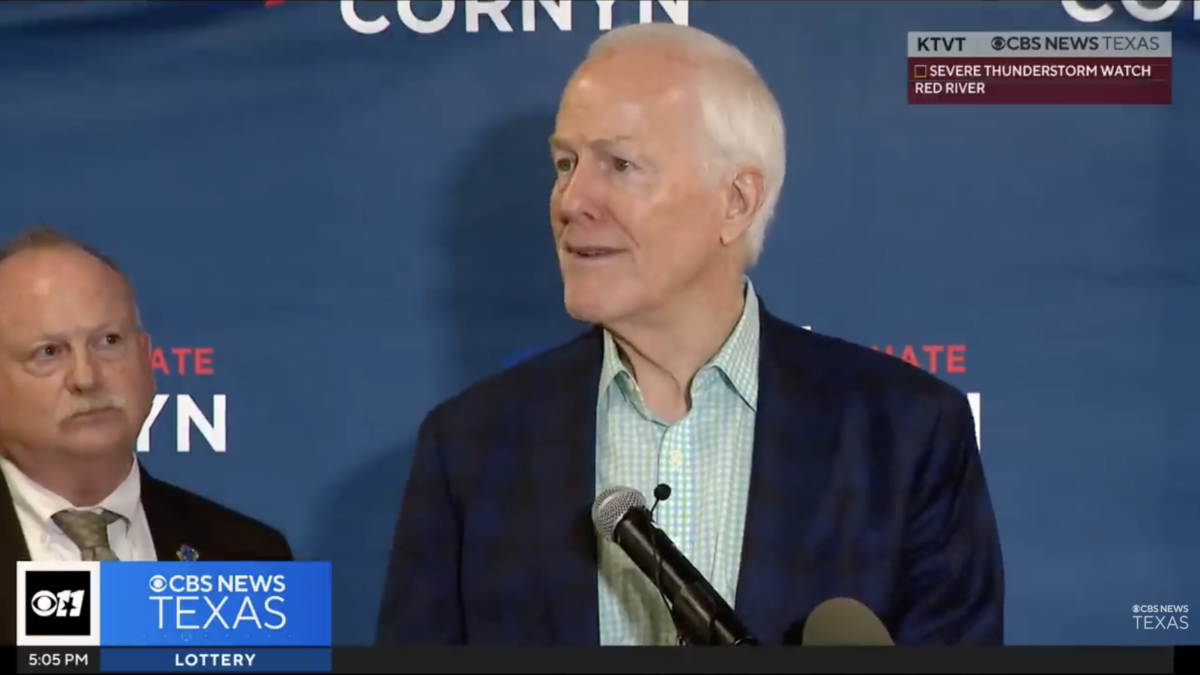

Tim Kreider called for visionary — and anti-capitalist — science fiction in a recent article in New Yorker. Tyler Cowen replied that we may be safer if plans to remake society, sometimes in violent fashion, remain the stuff of fiction, and he wonders if any sci-fi captures that point.

I suspect Kreider would reply that he’s not calling for the immediate remaking of society so much as a tentative effort to understand it in all its complexity — but any social conservative who has watched deconstructionists ignore the lessons of tradition, and any free-marketeer who has heard intellectuals’ warmed-over Marxist attempts to understand economics, can tell you where overconfident explanations of society often lead.

It may be telling that Kreider wrote a book of essays and cartoons called We Learn Nothing, about the ways individuals repeat their mistakes in love and other pursuits — and telling that he laments current literature’s focus on “issues with our parents, relationships, and death.” Whereas a conservative writer might warn that humans are just as likely, if not more likely, to bungle things when applying past experience to new plans for society as when trying to fix their own private lives — and an optimistic libertarian writer might note that people are far more rational in planning their own lives than in planning others’ — left-liberals have a tendency to think that humans’ ability to plan collectively is inversely proportional to their ability to plan their lives as individuals.

A more concrete example: the most neurotic of my fellow New Yorkers tend also to be the people most likely to think sense and order can be imposed on our messed-up lives from above. Politics becomes a route to redemption. Or as one comic book industry professional who is a self-proclaimed communist put it when I first met her here seventeen years ago, “Capitalism is a terrible system — it allowed me to get $60,000 in debt.” The left-liberal imagining being saved from herself is analogous to those social conservatives who look at their own bad habits and conclude that the whole world badly needs religion.

Similarly, think how much of science fiction, even when not consciously dissecting capitalism, is shot through with the longing for a more-rational human (or humanoid) race, accompanied by harmonious but deceptively simple models for a society worthy of such beings. You see it not just in, say, the stripped-bare, math-word-problem-like astronaut and scientist characters in Isaac Asimov short stories but in every mid-century tale featuring serene, high-minded elders in flowing robes lording it over domed, modernist, usually somewhat bland cities. Soothing visions for us uptight nerds.

The most dangerous thing about intellectuals, though, is that they imagine the real world is as simple as their theories. Much as I love sci-fi, it presents great temptations to simplify, even in works as richly textured as Kim Stanely Robinson’s ecologically-minded Mars books (praised by Kreider) or Frank Herbert’s Dune books (noted by Cowen). Far be it from me to tell artists to be less ambitious, but there is always a danger — even when they’re just writing about those failed romances or for that matter bank heists — that they’ll start to mistake their tiny models for reality. Then, by depicting those models with passion, they’ll make us feel almost as if the models are real or should be made so.

Plato was no dope, then, when he suggested that the ideal republic would have no poets. He knew how easily art leads us astray. Would that he had realized that rationalistic philosophical models — of an ideal republic, for instance — can also mislead. Far from “capitalism’s victory over our hearts and minds” being complete, as Kreider laments in his essay, our entire culture, nay our very instincts, have long been prey to the socialist temptation. It’s there every time we imagine, much like arrogant planners or philosopher kings, that we’ve “got a handle on the whole social situation” — whether we call that presumption sci-fi, avant-garde theatre, macroeconomic aggregates, dialectics, or Utopia.

Even science itself — not the hard facts, but the rhetorical way in which they are presented — often falls prey to the temptation, never mind science fiction. I am reminded that what was declared #6 among “The 15 Best Behavioral Science Graphs of 2010-2013” was a graph showing that people interacting with each other can be more callous than a lone individual making an ethical decision. Since the interactions studied were trades, the authors reached (and touted) the conclusion that markets impair morals — yet they might at least have investigated whether participating in other interactions, such as voting or for that matter obeying a king or Fuhrer, produced as much or even more callousness than market interactions.

Failure to do so is a perfect example of how science presents factually-accurate, even detailed, yet dangerously misleading information amidst a pretense of providing more context. I tried suggesting this in a comment on another scientist’s Facebook post about the year’s best graphs, only to have the comment deleted with a warning that fascism should not be mentioned unexpectedly — not even, apparently, in a disapproving way and as a highly-relevant topic of further study.

Since Kreider appreciates the science of ecology (central to Kim Stanley Robinson’s books), he might think of the problem of overly-simple models as comparable to the dangers of creating a terrarium and expecting it to replicate all the nuances of an entire rain forest. Such an experiment might well be worth a try but probably only if done with its drastic limitations in mind — perhaps even with the primary purpose of illustrating those shortcomings. Frank Herbert, J.R.R. Tolkien, and Kim Stanley Robinson just barely begin to gesture feebly at the rich complexity of real societies – which have subtle, often unnoticed, subsidiary systems — and all three writers notoriously had to put a hell of a lot of work into it even to get that far.

Most writers, understandably, are still struggling to capture accurately what something as simple as, say, an awkward Christmas dinner feels like. They struggle even when drawing heavily from their own family experiences. We probably ought to admire the humility of their ambitions.

Coincidentally and tragically, as I write this, word reaches me that Ned Vizzini, one of my fellow New York Press veterans and the young author of the sci-fi novel Be More Chill, about the difficulty of fitting in in high school, has committed suicide, despite much of his short writing career having been devoted to trying to understand depression. His very life depended on figuring out one phenomenon with which he had direct experience, and he still couldn’t quite master it. Should the rest of us pretend to have figured out civilization?

I am not suggesting writers avoid addressing politics. In fact, I’m helping to launch a new libertarian site for writers and artists called Liberty Island and will have a short story up on the site about history itself being altered. I just wish all artists would understand what complex matters they’re delving into when they address politics. Consider the possibility that an advanced capitalist economy is as complex and as deserving of respect as the mind of the angst-ridden teen in your short story, at the very least.

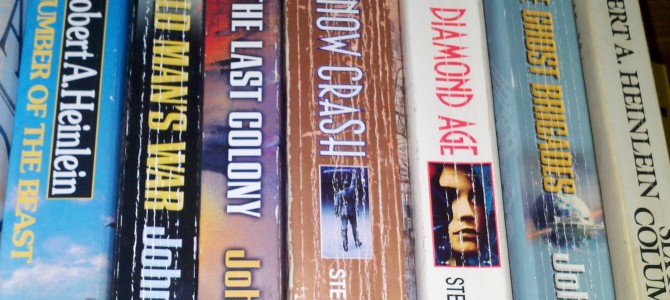

Given the omnipresent temptation to create socialist art, we probably ought to be very grateful for those rare works that address politics and capture some of the complexity of markets. The sci-fi novel Snow Crash by Neal Stephenson is perhaps the most engaging (and sometimes disturbing) depiction of a fully-privatized, governmentless, anarcho-capitalist society (like the one I hope to live in one day). The dystopian libertarian novel Alongside Night by J. Neil Schulman is now being made into a low-budget film. There’s been a healthy trend on television dramas in recent years toward depicting politics as messy and imperfect, even if markets are rarely offered as an alternative, and the best moments of Babylon 5, Star Trek: Deep Space Nine, and Battlestar Galactica captured the intractable problems of factionalism and personality cults.

George Saunders, who Kreider calls “the only major American author I can think of off the top of my head who’s grappling nakedly with the disfiguring effect of capitalism on the human soul,” says he used to be an Objectivist, that is, an adherent of what Kreider calls “Ayn Rand’s…brand of enlightened assholism.” I’m not an Objectivist myself (I am disqualified due to my appreciation for utilitarianism, altruism, and ambiguity), but Rand, ironically, may be the author striving most mightily of all those Kreider mentions to depict economics and social context.

Surely, despite all the dismissive jokes made about the (at times sci-fi-like) Atlas Shrugged, it is one of the only major literary attempts to depict the society-wide side effects of economic regulation, crony capitalism, and intellectual dishonesty. Its scope is so broad and its characters so numerous, you might well call it dialectical — or at least see it as a “Russian novel.” Kreider should be delighted with her, right? No? And Rand’s topics are surely timely, given that a recent poll shows 72 percent of the population thinks big government is one of the greatest threats we face. But perhaps, critics might argue, Rand failed to separate herself sufficiently from the Cold War context (and mindset) in which she wrote.

Here’s a challenge, then, for sci-fi writers who dare to think big and reimagine society, if that’s what Kreider says he wants: Imagine the world as it might be if humanity had never made the collectivist error in the first place. Imagine history as it might have been if, say, Plato had advocated strict property rights and individualism instead of wanting communal living and “guardians” who oversee the rest of us. I think we might by now be immortal and living among the stars.

All right, Tim Kreider, fair enough. Maybe there is room for more visionary sci-fi.

Follow Todd Seavey on Twitter.