According to conventional wisdom, Americans start paying closer attention to elections after Labor Day. The reality they will return to after their summer vacation from American politics is highlighted by popular unrest (centered, for now, in Ferguson, MO) and elite partisanship (featuring an indictment in Austin, TX, and lawsuits and impeachment talk in Washington, DC). In other words, they’ll return to a political setting much the same (with different flash points) as the one they left behind in late May.

These headlines and the apparently perpetual problems they highlight represent an unpleasant distraction from the already overwhelming busyness of daily life, and thus promise to keep a good portion of the American public on the political sidelines, and an even larger group of Americans questioning the direction of the country. A stale inertia seems to be the norm, a political game without a clear-cut winner and many a participant injured along the way.

Upon closer examination, however, one finds, as we argued last week, that the reverse is true: that there is a dynamic force in American politics producing a consistent winner capable of putting the dynasties of the Yankees, Celtics, Canadiens, and Steelers to shame: Progressivism and its champion, the DC Oligarchs, whose worst season still rewards handsomely its dedicated if dependent fan base.

How is it that in a hyper-egalitarian age a purportedly democratic ideology has produced the seemingly-intractable oligarchic ruling class that dominates American politics?

Alexis de Tocqueville provides a clue in Democracy in America: “Democratic nations often hate those in whose hands the central power is vested, but they always love that power itself.” Whereas democratic equality promised to make men free and independent, Tocqueville argues that it eventually empowers collective institutions rather than individuals, as democratic peoples love “public tranquility”–and no power promises to secure a more stable peace than the centralized state.

Political victory in a democratic age requires partisans to present a vision of peace acceptable to the multitude and to demonstrate thereafter that they are best prepared to keep the peace. Progressive oligarchs have been wildly successful on both fronts, promising a peace like no other–prosperous and perpetual–and employing the accumulated resources of the United States to carry out their program, all the while winning many of the rhetorical battles with pleasing slogans that appeal to the vanity, prejudices, and passions of the people. While following a banner promising more liberty and freedom, individuals find themselves more powerless against the vicissitudes of life, and more willing to exchange their liberty for security.

The American founders were very much aware of this paradox of democratic politics, as James Madison demonstrates in Federalist 58. Although sympathetic to those wishing to see the House of Representatives grow with the American population, Madison warns that the larger the assembly, “the greater the ascendancy of passion over reason”–and the “the fewer will be the men who will in fact direct their proceedings.” He continues:

The countenance of the government may become more democratic, but the soul that animates it will be more oligarchic. The machine will be enlarged, but the fewer, and often the more secret, will be the springs by which its motions are directed.

Perhaps no two sentences could better summarize the political consequences of Progressivism as they have unfolded over the last century. Popular election of senators, universal voting rights for women, state-level tools like initiative and referendum: all were democratizing measures advocated and enacted with energy by Progressives in the first two decades of the 20th century. And yet, a century later, the individual citizen has a smaller share in his own governance, less confidence in less accountable leaders, and less control over his daily life than at any previous point in our nation’s history–and every instinct of the ruling class promises to make things even worse.

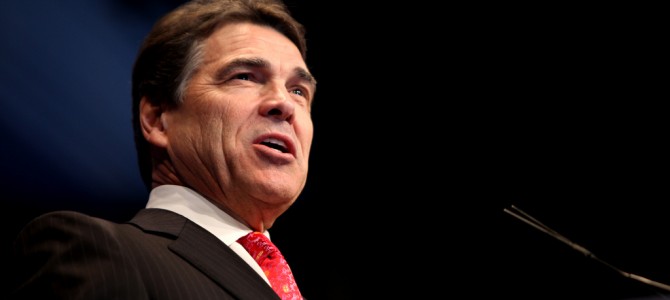

Consider an important parallel between the lawsuit against President Obama and the recent indictment of Texas Governor Rick Perry.

A month ago, President Obama was all but begging House Republicans to impeach him, cynically calculating, it would seem, that nothing would raise money for the fall election campaign or energize otherwise dispirited Democratic voters like a good impeachment. Speaker Boehner, of course, demurred, fearing perhaps that President Obama’s calculations might be correct, and instead hoping a stern lawsuit might keep more spirited Republican voters energized. However this plays into the midterm election campaign, one result is assured: that a political dispute over executive power has been turned over to the non-political branch of government for proper expert disposal.

Ditto the ongoing struggle between Austin and the rest of the state of Texas, which resulted in Governor Perry’s indictment on extremely flimsy abuse of power charges. “If you can’t beat them, indict them” is an ugly mode of politics, but it is also the negation of politics–another deferral to the experts, of sorts.

Democratic passions beget a trump-card style politics and oligarchic management. Is there any feasible alternative?

James Madison did not expect that the American republic, if properly constructed, would inaugurate an era when reason reigned unchallenged. In fact, given human nature, he didn’t even advocate that. “[T]he most rational government will not find it a superfluous advantage to have the prejudices of the community on its side,” he argued in Federalist 49. What he cautioned against, rather, was liberating passion from any responsibility to right.

In Federalist 49, that meant cultivating a “veneration” for the good government created by the Constitution; buttressing the conclusions of “enlightened reason” with the “prejudices of the community.” In Federalist 58, he showed how calculations of personal honor and interest–and the House’s control over government spending–could be used to move the reluctant to support “every just and salutary measure.” Republican politics, as Madison described (and practiced) it, is fundamentally about persuasion toward the good–not the coercive passion of the mob or the coercive decree of the functionary.

Madison knew very well what Aristotle had taught 2000 years before–that persuasion is an art involving the reason and the passions of the audience, as well as the character of the speaker. Republican government respects the dignity of the individual not only by protecting his fundamental rights, but by addressing him as a whole, mature human being, not as an animal to be controlled or a child to be commanded–and not as a hyper-rational Vulcan, either.

In different ways, this is equally absent from the Boehner lawsuit, the Perry indictment, and more or less any speech by President Obama. Speaker Boehner could make the public case against the president’s lawlessness in pressing for impeachment or by invoking Madison’s favorite tool, the power of the purse–perhaps persuasively, given the merits of the case. Governor Perry’s opponents could make their own argument about executive abuse if they dare or look for a more plausible line of complaint. President Obama could engage real opponents rather than strawmen and real arguments rather than caricatures. All would then be forced to lead in a truly republican manner, grappling publicly with justice in a more responsible and meaningful way in order to win the assent of the people at large.

But they haven’t and therefore they didn’t. The question that remains is whether that will matter. Those checking in after a summer away from politics can as easily check out again. The minority planning to vote in November can vote their bum back in and hope everyone else throws theirs out. The wheel will turn; the breathless analysis will be written; Washington will yawn, as the Oligarchs win again.

Or the silent, discontent, and disengaged majority will awaken to the reality that the peace they’ve been promised is a political mirage, and that only through their active life-long engagement is regime change possible in the United States. A republic, if you can keep it; a republic if you can reclaim it.

David Corbin is a Professor of Politics and Matthew Parks an Assistant Professor of Politics at The King’s College, New York City. They are co-authors of “Keeping Our Republic: Principles for a Political Reformation” (2011). You can follow their work on Twitter or Facebook.