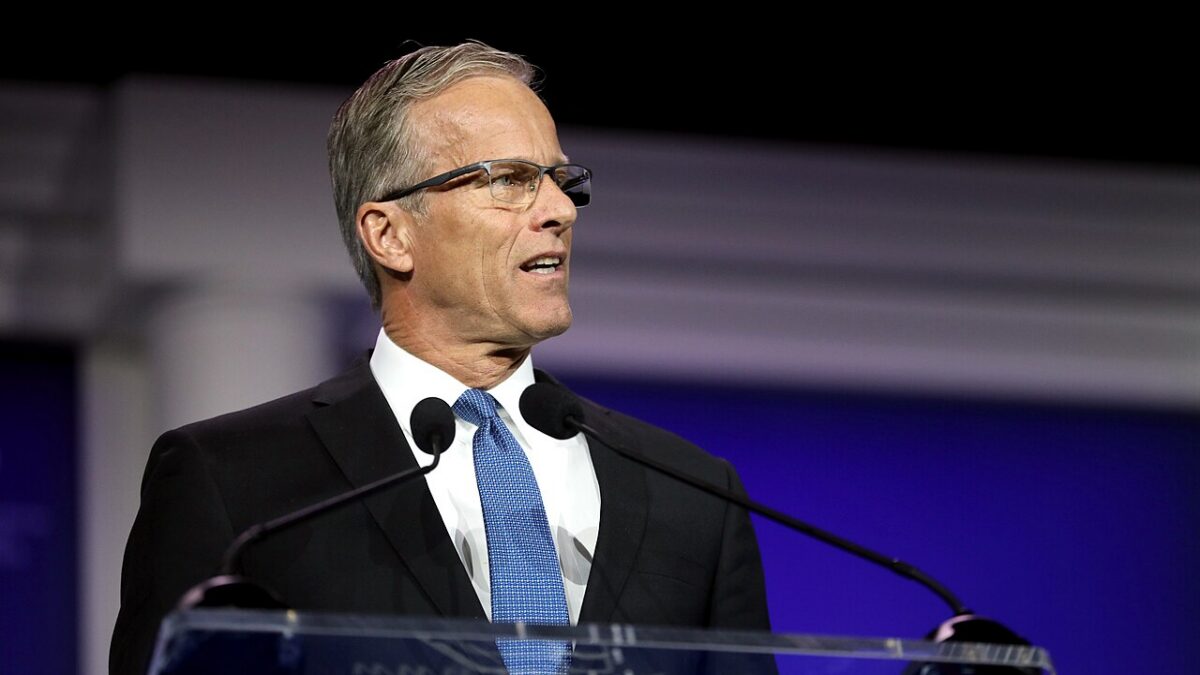

After the North Carolina House of Representatives passed a bill allowing magistrates and clerks to recuse themselves from performing all marriages due to religious objections to same-sex marriage, Republican Gov. Pat McCrory vetoed it, claiming to defend the Constitution.

“I recognize that for many North Carolinians, including myself, opinions on same-sex marriage come from sincerely held religious beliefs that marriage is between a man and a woman. However, we are a nation and a state of laws. Whether it is the president, governor, mayor, a law enforcement officer, or magistrate, no public official who voluntarily swears to support and defend the Constitution and to discharge all duties of their office should be exempt from upholding that oath; therefore, I will veto Senate Bill 2.”

So, according to the governor, oaths are absolute. This, however, doesn’t wash with current law, which requires accommodations for government employees who have religious objections to certain duties. According to the Civil Rights Act of 1964 Title VII, employers are to reasonably accommodate an employee’s or prospective employee’s religious observance or practice if it does not generate undue hardship for the employer’s business.

We Already Accommodate Conscientious Objectors

As Ryan Anderson has also noted, Professor Robin Fretwell Wilson of the University of Illinois Law School, in “Insubstantial Burdens: The Case for Government Employee Exemptions to Same-Sex Marriage Laws,” focuses on the requirement of employers to accommodate religious objectors under the Civil Rights Act and cites a case involving a police officer:

In Rodriguez v. City of Chicago, for example, a Catholic Chicago police officer, Angelo Rodriguez, requested a reassignment after being posted at an abortion clinic in his district. Officer Rodriguez expressed willingness to serve in the event of an emergency breach of peace at the clinic but asked not to be assigned active duty at the clinic since it would violate ‘religious beliefs . . . that prohibit [his] participation in keeping abortion clinics open.’ The Rodriguez court noted that ‘[u]nder Title VII . . . an employer must reasonably accommodate an employee’s religious observance or practice unless it can demonstrate that such accommodation would result in an undue hardship to the employer’s business.’ Indeed, the court ultimately ruled that the city’s offer to transfer Rodriguez to a district ‘comparable to [his own] but without abortion clinics,’ with ‘no reduction in his level of pay or benefits,’178 was ‘a paradigm of reasonable accommodation.’

In the same way, Senate Bill 2 accommodates public officials and puts no undue hardship on the government. While magistrates and clerks are allowed, according to the bill, to recuse themselves, they must do it for all marriages, and any couples (same-sex or heterosexual) will be still be serviced by another magistrate or judge. The bill provides a reasonable balance between the needs of same-sex couples and the religious rights of magistrates and clerks.

Problems with McCrory’s Interpretation

McCrory, however, insisted on vetoing the bill, claiming that a public employee can never be exempted from his duties because he has taken an oath of office. First, performing marriage ceremonies is not technically a “duty” of the magistrate. According to his oath, he is not required to perform marriage ceremonies; he is simply given the authority to do so. Second, if we were to take the absolute nature of the oath to its logical conclusion, does this mean that public officials are required to execute any law—good or bad—in violation of their conscience?

And what about a situation like the current one, involving a new law in which a federal court imposed its will on a state, despite citizens voting to the contrary (North Carolinians voted in favor of Amendment 1, saying that marriage was between a man and a woman)? Magistrates took an oath of office before same-sex marriage was the law. Is it fair for them to lose their jobs because they have a sincere religious objection to something that became law after they had already taken the oath? Yet this is exactly what happened to several magistrates in North Carolina, who were forced to resign or face termination or time in jail.

Finally, McCrory fails to consider that oaths are not absolute; public employees are already given exemptions for both religious and non-religious reasons. Judicial recusal, for example, is a common practice.

Judges Recuse Themselves All the Time

According to Canon 3 of the N.C. Code of Judicial Conduct, judges are disqualified when their “impartiality may be reasonably questioned.” This can happen, for example, when they have a personal bias or prejudice concerning a party, or personal knowledge of disputed evidentiary facts concerning the proceedings; they’ve served as a lawyer relating to the case; the judge has some financial interests; or their spouse is involved in the proceeding.

Of course, a judge is exempted in these circumstances to protect the rights of defendants to get a fair trial—an oath doesn’t stand in the way of those rights. Neither should an oath stand in the way of public officials having their own rights protected. Oaths don’t prohibit conscientious objectors in the military from fighting in wars. When a conflict arises in which a person’s religious beliefs would be compromised, the law, in many circumstances, offers a balance, an accommodation. Why should this situation involving same-sex marriage be any different?

The purpose of Senate Bill 2 is to provide reasonable accommodation to magistrates and clerks who have been confronted with a conflict between their religious beliefs and their jobs. The whole point of the accommodation portion of the Civil Rights Act, as well as other laws on exemptions, is to handle these conflicts. The only other option is to tell an employee that he either violate his conscience or quit his job. Ironically, the Constitution—which McCrory cites as the reason for his veto—protects individuals from just this kind of treatment. That’s true for private employees and those who work in government.

Little Cost to Same-Sex Couples

According to Wilson, accommodations in same-sex marriage cases are being made in the private sector but not the public where employees are paid by taxpayers, heterosexual and homosexual alike. “The states that have embraced meaningful religious liberty protections have exempted religious groups and individuals authorized to preside over marriage ceremonies,” Wilson writes. “But not a single state has shielded the government employee at the front line of same-sex marriage, such as a marriage registrar who, if she has a religious objection to same-sex marriage, will almost certainly face a test of conscience.”

When it comes to religious objections, however, it should not matter who is paying the worker—at issue is religious liberty, both for private and public employees. It seems, however, that many in government think religious objections should be ignored. But, as Wilson says, “this cavalier dismissal of religious objections overlooks the fact that allowing government employees to step aside from facilitating same-sex marriage will cost same-sex couples and the government itself very little.”

This is certainly true in the case of Senate Bill 2, in which same-sex couples will still be able to get married just as heterosexual couples. The bill clearly states, “If, and only if, all magistrates in a jurisdiction have recused under subsection (a) of this section, the chief district court judge shall notify the Administrative Office of the Courts. The Administrative Office of the Courts shall ensure that a magistrate is available in that jurisdiction for performance of marriages for the times required under G.S. 7A-292(b).”

Opponents of the bill who debated on the House floor, however, still rejected protection for religious objections, stating that the magistrates who refused to perform the ceremonies were motivated by hostility toward homosexuals. “But for many people marriage is a religious institution and wedding ceremonies are a religious sacrament,” Wilson wrote. “For them, assisting with marriage ceremonies has a religious significance that commercial services that are subject to non-discrimination bans, like ordering burgers and hailing taxis, simply do not. Many of these people have no objection generally to providing services to lesbians and gays, but they would object to directly facilitating a same-sex marriage.”

McCrory’s decision to veto Senate Bill 2 is based on an absolute view of oath-keeping that the Founders never intended. George Washington said, “I assure you very explicitly, that in my opinion the conscientious scruples of all men should be treated with great delicacy and tenderness: and it is my wish and desire, that the laws may always be extensively accommodated to them, as a due regard for the protection and essential interests of the nation may justify and permit.”

In the case of performing marriages, the magistrates who have been threatened with legal action and forced from their jobs have not been treated with great delicacy and tenderness. When government sets up an oath as absolute, as McCrory has foolishly done, it puts that oath in the place of conscience—such legalism results in bondage, not liberty.