starts to ask them questions. After a boy asks her if she’s ever seen blood before (she hasn’t), then tries to describe it to her, Sarah goes home and stabs herself with a pencil to draw blood. Marie, alarmed at what she’s done to her daughter, packs away the tablet.

Several years later, when Marie discovers teenage-Sarah lied to her about where she was going one evening, Marie retrieves the tablet. She’s shocked to watch Sarah lose her virginity and experiment with drugs. After a series of incidents, Sarah realizes her mother is again using the tablet, and in the ultimate “Twilight Zone” twist, she beats her mother with the tablet until it shatters, then runs away. The last scene is Sarah hitchhiking and getting into a trailer truck, unbeknownst to her desperate, battered mother, whose good intentions ultimately backfire.

The episode is generating plenty of chatter; most of the discussion focuses on where technology is headed, and how it will appeal to our most basic instinct as parents — to protect our child — and consequently impair their ability to deal with real-life situations that are sad, scary, and discomfiting. While it’s not unrealistic to expect this type of “brain-implant” oversight in the future, to some extent, it’s already here.

Technology now empowers us to micro-manage our children into, and sometimes beyond, adulthood, with tools that parents even a decade ago didn’t possess. We can track our teenager’s location on their cell phone to make sure they are precisely where they’re supposed to be. We can email teachers and coaches, helping our kids avoid having uncomfortable conversations about a grade or a coaching decision. We can check test scores and grades on school websites daily. We can guide every step of the online college application process, edit (or write) their essays, and basically speak for them without admissions officials even knowing it.

We can text and Facetime our teens whenever we want. (I know mothers who text their kids who are in college to make sure they’re up for class, or ask what grade they got on an exam.) Every birthday, vacation, athletic achievement, college acceptance letter, and yes, high school dance, is commemorated on social media, accompanied by glowing comments: good experiences are celebrated, bad ones are ignored. The adult’s life revolves around the teen’s schedule, which is meticulously managed on synched, cell phone calendars. While we blame technology for the self-centeredness and disconnect we see in our children, aren’t we ultimately to blame?

Which leads to one aspect of the episode that has been overlooked: Marie has no interests outside of her child. Obsessed with shaping her daughter’s life experience, she doesn’t have a social life or a boyfriend. She works outside of the home, but returns promptly each night to care for Sarah. When Sarah is a teenager, she teases her mom about never having a date or knowing how to have fun. The child is Marie’s only joy and purpose. In fact, when she catches Sarah having sex and using drugs, she confronts the boy, not her own child, and blames him for her daughter’s choices. Sarah is not an individual, she’s merely an extension of Marie, so surely any bad decisions must be someone else’s fault. I see this to some degree quite a bit in real life.

So, how do we resist the temptation to use the present-day version of Sarah’s brain implant? There are no easy answers. Controlling what your child sees — particularly on social media — is easy until they hit junior high. After that, it’s like whack-a-mole. They are very industrious when it comes to creating accounts, using other kids’ devices, hiding apps from you. Trust me, I’ve experienced it all. Once they hit high school, forget it. And whether you choose to track your teen’s whereabouts on her phone is your own judgment call. (I do not. I know for a fact my daughter will occasionally be somewhere she’s not supposed to be.)

But that only addresses one part of the bigger problem: The child-centric world we have created. Finding a balance between protecting your child and ostensibly living their life for them, making all their decisions, supplanting their role in important human relationships, giving them a false sense of importance, is more challenging than controlling a few iPhone apps. That’s the real parenting challenge both now and in the future.