It was bound to happen. Beloved and lauded as it is, the hit Broadway musical “Hamilton” is being taken to task as problematic by social justice warriors in the academy and beyond. This is another of example of how, culturally, we just can’t have nice things. Works of art must not merely be entertaining and insightful, they must be constantly investigated and interrogated to find the ways they cross the boundaries of political correctness.

In Slate, Rebecca Onion interviewed historian Lyra Monteiro about her essay, “Race-Conscious Casting and the Erasure of the Black Past in Lin-Manuel Miranda’s Hamilton.” A quote from the conversation perfectly illustrates this modern penchant for holding art to unattainable standards of race consciousness. Asked if she has received any negative feedback on her article, Monteiro says:

I honestly haven’t heard from anyone who says something negative about the article. I think enough people today are exposed to the idea that all your faves are problematic, that there’s no such thing as pop culture that isn’t biased and hugely problematic in all kinds of ways. So I think that helps. I have a good friend who’s a huge fan of the musical who has not mentioned this article to me, though I know she’s read it! I think that’s partially because she doesn’t know what to say because she loves it so much.

Before tackling Monteiro’s actual criticisms of Lin-Manuel Miranda and his musical, let’s unpack this statement a bit. First of all, the central idea here is that everything is problematic. If we look closely enough, we will find the scourge of racism and sexism in every work of art, and we should. It is irresponsible to create or consume art without constantly viewing it through this prism of oppression.

Secondly, it could be that Monteiro’s friend hasn’t criticized her article because she is somewhat afraid to. If the basic premise under which we are operating is that “everything is problematic (a polite way of saying racist),” then to defend a work of art against those charges is in itself to aid and abet in that racism. So broadly is that view held by liberals in arts and education that it is left to conservatives to defend art from these spurious accusations.

‘Hamilton’ Is Art, not History

The first thing that has to be understood is that “Hamilton” is a work of art, not a work of history. The very best you can hope for from historical art is that it will develop a framework and spur an interest in a subject that leads audiences to deeper learning. Miranda worked with Alexander Hamilton biographer Ron Chernow to ensure historical accuracy, but in crafting a theater piece such accuracy is but one of many concerns. The primary job of a Broadway musical is to entertain, not to educate or revise the standard historical record.

But even Monteiro’s historical criticisms don’t pass muster. For instance, she argues there is no evidence that Hamilton was, as Miranda and most historians agree, truly anti-slavery. His wife’s family had slaves, she argues, and he would have benefited from their general presence in the economy. In so arguing, Monteiro downplays Hamilton’s work with the New York Manumission Society. In his newsletter The Transom, Ben Domenech points out how unfair this is to Hamilton and his memory:

The society organized, advocated, boycotted, and worked in spite of political pressure in the opposite direction to achieve the liberation of slaves and eventual abolition of slavery. Hamilton’s initial act as a member was to push for a requirement that all members liberate their slaves. It is of course possible to argue Hamilton’s motivations for participation were Machiavellian, as so many of his stances were, but to suggest that (Historian) Rick Brookhiser needs to prove something that is so widely accepted as historical fact is just ridiculous. Here’s a hint: When the founding member of an organization (John Jay) signs that organization’s top priority into law as the state’s governor, the organization might’ve had a little bit to do with it. Politics – how does it work?

In Defense of ‘Founders Chic’

One of the principal foundations for Monteiro’s criticism of “Hamilton” is that it employs a technique called “Founders Chic.” The idea was invented by H.W. Brands, in a 2003 article of the same name in The Atlantic. Basically, it argues that historians overpraise the good nature of the Founding Fathers while downplaying their connections to slavery, misogyny, abuse of Native Americans, etc. In Monteiro’s view, “Hamilton” is guilty of this white male hero worship.

Broadly speaking, it is for the best that historians take a levelheaded view of historical figures. George Washington could and did tell lies. But more is being asked here. Monteiro is demanding that Miranda and historians subsume the very actions that led to the veneration of a white historical figure to that figure’s failures to live up to modern codes of identity politics.

This is a historical test that no white person from the federal period could ever possibly pass. In fact, it is only because he was a product of his time that Hamilton’s work for the furtherance of democracy and abolition are remarkable. This is not to suggest that we make out of Hamilton an alabaster statue of perfect goodness, and clearly that’s not what Miranda has done. But the teaching of early American history must be more than an exercise in knocking rich, white dudes down a peg.

Miranda Isn’t Erasing the Black Past

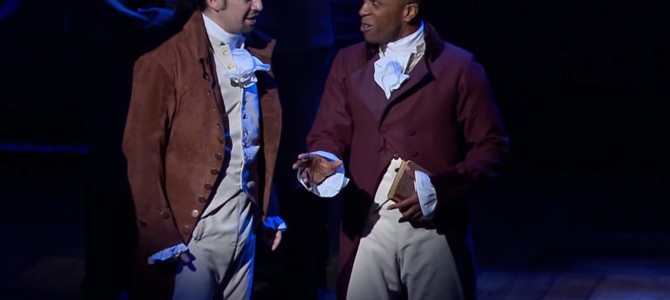

Monteiro’s most strident criticism of Miranda’s musical is that he erases the black past. This might seem odd, given that almost everyone on stage is either black or a person of color. The problem is that everyone in this diverse and gifted cast is playing a white historical character. Miranda stands accused of engaging in a kind of historical blackface. He is inviting people of color to see themselves in the men who founded our nation, but like everything else this is problematic.

Monteiro would prefer that Miranda had peopled his play with some historical black characters, so as not to give the impression that federal-period America was all-white. She even goes so far to suggest that, had Miranda worked with a historian of color rather than Chernow, we would see these black historical figures represented.

Setting aside the fact that it was Chernow’s book that inspired the musical, this is a bizarre suggestion. The assumption that a minority historian would stress minority participation while a white historian would ignore it is baseless. The simple fact is that the people in power, who are Miranda’s subjects, were white men. A social historian, of any race, might suggest a broader representation of people not in power to put the events in context. But that would depend on his view of history, not the color of his skin.

Ironically, Monteiro is calling for in “Hamilton” a kind of character with a long and very problematic history in theater. She wants some magical Negroes. Her suggestion is that Miranda should have given life to some of the slaves who worked in the fancy houses depicted in the play. But what could that have resulted in, other than the classic, often offensive trope of the poor, oppressed black man who with his keen, inherent common sense teaches the white people important lessons? Miranda is far too gifted a playwright and too astute a student of theater to fall into such a disastrous trap.

A big part of what has made “Hamilton” such a phenomenal success is that it has great appeal for people all over the political spectrum. For a work steeped in history and politics in this day and age, that is a remarkable feat. Liberals love the diversity of the cast, the translation of American history into the idiom of hip-hop, and the careful repudiation of the period’s racism and sexism. Conservatives cheer that the recently much-maligned Founding Fathers are being presented positively, not first and foremost bathed in guilt.

What Monteiro is asking for would undermine the balance that Miranda has so brilliantly crafted. Indeed it would turn the play into just another festival of grievance. Frankly, there is plenty of that in modern theater already. “Hamilton” is a work of art uniquely able to bring the citizens of our nation together. That is something to be celebrated, not to be criticized as a whitewashing of our common historical legacy.