The cover of the first edition of the French satirical weekly Charlie Hebdo to come out after attack on its staff by Islamist radicals has been revealed. Some media are showing the cover and some aren’t. But a few misinterpretations — or at least inadequate interpretations — make the case for why describing the image is no substitute for showing it.

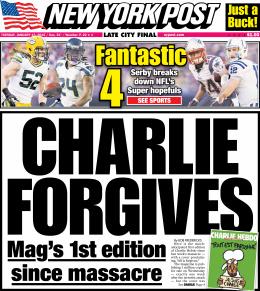

The New York Times’ Rachel Donadio had a great story about the making of the first issue. The New York Times’ Dean Baquet is not publishing images of the cartoon out of cowardice, though he has not been honest about that and instead made contradictory claims dealing with journalism ethics. So no picture was included.

Here’s Donadio’s description:

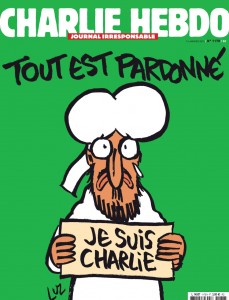

The group was cheering Rénald Luzier, a cartoonist known as Luz, who on the umpteenth try had produced what the editors thought was the perfect cover image for the most anticipated issue ever of this scrappy, iconoclastic weekly, which will appear on Wednesday. It showed the Prophet Muhammad holding a sign saying, “Je suis Charlie” (“I am Charlie”), with the words “All is forgiven” in French above it on a green background.

That was roughly the same as Yahoo’s use of an Agence France Presse article, also not illustrated (though AFP moved the illustration on its wire):

Paris (AFP) – The cover of the first edition of the French satirical weekly Charlie Hebdo since its staff were murderously attacked by Islamist gunmen last week shows a cartoon of the Prophet Mohammed crying and holding up a “Je suis Charlie” sign under the words: “All is forgiven”.

This is technically accurate. The cover depicts someone who is supposed to be Muhammad. He is holding a sign that says “Je suis Charlie.” The words “all is forgiven” are above the image.

And many non-French observers viewed this as a message of forgiveness.

USA Today’s media columnist Rem Reider described the new cover in a video at the newspaper. He said “Sure enough in the tradition of the satirical magazine which has never pulled any punches, there’s the prophet Muhammad but in a way the tone is kind of surprising. It has the prophet saying ‘all is forgiven’ and he’s got a tear coming down. And so it’s not vicious, kind of more in sorrow. With the image of the Prophet, it’s quite a moving statement.”

It would be a very weird and un-Charlie Hebdo image if that were true, though. It would be weird if the simple descriptions of the cover above were true, too. In fact, a subsequent New York Times story by Dan Bilefsky — still not illustrated with an image of the cartoon, given the paper’s unalloyed fear of Islamist extremism — suggests that maybe there’s something more to the image. The piece repeated the anodyne description before admitting “interpretations quickly swirled around the Internet that the cartoon also contained disguised crudity.” Also:

Laurent Léger, an investigative journalist with Charlie Hebdo, shrugged off the idea, circulating on social media, that the cartoon contained one or even two hidden renderings of male genitals. “People can see what they want to see, but a cartoon is a cartoon,” he said. “It is not a photograph.”

They’re slightly hidden to the American eye but not hidden to the French eye. Let’s let Frenchman Pascal-Emmanuel Gobry explain:

First thing French people noticed, all Anglos missed it. So, just fyi: the Charlie cover has a dick on it. pic.twitter.com/FV64AwZ2ys

— PEG ن (@pegobry) January 13, 2015

He went on to explain that jokes about male genitalia and fine wine are basically all that French culture is. Then he mocked, in a really good-hearted way, of course, Americans for their prudery and inability to see this obvious thing.

Now, I happen to think the Charlie Hebdo cover might have more messages in it (or might not). I remember what a surviving Charlie Hebdo cartoonist said about all the newfound friends the news-weekly had discovered in the aftermath of the attacks: “We vomit on all these people who suddenly say they are our friends.” That’s a very Charlie Hebdo message, and was likely directed at those who don’t really believe in free speech or the right to satirize others. Was this cover mocking those of us who claim we’re Charlie Hebdo — holding signs and all! — when we’ll be fair-weather fans? Was it mocking religious concepts of forgiveness, or the failure to practice such forgiveness?

I have no idea. But I do know that people don’t get to experience different reactions to art when that art is censored or hidden. Some of the media outlets that missed the hidden images at least allowed readers to have a chance to catch them. Others simply declared from on high that the image conveyed forgiveness, later declaring from on high that the image might have more to it. Misinterpretations and a limiting of interpretations are both journalistic problems that are easily solved by simply showing the most newsworthy image of the day.

Which only works when you aren’t terrified of Islam and lying about it, as Dean Baquet of the New York Times and other high-level executives are doing.