In a recent post cited by Patheos, nondenominational pastor Brian Zahnd brashly proclaims “You Cannot Be Christian and Support Torture.”

There is no possibility of compromise. The support of torture is off the table for a Christian. I suppose you can be some version of a ‘patriot’ and support the use of torture, but you cannot be any version of Christian and support torture. So choose one: A torture-endorsing patriot or a Jesus-following Christian. But don’t lie to yourself that you can be both. You cannot.

…Any thoughtful person, no matter their religion or non-religion, knows that you cannot support torturing people and still claim to be a follower of the one who commanded his disciples to love their enemies. The only way around this is to invent a false Jesus who supports the use of torture. (The Biblical term for this invented false Jesus is “antichrist.”)

Those who argue for the use of torture do so because they are convinced it is pragmatic for national security. But Christians are not called to be pragmatists or even safe. Christians are called by Jesus to imitate a God who is kind and merciful to the wicked.

Zahnd edited this piece. He states in a “PS” that he originally wrote, “You cannot be a Christian and support torture.” He took out “a” probably because he received a lot of backlash, and rightly so. So he qualified it: “You cannot be Christian and support torture. . . . Can you support torture and go to heaven? Maybe. Can you support torture and be Christlike? No.”

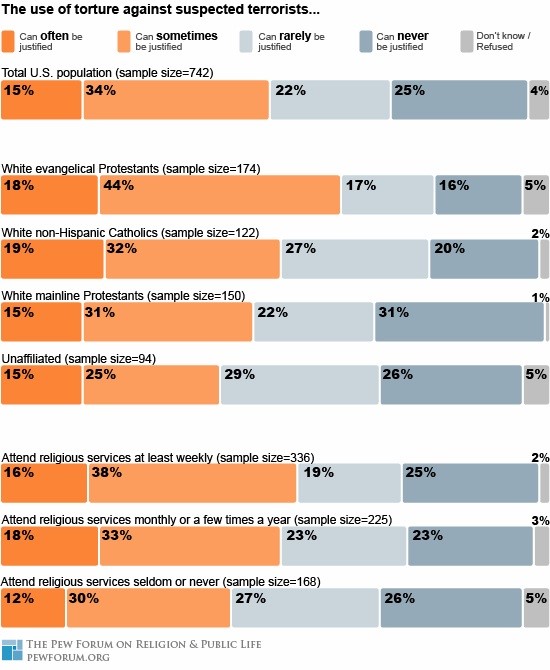

Zahnd can try to disingenuously snake his way out of his own wording, but it’s obvious he’s calling people’s Christianity into question, and that’s what he meant when he initially wrote the post. But even with the qualifier, he is judging 79 percent of evangelicals in America and 78 percent of Catholics (along with 68 percent of all Americans, according to a recent poll)—who say torture can be justified. Yes, not only white evangelicals say torture is justified. White Catholics do, too—a fact overlooked in many articles written about the 2009 Pew survey.

So, can torture ever be morally justified? Or are Christians who support torture simply sellouts to security, as Zahnd says, and possibly doomed to hell?

I think Zahnd and others who make similar judgments are wrong. Torture in some forms and in some circumstances—conducted by the police and military officials—can be morally justified because (1) torture is not necessarily morally worse than killing (i.e., the death penalty); (2) the terrorist has forfeited his right to life and his dignity by his own evil actions; and (3) the innocent lives that can be saved are of higher value than any moral claims by the terrorist who has committed atrocities.

Is Torture Worse Than Death?

Torture is the infliction of severe pain on a defenseless person for the purpose of breaking his or her will. Authoritarian regimes want to break people’s wills to gain or maintain power. Their motives are not to gain important information to save lives, and the torture they conduct is typically prolonged, lasting days, weeks, and even years. This is a maximalist kind of torture imposed on soldiers and even innocent citizens who should not be subjected to such treatment, and it has no place in civilized societies. This is the kind of torture that can be worse than death. It is so devastating, so damaging to both the body and the psyche that the person being tortured loses his self-identity and ability to function as a healthy and completely autonomous human being even after he has been released.

Prolonged torture designed to crush the spirit of an individual is different from interrogation techniques, even ones that inflict pain. Whether these are classified as torture has been hotly debated since the Central Intelligence Agency report on enhanced interrogation techniques was released. However you classify them, the purpose of the techniques is to gain information to save lives, not to exercise power over the powerless.

Interrogative torture is minimal, acute, and designed to gain necessary information to protect society. Some might not feel comfortable using the term torture, but for the sake of this post, I will. It is sometimes morally justified to use pain to break a terrorist’s will in order to save lives. Interrogative torture is not prolonged, maximal, pleasurable, vengeful, or punitive, and it does not have long-term debilitating consequences that completely disrupt a person’s ability to function normally.

This kind of torture is a “lesser evil” than death. While torture does involve the exercise of control over another human being for a time, it does not end their autonomy as death does. When someone is dead, they have no autonomy, no hope of life, and no dignity. They’re dead. However, when a person is tortured in a minimal way, they have not completely lost all autonomy—even in the moment of intense pain. They can still give up information and end the interrogation, or they can remain silent and suffer. There will come a time when the pain will end, when they will regain their autonomy, and they will continue their lives. There is no such hope for a dead person.

It simply does not follow that torturing someone is morally worse than killing them—not in all circumstances. The harm that results from interrogative torture is clearly a lesser moral evil than the harm that comes from killing someone. While a torture victim is physically powerless, they still maintain enough mental faculties to give information and to stop the interrogation. Again, the person who is dead has no such ability. Killing someone takes away his life and autonomy, but torture—while it takes away a person’s autonomy for time—does not take away a life.

Torture Violates Human Dignity?

A primary argument against torture is the same that is leveled against the death penalty—that it violates a terrorist’s human dignity. Some would argue that execution does not violate human dignity, but it would be difficult to argue that capital punishment in the Bible took human dignity into consideration. In the Old Testament, God commanded that people be killed by stoning for various crimes. These included breaking the Sabbath, homosexuality, adultery, and children rebelling against their parents.

If your very own brother, or your son or daughter, or the wife you love, or your closest friend secretly entices you, saying, ‘Let us go and worship other gods’ (gods that neither you nor your ancestors have known, gods of the peoples around you, whether near or far, from one end of the land to the other), do not yield to them or listen to them. Show them no pity. Do not spare them or shield them. You must certainly put them to death. Your hand must be the first in putting them to death, and then the hands of all the people. Stone them to death, because they tried to turn you away from the Lord your God, who brought you out of Egypt, out of the land of slavery. (Deuteronomy 13:6-10)

Stoning was not an immediate death. While sometimes it happened quickly, oftentimes its object would suffer terrible pain, humiliation, and anguish as he bled to death on the street with rocks raining down. The criminal’s dignity was irrelevant. It was irrelevant because he—in the eyes of the law and God—had lost his own sense of dignity. And stoning wasn’t the only method used. The Talmud describes pouring molten lead down the throat of the condemned, beheading, and strangulations—all for crimes such as practicing magic, worshipping idols, or eating something unclean. Throughout Christian history, cruel and unusual punishment as we would define it has been exercised without a thought to the guilty person’s “dignity.”

Yet this is an objection many Christians make in opposing torture. Federalist contributor Rachel Lu makes this point when she says that no matter what a person has done, he maintains his dignity, and other people have no right to violate it.

We should never allow ourselves to forget that enemy combatants are still human beings. Most of them probably aren’t very good human beings, and undoubtedly some are moral monsters. They are not citizens of our nation, nor are they prisoners of war in the proper sense. Still, they are human. This means that they possess that intrinsic dignity and worth that is proper to all human life. Seeing the moral significance of that basic reality is perhaps the most important line that divides a humane and rational society from a terrorist organization or a brutal dictatorship.

The assumption here is that human dignity can never be lost or forfeited. It is part of who we are, and no one has the right to take it away from us. We have the right to life, to our dignity, to our autonomy. In other words, our dignity is absolute in an ontological sense.

While Lu is correct that no human being has the right to take our dignity from us, our dignity is not absolute—it is conditional to our being because we are moral creatures. Unlike our finitude, which is absolute, as well as our physical mortality, our dignity depends on our moral character, our values, our choices, our actions. It exists in relation to God’s law and his righteousness.

Criminals Forfeit Their Dignity

When we make evil choices—especially in the context of murdering people—we forfeit our dignity and autonomy. Our own choices have diminished our dignity, and it cannot be called up to save us from receiving the punishment we deserve—or the consequences that come with our own actions. This is why it is just to take away a criminal’s freedom when he commits a heinous crime. Criminals have forfeited their right to be free, and they have abandoned their own sense of worth and value by taking another’s life. They have made that choice. They have done that to themselves.

Thomas Aquinas makes this point quite clearly in his defense of killing criminals:

By sinning man departs from the order of reason, and consequently falls away from the dignity of his manhood, in so far as he is naturally free, and exists for himself, and he falls into the slavish state of the beasts, by being disposed of according as he is useful to others. This is expressed in Ps. 48:21: ‘Man, when he was in honor, did not understand; he hath been compared to senseless beasts, and made like to them,’ and Prov. 11:29: ‘The fool shall serve the wise.’ Hence, although it be evil in itself to kill a man so long as he preserve his dignity, yet it may be good to kill a man who has sinned, even as it is to kill a beast. For a bad man is worse than a beast, and is more harmful, as the Philosopher states (Polit. i, 1 and Ethic. vii, 6).

“A bad man is worse than a beast, and is more harmful.” Aquinas’ words are definitely in line with how God treats criminals in Scripture. Human dignity is not seen as an absolute, but as conditional. This makes it morally justifiable to kill people who have violated the law—man’s law and God’s law. Since interrogative torture is not worse than killing, and killing is morally justified because human dignity has already been lost, interrogative torture is morally justifiable.

If killing were not morally justifiable on the basis of human dignity, God would be a monster. But he isn’t. Why? Because of human guilt. Even though the Bible says, “Thou Shalt Not Kill,” God orders Joshua to “go in and clean house, and don’t leave anything breathing! Don’t leave a donkey, child, woman, old man or old woman breathing. Wipe out Jericho!” He can order this because those people had violated God’s law and in so doing had forfeited their rights and lost all sense of dignity. Even as we struggle with the fairness of this from our limited human perspective, the fact that this occurs in Scripture cannot be denied. The justification for it lies in the guilt of the people being punished. If killing were not morally justifiable—and if human dignity were intrinsic to our being no matter what we do—then hell itself would be a profound injustice because people would be tortured for eternity with their dignity intact. How can this be reconciled with the absolutist view of human dignity?

If it is morally justifiable to stone a criminal to death, which is punitive (or even kill someone out of self-defense or to save a life that is threatened), would it not follow that it would be morally justified to torture a criminal to get information out of him in order to save a life? If we choose not to torture someone so we can save a life, then we are placing the dignity of the criminal over the life and dignity of the innocent person who is about to die—something the Bible doesn’t do. The Bible does not recognize the autonomy and dignity of the evildoer. God didn’t, for the foreign nations who were not covered by his covenant. The theocracy of Israel didn’t, which is why people were stoned to death for adultery and other crimes. And it is why, now in the new dispensation, the government (though not the church) is to wield the sword and “violate” the autonomy of the guilty, and we’re to recognize the state’s authority when it does:

Let everyone be subject to the governing authorities, for there is no authority except that which God has established. The authorities that exist have been established by God. Consequently, whoever rebels against the authority is rebelling against what God has instituted, and those who do so will bring judgment on themselves. For rulers hold no terror for those who do right, but for those who do wrong. Do you want to be free from fear of the one in authority? Then do what is right and you will be commended. For the one in authority is God’s servant for your good. But if you do wrong, be afraid, for rulers do not bear the sword for no reason. They are God’s servants, agents of wrath to bring punishment on the wrongdoer. Therefore, it is necessary to submit to the authorities, not only because of possible punishment but also as a matter of conscience. (Romans 13, emphasis added)

Government Rightly Uses Force to Protect Society

While the new dispensation fulfills the old in the Church, it does not make these old laws invalid. In Matthew 5:18, Jesus says: “For truly I tell you, until heaven and earth disappear, not the smallest letter, not the least stroke of a pen, will by any means disappear from the Law until everything is accomplished.” Christians are no longer under the Mosaic Law, but this does not mean there are no longer temporal punishments delivered by the government—a government that God means will use force to protect society, not to be a charitable institution. The Bible makes it clear that those who live by the sword will die by the sword. If you kill, you forfeit your right to life. You have become, as Aquinas said, worse than a beast.

This doesn’t mean the government can do anything it likes to criminals just because they’re guilty. It is not our right to exercise power for the sake of power. If we are forced to use interrogative torture, we do it to save lives, not to abuse the criminal for the sake of empowerment or even punishment. And this action is to be done, not by individuals, but by the government, which has been given the authority of the sword by God himself.

People like Zahnd who speak of God’s forgiveness and mercy and the many commandments in Scripture for God’s people to turn the other cheek and love their enemies make the mistake of applying these commandments meant for individuals also to the government. While it is a Christian’s duty to love and forgive, it is the state’s duty to punish criminals—even to put them to death.

The good news is that there is hope even for the evildoer. If there is repentance, there is forgiveness, there is restoration of dignity. This is the hope of the Gospel and the promise of Christ who died for our sins. If you put your faith in him, he is faithful and just to forgive and cleanse you of all unrighteounsess. But for those who commit evil, who live by the sword, they will surely die by it. And those who refuse to show mercy will suffer at the master’s hand: As Jesus said of the unmerciful servant in Matthew 18, “In anger his master handed him over to the jailers to be tortured, until he should pay back all he owed. ‘This is how my heavenly Father will treat each of you unless you forgive your brother or sister from your heart.’”

Guilt and Innocence Matter

While forgiveness and mercy are a matter for individuals, it is the role of the government to protect and punish. When it comes to protection, innocent lives that can be saved are of higher value than any moral claims by the terrorist who has and will commit atrocities. Guilt and innocence matters. If government officials have a known terrorist in custody, and it is certain that he has information needed to save lives, it is morally justified for them to use interrogative torture to get the information necessary to protect innocent life.

Once again, I turn to Aquinas. In defense of the death penalty, he wrote that the reason it is necessary to kill a criminal is not simply to punish him, but to protect society “to safeguard the common good.” When the good are “protected and saved by the slaying of the wicked, then the latter may be lawfully put to death.”

If, according to Aquinas, the good can be saved through killing the wicked, then it would seem to follow that the good can be saved through interrogative torture, which is a lesser evil than killing. If we’re willing to kill in war to protect our homeland, why are we not willing to inflict temporary pain on a terrorist to save lives? The people who are killed on the battlefield will never walk again, they will never feel the sun on their faces, or eat a hot meal, or touch another human being. The terrorist who has been tortured will—and those he has threatened will, too.

The Catechism of the Council of Trent expounds on this theme when it says that lawful slaying to “protect the innocent” is just use of civil power. “The just use of this power, far from involving the crime of murder, is an act of paramount obedience to this Commandment which prohibits murder [Thou shalt not kill]. The end of the Commandment is the preservation and security of human life. Now the punishments inflicted by the civil authority, which is the legitimate avenger of crime, naturally tend to this end, since they give security to life by repressing outrage and violence. Hence these words of David: In the morning I put to death all the wicked of the land, that I might cut off all the workers of iniquity from the city of the Lord.”

John Yoo, who was instrumental in setting up the Guantanamo Bay detention center, said in an interview in 2007 that there are situations when torture is justified:

Death is worse than torture, but everyone except pacifists thinks there are circumstances in which war is justified. War means killing people. If we are entitled to kill people, we must be entitled to injure them. I don’t see how it can be reasonable to have an absolute prohibition on torture when you don’t have an absolute prohibition on killing. Reasonable people will disagree about when torture is justified. But that, in some circumstances, it is justified seems to me to be just moral common sense. How could it be better that 10,000 or 50,000 or a million people die than that one person be injured?

Peter Levine, a professor at Tufts University, says that Yoo asks a serious question, and while he tries to respond it, he’s not satisfied with any of his answers.

We have a good reason to safeguard the rights of captives: our own government can take us prisoner. If we lose habeas corpus for suspected terrorists, we can lose it for ourselves. That is certainly a concern, but it doesn’t excuse acts of war on foreign lands that may cause individuals to suffer worse than they would under torture. A pacifist replies: War is never acceptable. But what about in 1940? Or 1861? Or 1776? If war is ever justified, then we will sometimes kill people. And if killing is worse than torturing, why should we ban the latter–especially if it proves an efficient means of preventing casualties?

Levine, like most of us, doesn’t feel comfortable with torture, but the argument that it can be effective in saving lives is compelling. Some call this pure utilitarianism, but if you can kill to protect society, and some forms of torture are not as bad as killing, then does it not follow that it is morally justified to use torture to save lives?

One of the problems we have in this debate is the tendency to make no distinction between the guilty and the innocent. Someone says he would never advocate torture to save the innocent. But is that realistic or even honest? What if a bomb is about to go off in your child’s school? The authorities have captured a terrorist who has information on where the bomb is. They know he has this information, and they’re running out of time. Would you allow your child to die in order to save the dignity of a terrorist? Some say they would, but is the value of a criminal’s dignity—dignity he doesn’t value himself as he’s abandoned it—more valuable than your child’s life?

Will the Torturer Lose His Soul?

The issue here is not over using power for power’s sake, which is often the case with torture. It is acting for a higher moral purpose. Dietrich Bonhoeffer certainly understood this dilemma when he participated in a plot to assassinate Hitler. You can read the heaviness of his choices in the following passage:

We have been silent witnesses of evil deeds. We have become cunning and learned the arts of obfuscation and equivocal speech. Experience has rendered us suspicious of human beings, and often we have failed to speak to them a true and open word. Unbearable conflicts have worn us down or even made us cynical. Are we still of any use? We will not need geniuses, cynics, people who have contempt for others, or cunning tacticians, but simple, uncomplicated, and honest human beings. Will our inner strength to resist what has been forced on us have remained strong enough, and our honesty with ourselves blunt enough, to find our way back to simplicity and honesty?

Choosing between two evils is never easy, but it is a situation created, not by those trying to find resolution, but by the criminal who has chosen evil over good. Some argue that torture necessarily dehumanizes the one carrying it out. This is an interesting admission, especially when these same people say that a criminal doesn’t dehumanize himself by his own evil deeds—that he doesn’t forfeit his dignity. How can a torturer dehumanize himself by inflicting pain if a murderer doesn’t dehumanize himself by killing others? It seems that our immoral actions do affect us, do diminish us, do reduce us, as Aquinas said, to a level lower than beasts—both for the torturer and the murderer.

Leaders in law enforcement have been known to say that they would never want someone on their force who can carry out torture and not be affected by it—precisely because it does have a dehumanizing effect. These concerns are valid. Indeed, if someone were to torture and not be affected by it, he would be a sociopath and dangerous in society. No one is saying employing torture techniques will leave a person unaffected. Bonheoffer was certainly affected by his role in the conspiracy to kill Hitler, but does this mean he was necessarily dehumanized? Not when the motive and the purpose is a higher good—to defend the defenseless, to save lives.

Most everyone would say that if they randomly killed someone, they would be psychologically and spiritually harmed. But if they killed someone who was trying to rape or kill their daughter, they would find peace with it because they will have known it was necessary to protect the one they loved. Context and motive make all the difference. They would be affected, of course. There would be no delight, no pride, no joy. There would be grief and pain, but there would be a measure of calm and acceptance that what had to be done was done to save a life—to defend the defenseless and protect the good. This is why it is important that when we consider these kinds of measures—measures that have been forced upon us as we live in a barbaric world where the wicked terrorize the innocent—that we remain true to our purpose and only resort to these extremes when there is no other choice.

What About Due Process?

How do we work through these difficult issues legally? Do we want our government to have the power to interrogate people it considers guilty without accountability and due process? First of all, a terrorist is not an American citizen and does not have the rights of due process given to American citizens (or they shouldn’t). The Geneva Convention says prisoners of war are “Members of other militias and members of other volunteer corps, including those of organized resistance movements, belonging to a Party to the conflict and operating in or outside their own territory, even if this territory is occupied, provided that such militias or volunteer corps, including such organized resistance movements, fulfill the following conditions: (a) that of being commanded by a person responsible for his subordinates; (b) that of having a fixed distinctive sign recognizable at a distance; (c) that of carrying arms openly; (d) that of conducting their operations in accordance with the laws and customs of war.”

Terrorists don’t meet b, c, and d. They do not wear uniforms. They hide among civilians and innocents. Their arms are usually concealed. They don’t conform to the laws and customs of war but target innocent people.

Second, it would be unwise to have torture legalized and institutionalized because such license would be dangerous left unchecked in the hands of the powerful state. Alan Dershowitz, a Harvard University law professor, offers a reasonable solution.

I think every president would at least consider the option of torture if confronted with an actual ticking bomb. President Clinton said he would consider torture and President George W. Bush actually authorized the use of waterboarding, even in non-ticking bomb situations. Bush denied that waterboarding and other forms of extreme interrogation measures he approved were torture, but they would seem to fit any reasonable definition of that term.

If I’m right, and if every president would, in fact, consider opting for the torture of one terrorist rather than permitting thousands of innocent Americans to be blown up, then the following question must be asked: Would it be better or worse for a law to be passed requiring the president to secure a warrant before (or, in a real emergency, during or right after) he could employ this drastic measure? Such a law would implicitly legitimate torture in extreme situations, and that’s a bad thing, but it would also create visibility and accountability, which is a good thing.

A danger of torture warrants is that there would be no check on how often they are given, and the result would be that torture would become more normal. That’s certainly a risk. The only other option is to keep all forms of torture and enhanced interrogation illegal and let those who find themselves faced with the ticking time bomb scenario or something similar fall on the mercy of society and the courts. If this is, indeed, the only solution, I hope the courts and the public will show leniency, since torture is morally justified in extreme circumstances and those men and women who are caught between two evils but who humbly act according to conscience—even when it is contrary to the law—will be shown the respect and gratitude they deserve.