Earlier this month, the Supreme Court heard arguments in Gill v. Whitford, a case about gerrymandering in Wisconsin. The topic of gerrymandering has been around for as long as there have been legislatures, and not just in the United States. Good government crusaders have always lamented that politics gets so political (which usually means that they dislike the results,) and this is especially true these days in gerrymandering.

What has changed lately is that, instead of trying to win over the voters, the losers of political fights now declare the game is rigged and plead for courts to grant them the victory they could not achieve on Election Day. Suits like this one have attempted to entangle the federal courts in redistricting decisions and, in Gill, Wisconsin Democrats hope they will at last get their way.

What courts should remember is that the gerrymandering fight is not new, nor are the circumstances now so different from those that have existed since the republic’s early days. The answer then, as now, was that gerrymandering cannot defeat a public sufficiently aroused against it.

Moreover, the more extreme the gerrymander, the more likely it is to crumble and even to benefit the other party. The courts need never get involved in a political gerrymandering fight because gerrymanders are inherently self-defeating.

Stretched to the Breaking Point

For an example of how this works, let’s look back to last decade’s congressional districts in a state that is widely reviled by reformers obsessed with gerrymandering: Pennsylvania. In 1994, Republicans won complete control of the Pennsylvania state government and maintained that hold, if narrowly, through the 2000 elections. This let the GOP guide the redistricting process that followed the 2000 census, when Pennsylvania lost two seats in the federal House, dropping from 21 to 19.

At the time the lines were drawn, Republicans held 11 of the state’s 21 House seats. They sought to increase that advantage through the arcane arts of redistricting. While maintaining the two majority-minority seats demanded by the Voting Rights Act, the legislature worked to squeeze Democrats every other way they could.

In two instances, two Democratic found their homes redrawn into the same districts. In another part of the state, a new district was designed so that it would be easy for a Republican state legislator to win.

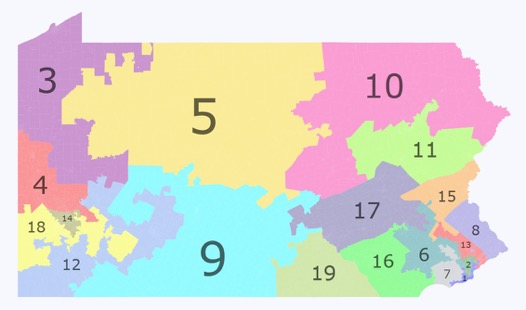

These were age-old tactics, helped by advances in computer-aided map-making. They came up with this map:

This was done, as in all such cases, through “packing” and “cracking.” “Packing” entails drawing a district that is heavily populated by the other party—in this case, Democrats. The 1st, 2nd, 13th, and 14th districts were examples of packed districts. They took advantage of areas that were already heavily Democratic—the cities of Philadelphia and Pittsburgh—and added nearby areas that were also light on Republicans. Packing is an effective technique, and is helped by the geographic self-selection common to cities, where lefties move in and righties move out.

The remaining Democrats in the state were “cracked”; that is, they were distributed among the other districts in such a way that they were never going to add up to a majority there. Democrats in the Reading area, for example, were disbursed among the 6th, 16th, and 17th districts in an attempt to defeat the Democratic incumbent there, Tim Holden. Similarly, the 10th and 11th districts divided between them the northeastern Pennsylvania Democrats in Scranton and Wilkes-Barre.

Cracking is less effective than packing. In the first example, Holden managed to eke out a narrow 51 percent victory in the new 17th district and remained in Congress for another 10 years. Likewise, the 11th district remained Democratic despite a lively challenge by Hazleton mayor Lou Barletta (Barletta eventually won the district in 2010, the last election before the next round of redistricting.) But in large part, the tactic worked: in the 2002 elections, they added one House seat and the Democrats lost three, making for a 12-7 GOP majority in the state’s House delegation.

A victory for the nefarious forces of gerrymandering? Yes and no. For one thing, the Republicans actually won a substantial majority of the statewide House vote in 2002: 56 percent. That they won 63 percent of the seats is a slight amplification of their statewide win, but of the sort that could happen even with less eccentric district lines.

Another problem for the GOP was that their victory was fleeting. In 2006, the midterm elections went against them and Democrats won 11 of the 19 seats. In 2008, Democrats picked up a 12th seat, completely reversing the intent of the state legislature’s line-drawing. What’s more, they did so with just 55 percent of the statewide vote, even less than what it took the Republicans to win 12 seats using a map they themselves designed. All the work of the post-2000 gerrymandering was undone by the same method that upsets many politicians’ plans: the people voted a different way.

The Rigged System Unrigs Itself

What went wrong? The Republicans overreached. They yielded to the temptation to crack the Democrats outside the two major cities into so many districts that they were left with slim majorities for all of the seats intended to be won by Republicans. In a way, they cracked too well. Because of the winner-take-all system, it was easy to convince themselves that a bunch of districts with 51 percent majorities were better than slightly fewer districts with somewhat larger majorities. That is true, but only as long as there is no national wave toward the other party. If there was, it would only take a shift of one or two percent of the voters to overturn the whole plan.

That is what happened in 2006. In a midterm election against an unpopular president, just enough voters shifted to the Democratic column in the 4th, 7th, 8th, and 10th districts to unseat all of their Republican incumbents. They came within 1 percent of taking another, the 6th. In 2008, the Democrats continued to hold those seats and picked up another in the 3rd as Barack Obama carried the state with considerable coattails. Democrats won all of these new seats with majorities of 57 percent or less. The Republicans had cracked themselves.

This pattern held across the country as Democrats stacked up huge majorities in the House—the majorities that brought us Obamacare. The results show that gerrymanders will always fail because the politicians always sacrifice long-term stability for short-term satisfaction. The post-2000 lines worked in Pennsylvania, but only for a snapshot of the state taken in 2002. By 2006, things had changed. New issues motivated voters. Party loyalties wavered. The “rigged” system had somehow unrigged itself and turned against the politicians who built it.

Sixty Percent of the Time, It Works Every Time

There is no permanent victory to be found in gerrymandering, and no court intervention is needed to replace the will of the people. The way the Pennsylvania Republicans of 2001 laid the seeds for their future defeat is just one example of our system using politicians’ ambition to defeat them. But this should come as no surprise. The entire system of checks and balances, of branches of government working against each other and guarding their own power: all of it is by design. That and the frequent election of House members ensures that no plan can succeed if the people do not cooperate. Politicians’ greed for just one more GOP seat led them to stretch things so far that it all snapped and crumbled. This will always happen, because greed and ambition are a part of who we are, and a part of our undoing.

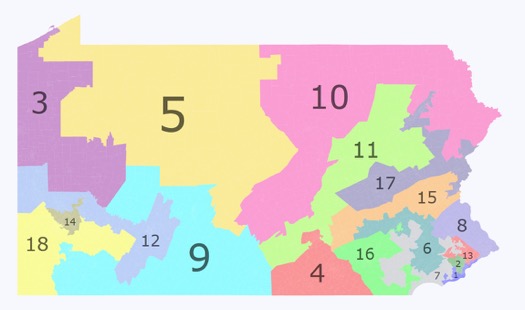

Both parties know this, and both refuse to learn from it. After the 2010 census, Pennsylvania Republicans doubled down on their strategy of 10 years earlier. After that census, which saw the state lose another House seat, the GOP legislature stretched the lines even further and came up with this map:

The 2010 election, the last one under the old districts, had seen the map flip back to 12-7 Republican as the party won the statewide House vote. As the state legislature embarked on the new map in 2011, they could see that in the five elections held under the old map, the extreme gerrymandering only worked in three of them. In the other two, it actually helped the Democrats. As Paul Rudd’s “Anchorman” character might say, “sixty percent of the time, it works every time.” Nevertheless, their ambition led them to this new map, even more convoluted than the last.

Why Even Bother With Gerrymandering?

So far, it has worked. In 2012, 2014, and 2016, the Pennsylvania House delegation has consisted of 13 Republicans and 5 Democrats. But none of those were particularly bad years for Republicans nationally, either. People with short memories will see this pattern and declare the system has been rigged again. Anyone with an eye on the national scene can also see that a repeat of the 2006 midterms could be coming in 2018. Five of the Republican House members won less than 59 percent of the vote in 2016, which was a favorable year for them as Donald Trump and Senator Pat Toomey won statewide races for the GOP. In 2018, they face an unpopular incumbent Republican President and a popular Democratic Senator up for re-election. We will find out in November whether the Pennsylvania GOP will be hoisted on their own petard again.

The main argument in Gill v. Whitford was based on an efficiency gap, an argument that the statewide percent of the vote for each party should equal the percentage of seats they win. But as we have seen in the case of the Pennsylvania gerrymanders, the more extreme gerrymanders work both ways (and politicians can’t resist the more extreme ones). Look at the statewide results of the two-party vote versus the seats won in Pennsylvania since 2002:

| Year | Percent R vote | Percent R seats |

| 2002 | 57.14% | 63.16% |

| 2004 | 50.60% | 63.16% |

| 2006 | 43.73% | 42.11% |

| 2008 | 43.99% | 36.84% |

| 2010 | 51.94% | 63.16% |

| 2012 | 49.24% | 72.22% |

| 2014 | 55.54% | 72.22% |

| 2016 | 54.06% | 72.22% |

In only one of those eight elections did Republicans lose the statewide House vote but win a majority of the seats. In four years, they won the statewide vote and won an even larger percentage of seats, but in two years they lost the statewide vote and lost an even larger percentage of seats. If efficiency gap experts looked at the Pennsylvania map in 2006 and 2008, they would pronounce it clear evidence of a Democratic gerrymander!

That gerrymanders are self-defeating is evident. They are based on a snapshot of an ever-changing electorate. Political events over which the map-drafters have no control will undo their work as often as not. When those events occur, as they inevitably do, the tightly stretched, finely cracked districts will collapse under their own weight. Gerrymanderers create what anti-gerrymanderers claim to want: swing districts that respond to changes in the political climate. They do so with what they think is a thumb on the scale to help their side, but events overtake them. Eventually, gerrymandering fixes itself.