Colorado usurped federal court authority in dumping former President Donald Trump from the Republican presidential primary ballot, according to an amicus brief submitted to the U.S. Supreme Court.

The brief, filed by attorneys for election integrity organizations in Michigan and Wisconsin, argues that the U.S. Constitution and federal law limit states’ authority to disqualify a candidate, powers expressly given to the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia — and only after an election.

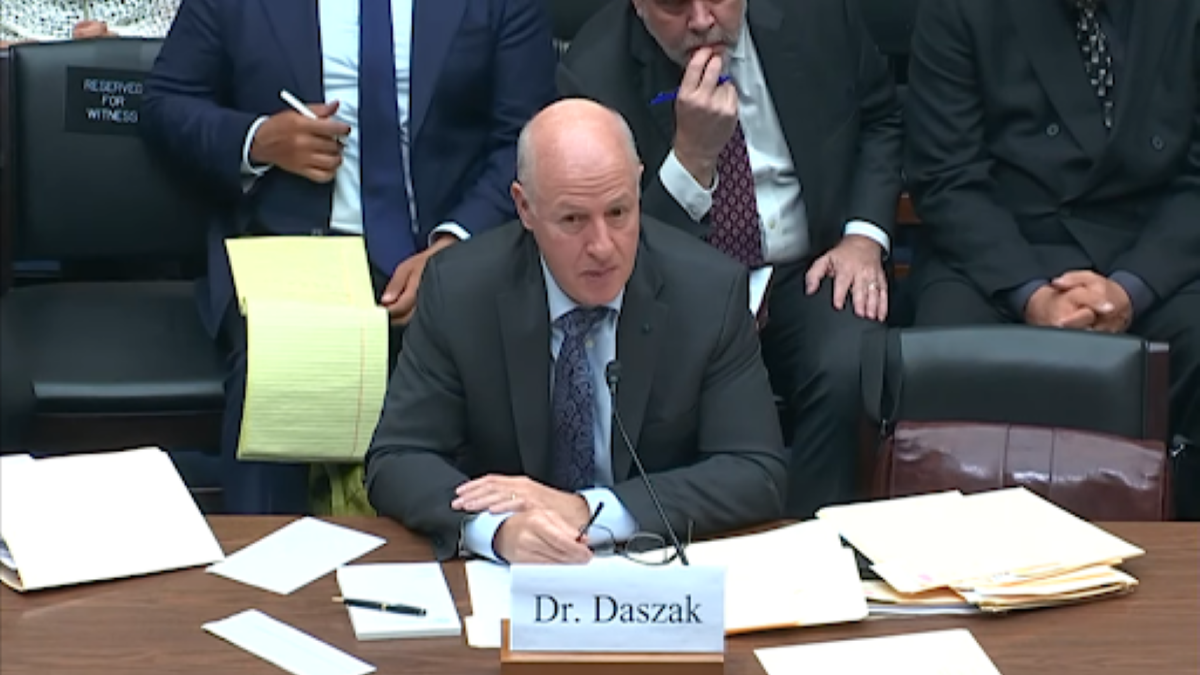

Erick Kaardal, representing the Wisconsin Voter Alliance, Pure Integrity Michigan Elections, and Michigan Fair Elections, says Trump-aligned attorneys have failed to raise the issue in their appeals before the Supreme Court, which is scheduled to hear oral arguments Thursday on the Colorado Supreme Court’s suspect ruling. He says the left has already signaled its interest in challenging Trump’s eligibility in the D.C. court, should Trump be elected in November, but he insists the Supreme Court would be loathe to upend the will of the people and turn out a president-elect.

A Question of Jurisdiction

While Trump’s attorneys and others in support of the former president rightly argue the Colorado court made “a slew of legal errors,” the brief filed by the election integrity groups argues there is also a jurisdictional problem. The Colorado Supreme Court’s decision allowing Trump to be tossed from the state’s ballot violates the U.S. Constitution’s Electors Clause, according to the brief.

“In summary, under the Electors Clause, a state running a statewide presidential election, primary or general election, is preempted from excluding any Article II, section 1, clause 5 qualified presidential candidate from any presidential ballot because the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia has exclusive quo warranto jurisdiction after the President-Elect is elected to determine disqualification,” the court filing states.

The argument is that states may remove a presidential candidate from the ballot for failing to meet the Article II, section 1 requirements on age, citizenship, and residency. States may also disqualify a candidate who fails to meet nominating requirements. Those exceptions do not apply in Trump’s case.

All other disqualification authority, the brief argues, rests on the shoulders of the D.C. Court.

“Congress enacted D.C. Code § 16–3501 showing a clear and manifest purpose that the disqualification of Presidents was to be done in the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia, not in the states prior to the election of the President-Elect,” the court filing states.

Quo Warranto

Congress did so with the idea of quo warranto, a writ or legal action “used to challenge a person’s right to hold a public or corporate office.” In the case of D.C. Code § 16–3501, quo warranto is applicable to officeholders in the District of Columbia, like the president of the United States. Kaardal argues that the law gives the D.C. court the authority to determine whether the president-elect or, should the individual have taken the oath of office, the president is qualified to serve.

The brief cites a 1915 U.S. Supreme Court case involving a newspaper reporter nominated by President Woodrow Wilson and confirmed by the Senate to serve as civil commissioner of the District of Columbia. The Supreme Court ultimately found that the resident who brought the case against the commissioner did not have standing, but noted that quo warranto may be used in disqualification of federal officers.

“This fact also shows that 1538-1540 of the District Code, in proper cases, instituted by proper officers or persons, may be enforceable against national officers of the United States. The sections are therefore to be treated as general laws of the United States, not as mere local laws of the District,” the opinion, written by Justice Joseph Lamar, states.

So, the election integrity groups argue, “disqualifying a President-Elect, even a future President-Elect, i.e., a presidential candidate, is a federal power that could only be exercised by the federal government after the presidential candidate is elected as President-Elect.”

The left-leaning Project on Government Oversight (POGO) telegraphed the left’s potential use of quo warranto to get Trump in its 2022 recommendations to the highly partisan congressional Jan. 6 committee.

“The writ of quo warranto generally allows a court to hear challenges to a person’s right to hold public office and remove an unqualified individual from office. In many jurisdictions, quo warranto rules are now codified. At the federal level, Congress codified quo warranto in the District of Columbia Code,” the report notes. “Under the quo warranto law, the federal district court in Washington may issue a writ of quo warranto against anyone in the District who unlawfully holds ‘a public office of the United States.'”

Binkley and the Ballot Battle

The filing is one of 78 amicus — or friend of the court — briefs filed in Trump v. Anderson, in which Trump has appealed the decision of the Colorado Supreme Court to disqualify him from the ballot under the dubious claim that the former president violated the “insurrection clause” of the 14th Amendment. The brief is one of 14 filed in support of neither party.

In fact, the filing grew out of little-known Republican presidential candidate Ryan Binkley’s legal fight for ballot placement in Minnesota. Binkley, also represented by Kaardal, was found not to have met the requirements laid out by the Republican Party of Minnesota to appear on the state’s 2024 primary ballot. The party demanded qualifying candidates had to have appeared at the first GOP presidential primary debate in Milwaukee last August or have held high-ranking office, such as president, vice president, member of Congress, governor, or mayor of a city with more than 250,000 residents.

While Binkley meets all the basic constitutional qualifications, the Texas pastor with little national name recognition could not qualify under the party requirements. The Minnesota secretary of state barred Binkley from the primary ballot, and the Minnesota Supreme Court upheld the decision, shooting down the argument that the state had no authority to disqualify the candidate on such grounds. They found the petitioners’ claim lacked legal merit, but as of Tuesday had yet to issue a final ruling.

Kaardal said the Democrat Party is pushing expanded qualifications for ballot status, too, in an attempt to make the presidential nominating process a coronation instead of a choice.

“The longer view is we really have to watch these introductions of state requirements for being a primary candidate because the establishment is trying to reduce choices,” the attorney said.

Party Power

Constitutional law expert Rick Esenberg said the federal authority challenge is a “live argument” even though he doesn’t necessarily agree with it.

Esenberg, president and general counsel of the Wisconsin Institute for Law and Liberty, said there is a body of law on the right of political parties to control the presidential nominating process. He noted the 1984 shakeup in which the Democrat Party of Wisconsin, pushed by the national party in an effort to eliminate cross-over voting, used a two-tiered caucus process in selecting delegates to the national convention. The longstanding primary was reduced to an advisory mechanism.

But caucuses, organized by parties and not administered by state election offices, are different political animals — as the storied Iowa caucuses show the world every four years.

Esenberg said the U.S. Supreme Court and the country are entering mostly uncharted territory.

“We don’t have a lot of experience of what any of this stuff means,” he said.

Who Decides Who Can Be President?

The Public Interest Legal Foundation asserts in court filings that the legal viability of the 14th Amendment’s Section 3, the foundation for the challenge, “is suspect” at best. The amicus brief in support of Trump, like others, argues that the presidency is notably absent in the list of specific offices to which Section 3 — the insurrection clause — applies. Section 3, the brief also argues, is not self-executing; Congress has not passed an enforcement law, so “no court has the authority” to enforce it.

But the brief, like other Trump-aligned filings in the case, makes no mention of the quo warranto law and its demands of federal jurisdiction.

Lauren Bowman, director of communications for the foundation, said she was not familiar with the legal argument. She said the Constitution spells out the requirements for the presidency, and “states can’t arbitrarily go through and decide who can be president.”

Bowman noted the U.S. Supreme Court’s 1994 decision blocking Arkansas from adopting congressional term limits as a case that raised similar separation of power questions. Arkansas’ constitutional amendment limited terms for the state’s members of the U.S. House and Senate. The question raised: Can states add to those qualifications for the U.S. Congress specifically enumerated by the U.S. Constitution? No, the 5-4 majority opinion found.

“The Constitution prohibits States from adopting Congressional qualifications in addition to those enumerated in the Constitution,” summarized case database Oyez.org.

That train of thought may be of interest to the Supreme Court justices hearing the Colorado ballot case.

But isn’t the federal jurisdictional argument just kicking the can down the road? Why not deal with the disqualification question now, before the election?

Kaardal insists the unprecedented legal question will ultimately end up in the D.C. court if Trump wins — even if the Supreme Court tosses the Colorado decision, as many constitutional law experts expect the high court to do.

“If Trump is elected president, he’s not an insurrectionist. It answers the question” via the voters, the attorney said. “The U.S. Supreme Court would be saying something illogical if someone was elected president but could be disqualified because of previous acts of ‘insurrection.’ If Trump wins the election and the Supreme Court ultimately sacks him there will be a reckoning of sorts.”