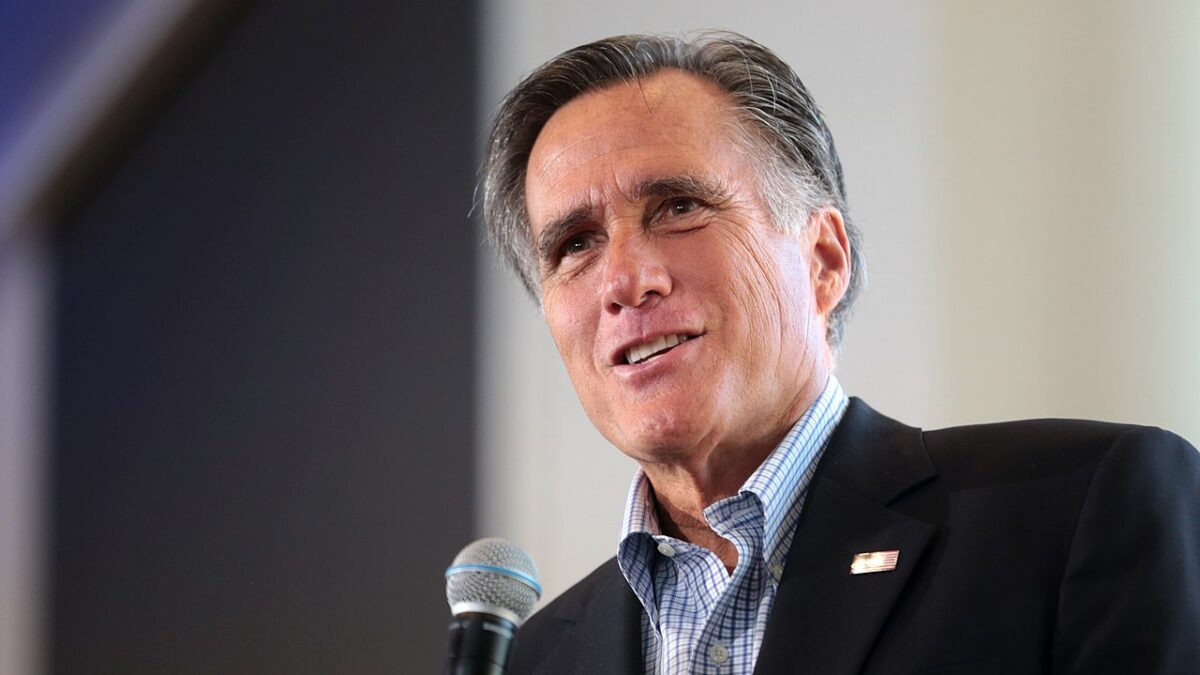

Last month, Mitt Romney announced he will retire from the Senate after one term. Romney, who is 76, cited his age. That was undoubtedly a major consideration for a guy with a platoon of grandchildren.

It’s also true that Romney is unpopular with Utah voters and had no real chance of reelection after becoming the most prominent elected Republican antagonist of Donald Trump. With Romney’s 30-year political career ending with a whimper, there would naturally be a forceful attempt to shape his legacy as something other than a failure.

Fortunately, Romney already made plans for this. The Atlantic’s McKay Coppins, also a practicing Mormon, was already beavering away on a Romney biography that was sure to be sympathetic. Sure enough, very soon after Romney’s retirement announcement, The Atlantic ran a juicy excerpt adapted from the prologue of the forthcoming book. While the excerpt was sympathetic to Romney, in some ways it defied expectations.

The tableau it paints of Romney is something of a caricature. A luxury condo in the Watergate was too painful a commute to the Capitol, and Ann Romney doesn’t like spending time in D.C., so he’s living alone in a $2.4 million townhouse on Capitol Hill. He passes the time by watching Ted Lasso reruns on his 98-inch television while eating salmon sandwiches slathered in ketchup because he doesn’t like salmon. (When it comes to food, the septuagenarian Romney, who has declared his favorite meat is “hot dog,” seems to have the maturity of a 7-year-old.)

When that doesn’t stave off the boredom, he invites over a reporter who will keep him company late into the evenings while he “nurse[s] a morbid fascination with his own death, suspecting that it might assert itself one day suddenly and violently,” brags about how his compulsive exercise habits are superior to those of his colleagues in the Senate, and breathlessly recites a litany of petty grievances about his fellow Republicans.

It had always seemed hard to reconcile Romney’s obsessive political drive with his charmed life and impossibly handsome façade without suspecting something slightly sinister lurking underneath. Now this Atlantic article reads like American Psycho: The Golden Years. I half expected the excerpt to end with Coppins nervously edging toward the door as Romney casually starts to fondle an axe and lay down plastic sheeting in the living room while cheerfully monologuing about what a tool Josh Hawley is.

Of course, there were other layers to this portrait of Romney. Coppins is a skilled writer, and I’d venture he’s one of the best at what he does, provided we’re clear that he works at The Atlantic, a media outlet with enough baggage that it is widely distrusted by anyone on the right.

But Coppins was also given a level of access to Willard Mitt Romney that was rarely granted to a biographer. The results would no doubt be revelatory. The only question is to what extent those revelations would be intentional, and to what extent Romney’s character would be revealed by how oblivious he is to how critics and ordinary voters might perceive him.

Believers of Convenience

Well, Romney: A Reckoning has finally arrived on bookstore shelves everywhere. On the surface, it’s a model political biography: a short recap of his early life, followed by a mostly chronological recap of his career. It’s a dream to read. The prose is concise and the story well-structured, and that is not a small compliment directed at Coppins.

On a deeper level, however, I’m still not sure to what extent Coppins is aware of the contradictions exposed and how they will be interpreted by anyone not already convinced Romney is a righteous crusader. The book is full of quotes and characterizations that, divorced from the calculating context, reveal Mitt to be haughty, weird, and willing to sell out even as he insists he hasn’t.

To have Mitt tell it, he’s always been dogged by irrational criticism: “Throughout my life there’s always been one person who just can’t stand me.” Here’s him trying to explain away why he’s off-putting to some people: “I was accused of being inauthentic. But in reality, that’s just who I am. … I’m the authentic person who seems inauthentic.” Here’s him summing up his opposition to estate taxes in his failed 2008 GOP primary bid: “It was one of those things you say because you don’t know what you’re talking about.”

None of this is especially damning for politicians, of course. People with ambition are often polarizing, normal well-adjusted people almost never run for office, and every politician finds himself uttering expedient rhetoric. What’s remarkable about Romney: A Reckoning is its exhaustive examination, and ultimate absolution, of Mitt’s behavior and motives while extending comparatively no grace to a cavalcade of politicians Romney singles out.

And it is an overly generous assumption that Romney deserves to be excused for a great many things. For instance, when Romney ran for president in 2008, he gave a defiant speech addressed to critics of his Mormon faith: “Americans do not respect believers of convenience. Americans tire of those who would jettison their beliefs, even to gain the world.”

Believers of convenience, you say? Here’s Coppins describing how Romney arrived at his pro-abortion position as a Senate candidate and later as governor of Massachusetts:

Now he wondered if there was any wiggle room in the Church’s teachings. As he studied the question, the incentive for rationalization was strong: He found quotes from church leaders who said abortion was ‘like unto murder’ — but they didn’t say it was murder. And while the Church didn’t take an official position on when the spirit enters the body, he discovered that a close reading of certain verses could lead one to conclude that it took place sometime after conception. He also seized on the Church’s twelfth Article of Faith, which declares a belief in ‘obeying, honoring, and sustaining the law.’ He ‘began to think abortion was a bit like polygamy,’ he told me later. Before Utah joined the United States, the Church acknowledged the illegality of polygamy and renounced the practice out of respect for the law. Abortion, he reasoned, had been legalized through Roe v. Wade — perhaps he had a similar responsibility to honor that?

Romney would later renounce his pro-abortion stance when he ran for president, but I don’t know where to begin with this, except to say it’s hard to respect this horrifyingly facile reasoning that makes a mockery of life and death, never mind that it shows Romney twisting the beliefs of his church.

(Also, as an historical matter, the polygamy analogy is grossly misguided. In 1858, the Mormon Church engaged in armed conflict with federal troops over polygamy and proceeded to ignore multiple anti-bigamy acts Congress passed until the church renounced the practice as a condition of Utah statehood in 1896. As mentioned in the book, Romney’s own father, former Michigan Gov. George Romney, was born in 1907 into a Mormon polygamist community in Mexico where the residents had fled to dodge U.S. laws. Subordinating church teachings out of strict respect for the law is not exactly a Mormon distinctive.)

Yet it’s remarkable how much of a vehicle this book is for Romney’s score-settling. It’s hard to blame Coppins for going along with this. The fact the book is Romney’s anti-Republican emetic was always going to be catnip for the wider press, and the marketing is practically on autopilot: “Mitt Romney’s Sickest Burns: Book Reveals Harsh Views of Fellow Republicans,” reads The New York Times headline.

While it’s fairly legitimate to bemoan that post-Trump Republican politics are defined by personal insults, as the book demonstrates, Romney isn’t just some guy caught in the middle of all this name-calling and trying to fight his way out with his honor intact. In fact, many of the beefs described herein predate or stand outside issues related to Trump.

Throughout the book, Romney is relentlessly contrasted as the one serious and sober Republican in a party defined by self-interested clowns. Even though Romney dominated the 2012 GOP primary, he still bemoans how “his inability to consolidate the support of his party — especially in the face of such unimpressive opponents — was humiliating.” Romney was, of course, up against the likes of Rick “a dimwit” Perry and Newt Gingrich, who is in Romney’s telling “a smug know-it-all.”

Never mind that Perry was a three-term governor of Texas, and the public impression of him as a “dimwit” largely rests on a debate gaffe that was far less damning than the gaffe that felled the presidential ambitions of Mitt Romney’s father, an episode that haunted Romney. Despite the moral failings in his personal life, Gingrich was a former speaker of the House and architect of one of the biggest congressional victories in American history.

By contrast, in 2012 Romney was a one-term governor who’d lost two of the three races he’d run in, and his major legislative accomplishment — taxing people who didn’t have health insurance — was cited as a template by the very incumbent Democrat president Romney hoped to unseat when he passed Obamacare, the most hated piece of legislation in a generation. Certainly, Romney’s opponents aren’t above criticism, but the idea that Romney was self-evidently superior to his opponents all along is pure arrogance.

The Lone Righteous Republican

Elsewhere in the book, it does not spare any contempt for the evangelical leaders who often play a role in Republican politics. Romney tried to play nice with them and obviously never felt welcomed.

Perhaps here’s where I should lay my cards on the table. I was a fifth-generation Mormon and, having grown up in the church, I can tell you anti-Mormon bias is a very real phenomenon. (In fact, my grandmother’s family genealogy website is so gloriously detailed that I can tell you Mitt and I are distant relatives.)

Further, as an adult convert to Lutheranism, my church’s belief in Two Kingdoms theology is somewhat accurately summed up by the apocryphal Martin Luther quote, “It is better to be ruled by a wise Turk than a foolish Christian.” I have zero problem voting for Mormons, and I’m certain I share Mitt’s wary approach to evangelical leaders who actively court political influence.

But that doesn’t mean you can brush off questions of religious differences as unfair, either. Mormons, for instance, do not believe in original sin, and whether men are inherently self-interested and sinful is not exactly an issue incidental to basic conservative political philosophy.

Instead, the approach to handling these issues in the book often comes off as hubris; Romney is again portrayed as more devout and sincere than so many of his critics. This is typified by an anecdote: Jerry Falwell questions Mitt about why Mormons don’t believe in the Christian conception of the Trinity, and instead believe there are three distinct entities. Romney allegedly gets Falwell to admit “most people would agree with you.”

Although I don’t have too much regard for Falwell’s religious bent, I have a hard time imagining that exchange went down quite the way it is presented. Even if it did, it’s hard to imagine a heretical belief would be excused simply because a large number of Christians mistakenly believe it.

Indeed, the tenets of his faith, Romney’s devout adherence in the form of prayers and blessings, and his interactions with the “prophets, seers, and revelators” Mormons believe lead their church are brought up so often in this book the cumulative impression is that Mitt’s faith is the reason he can be anointed the Lone Righteous Republican. I don’t think that was intentional. It’s just that as two high-profile Mormons in politics, Coppins and Romney are so used to doing PR for the church they didn’t know when they crossed the line between helpful and harmful.

Lest you think I’m being uncharitable in my interpretation, I would note that the review of this book in The New Yorker — a periodical not exactly known for respecting conservatives or traditional religious expression — is insultingly headlined, “Did Mitt Romney Save His Soul?” It’s also not exactly subtle in its conclusion that Romney’s salvific fate is tied to his willingness to become “one of the few in his party willing to criticize Trump’s excesses.” And boy, is it laid on thick:

His church teaches him that, one day, he will stand before God and face an accounting, for his thoughts, words, and works. He will have to explain his time in politics — the positions he took, the compromises he made, where he chose to stand firm. If Romney is at a loss, he might bring along Coppins’s record of his reckoning.

In any event, the idea of this book as a testament to Romney’s works-righteousness is somewhat amusing, because it also details feuds with prominent co-religionists. There’s a detailed recounting of more than two decades’ worth of petty swipes between Romney and former Utah Gov. Jon Huntsman Jr. and his billionaire father, neither of whom are hardcore Trumpy conservatives.

Then there’s Utah’s senior senator, Mike Lee. Romney doesn’t like Lee for the obvious reasons — like most in his party, Lee came around to supporting Trump, and Lee once called a bill Romney supported an “orgiastic convulsion of federal spending.” But then there’s this:

Though Lee was technically Utah’s senior senator, few in the state — or the Senate — thought of him that way. As a former presidential nominee, Romney had all the name recognition and the gravitas. He was Mitch McConnell’s first call on any Utah-related issue, and everything he said seemed to attract national media coverage. At six foot two, he even physically towered over his colleague. ‘Maybe,’ Romney mused to one confidant, ‘he just can’t stand being in my shadow.‘

I don’t feel compelled to litigate Lee’s political career, except to say that I can confidently say his deep knowledge of the Constitution and American history commands respect among peers in the Senate. The suggestion Lee doesn’t agree with Romney because he literally doesn’t see eye to eye with him is so juvenile it can hardly be defended as an offhand comment.

I don’t know what purpose it serves to be recorded for posterity in a book that some are grandiosely suggesting Romney “might bring along” to “stand before God and face an accounting.” In the meantime, I would suggest the rest of us bring along an airsickness bag.

‘I Feel the Same Way’

There are still more slights to catalog against Ted Cruz, Marco Rubio, John Kasich, Hawley, Bobby Jindal, Rick Santorum, J.D. Vance, Ron DeSantis, Mike Huckabee, Chris Christie, et al., but they are for the most part drearily predictable criticisms. In any event, you can read a more exhaustive accounting of Romney’s “sickest burns” in The New York Times. At this point, it’s far more interesting and insightful to take a look at who Romney respects, rather than who he doesn’t:

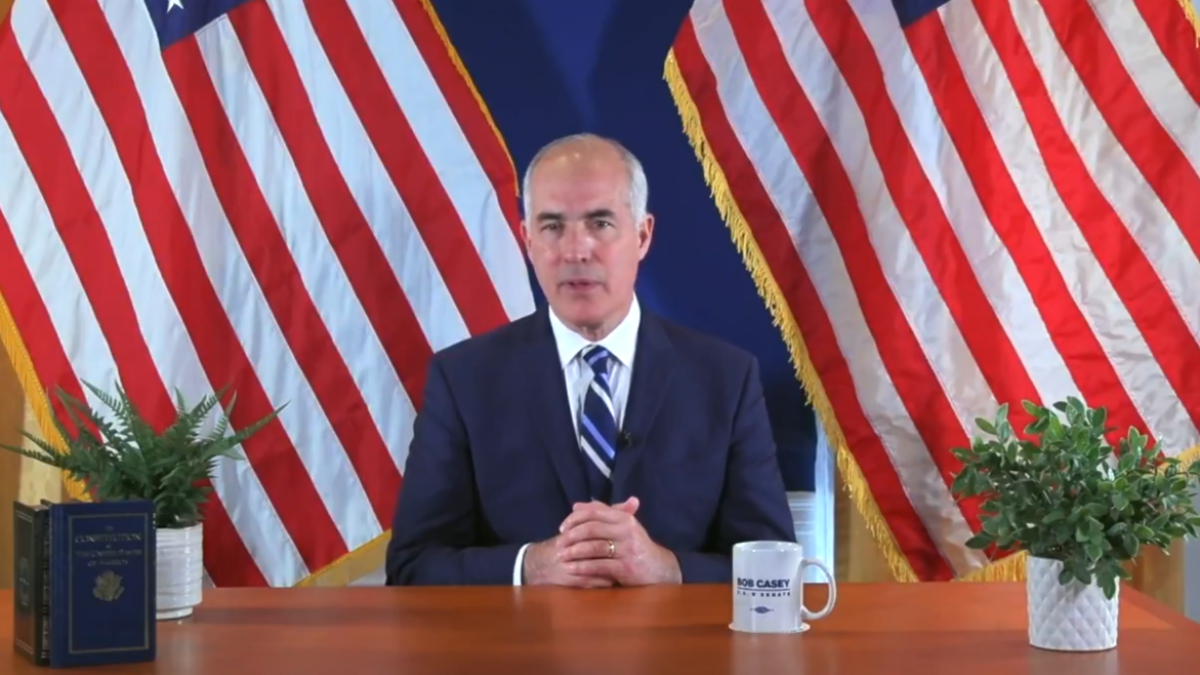

At a moment of rising authoritarianism at home and abroad, when the country’s founding ideas of democracy and self-governance were suddenly up for debate, Romney and Biden seemed to recognize in each other a shared set of values that transcended normal politics. …

One Sunday morning, Romney was sitting in church when the number for the White House appeared on his phone. He climbed over the grandkids who were sitting next to him in the pew and took the call in the foyer. It was the president.

‘I just wanted to call and tell you that I admire your character and your personal honor,’ Biden said. ‘We disagree on a lot of things, but I think highly of you as a person.‘

Romney, taken aback by the out-of-nowhere compliment, responded in kind. ‘I feel the same way.‘

I’m sorry, but what exactly about Joe Biden does Mitt Romney think highly of? I hope it’s not his current performance as president. This is a man who got busted for plagiarism in law school and as a senator. A politician who once made up the fact he got an award from segregationist George Wallace and tried to win over a crowd in Alabama by telling them Delawareans were “on the South’s side in the Civil War,” but later had the temerity to tell a black audience that Romney was trying to “put y’all back in chains.”

Romney apparently feels Biden is simpatico in his concern about “rising authoritarianism.” Meanwhile, Biden’s DOJ is arresting people for protesting against abortion, labeling parents terrorists for objecting to lesson plans that look like they were authored by Mao Tse-Tung and Larry Flynt, and investigating Catholics for the crime of going to Latin Mass.

Biden has repeatedly lied about the death of his own son and his wife in order to get political sympathy, and even The Washington Post stripped the bark off him for how selfishly he handled the families of the soldiers who died in his disastrous Afghanistan withdrawal. Romney thinks highly of Biden, but wants it known he disdains a squared-away fellow Mormon such as Lee?

Of course, one reason Romney might think highly of Biden is that he’s dangerously out-of-touch, to the point he’s unaware of the most basic facts pertaining to Biden’s corruption. Romney was the sole Republican to vote for Trump’s first impeachment, and this section of the book is replete with examples of Romney acting aghast that his Republican colleagues responded to the impeachment case against Trump in a political fashion, rather than examining the evidence against Trump and acting as an impartial jury, as Romney insists that he did. But I’m not sure Romney had a grasp of the most basic facts of the impeachment, based on this exchange with Sean Hannity:

Next, Hannity demanded to know why Romney wasn’t more outraged by the Burisma scandal. Romney — who didn’t spend enough time in the conservative media bubble to know the shorthand for Hunter Biden’s allegedly corrupt dealings with a Ukrainian energy company — responded by asking, ‘What’s Burisma?’ Hannity exploded: ‘How do you not know what Burisma is?‘

“Conservative media bubble”? Huh? Hunter Biden’s corrupt payoffs from the Ukrainian gas company were not a small story, even in the legacy media. In fact, I count 22 mentions of Burisma on The Atlantic’s website all in the months leading up to Romney’s impeachment vote. (Additionally, former CIA official Cofer Black — the national security adviser to Romney’s 2012 campaign — served on Burisma’s board alongside Hunter Biden.)

Burisma was not an incidental matter, because one potential defense of Trump asking Ukrainian president Zelensky to look into Hunter Biden’s shady million-dollar-a-year deal with the Ukrainian gas company was that Biden might, in fact, be implicated in actual foreign corruption. And whether the optics of a president investigating his partisan opposition are bad or not, that was exactly the precedent set in 2016.

The results of that investigation are pretty well-established: Obama and Biden were both aware of the bogus collusion investigation into Trump, while the FBI went around manufacturing evidence to get FISA warrants to spy on Trump and running down leads compiled in an outrageously inaccurate “dossier” bought and paid for by the Hillary Clinton campaign.

In the first impeachment that Romney endorsed, House Democrats took the unprecedented and suspicious step of interviewing all the witnesses in Trump’s first impeachment trial, save the first one, behind closed doors. Procedural rules put in place meant House members were under threat of ethics charges if they discussed what was said. That was almost certainly to keep Republicans from publicly asking questions about Biden’s corruption.

Biden then skated through the election brazenly lying about having no contact with Hunter Biden’s business dealings. We now have photos of Biden dining in Georgetown with Hunter’s business partners from that obscure company Burisma, all while the vice president was the White House point man on Ukraine policy. Then there’s the personal testimony from Hunter’s business partner that Joe Biden was being cut in on deals being struck with China. For his sake, I’m just going to assume that if Romney understood a fraction of this, he wouldn’t think highly of Biden as a person or consider his impeachment vote the result of a man who studiously examined the evidence.

But ignorance still doesn’t explain how Romney would treat so many Republicans unsparingly and then turn around and approach Democrats with the naivete God gave trout. Here’s how Romney responded to McConnell’s assertion that the House Democrats acted politically when they voted to impeach Trump:

‘We have good arguments to oppose [Trump’s] removal,’ he told his aides. But it was disingenuous to assert that the entire Democratic Party had been plotting impeachment from the moment Trump took office. ‘Mitch knows better.‘

Disingenuous? The Washington Post ran an article headlined, “The campaign to impeach President Trump has begun” the day Trump was inaugurated. House Democrats first introduced articles of impeachment against Trump in 2017 and two more times before Trump’s first impeachment, all for trivial reasons.

And elsewhere Romney and Coppins simply fail to fact-check. The obligatory mention of Charlottesville is as bad as you would expect: “The next week, when Trump was asked at a press conference about the violence, he said there were ‘very fine people on both sides.’ Romney, appalled, wrote on his list, ‘President’s equivocation/incitement of race/bigotry.’”

Of course, Trump never made that equivocation. When he referred to “very fine people on both sides,” any fair reading of his remarks recognizes that he was talking about those participating in the broader debate over tearing down historical statues.

Elsewhere in those same remarks he specifically condemned the violent neo-Nazis in Charlottesville, so it’s simply not fair to say he was praising them. Even CNN hosts have admitted as much. At most you can ding Trump for not being as clear in his rhetoric as the moment called for, but then again, Romney is proudly publicly identified with a church that didn’t allow black people to hold leadership positions until he was 31 years old. Perhaps before labeling Trump racist, he is owed a modicum of the grace Romney’s been extended on that matter.

And then there’s this astounding bit, which I simply can’t believe made it into the book: “On April 23, Trump mused during one of his briefings that perhaps Americans should inject themselves with bleach as a treatment for COVID-19.” Trump, of course, never said “Americans should inject themselves.” The undersecretary for science and technology at the Department of Homeland Security presented a study showing disinfectants would kill the Covid-19 virus, which prompted Trump to unhelpfully spitball about the role disinfectants might play in developing medical treatments for Covid.

It would be “interesting to check” if “there is a way we can do something like that by injection inside, or almost a cleaning” before later clarifying “it wouldn’t be through injections, we’re talking about almost a cleaning and sterilization of an area. Maybe it works, maybe it doesn’t work.” Even the usually odious media “fact checkers” admit the bit about people injecting themselves with disinfectants is false: “Despite Trump’s dubious, conjectural and inarticulate comments, he did not directly suggest that people inject themselves with disinfectant.”

It should have been enough to insist that the lack of clarity and general cluelessness in Trump’s remarks that day were a good example of how he mishandled a major public health crisis in a way that is dangerously unacceptable for a president. Yet by the end of the book we learn Romney doesn’t just believe Trump told people to inject themselves with bleach, he’s heavily invested in self-justification based on a myth:

He nursed a particular fantasy in which he devoted an entire debate to asking Trump to explain why, in the early weeks of the pandemic, he’d suggested that Americans inject bleach as a treatment for COVID-19. To Romney, this comment represented the apotheosis of the former president’s idiocy, and it still bothered him that the country had simply laughed at it and moved on. ‘Every time Donald Trump makes a strong argument, I’d say, ‘Remind me again about the Clorox,” Romney told me. ‘Every now and then, I would cough and go Clorox.‘

To be clear, defending many of Trump’s remarks and much of his conduct is a fool’s errand, one I don’t typically care to engage in. I did not vote for Trump in 2016 and only did so in 2020 because it seemed obvious enough a Biden presidency would be a world-in-flames disaster, an assessment I do not revel in being right about.

But that just makes it further mystifying, given all the legitimate things Trump and Republicans could be criticized for, why is so much of what animates Romney petty at best and untrue at worst?

It’s even more bizarre when you consider this is the result of Romney uncritically swallowing establishment media narratives, years after his run for president where the same establishment called him racist, said he gave people cancer, and dubiously accused him of being a gay bully in prep school, as if it was somehow relevant to the presidential race. It’s recounted in the book that no less a figure than Bill Clinton tells Romney that The New York Times — where columnist Gail Collins insinuated Romney abused the family dog more than 80 times — was unfair to him.

Yet that experience somehow imparted no skepticism about how others, let alone the next GOP presidential candidate, might be unfairly treated by the media? Similarly, does Mitt not recognize that the media were rendered powerless to rein in Trump largely because they eviscerated their credibility with Republican voters by libeling him?

Regardless, one thing is very clear. If the portrait of Romney in this book is accurate, no one as credulous and ignorant as Mitt Romney is entitled to this much sanctimony.

Normal Parameters

If I may say something positive about Romney, he does come off as clear-eyed about the failure of his 2012 campaign and his role in it. In particular, he beats himself up quite a bit for his infamous comment during the campaign that “47 percent” of Americans “believe that they are victims, who believe the government has a responsibility to care for them, who believe that they are entitled to health care, to food, to housing, to you-name-it.”

It’s good that he recognizes the bootstrapping condescension of establishment Republicanism was a losing message, even if he’s unwilling to recognize that he has that in common with Trump.

But in other key respects his 2012 revisionism is baffling. “I vastly overstated how bad [Obama] was for the country and the economy,” Romney says. “I think what presidents accomplish by virtue of their personal character is at least as great as what they accomplish by virtue of their policies.”

However, there’s been an exceptionally divisive hard-left cultural lurch Obama enthusiastically endorsed that I can’t imagine Romney agrees with. Does Romney really not grasp how incredibly destructive, say, Obama’s decision to force schools to allow men into high school women’s bathrooms has been?

Further, we can certainly compare economic and foreign policy track records before, during, and after Trump and honestly conclude Americans were safer and prospered more under Trump by many basic metrics. Romney is no doubt underestimating the effect of good policy and, at a minimum, overestimating Obama’s character.

But if we do accept that character is supreme, and I do agree it is a very important characteristic in political leaders, it’s also true that nobody’s perfect. This naturally raises the question of what levels of character deficiencies are acceptable to Romney, since Trump is clearly over the line. And this book contains an answer that explains a lot. “Hillary Clinton is wrong on every issue,” Romney told a crowd at the Aspen Ideas Festival, “but she’s wrong within the normal parameters.”

Indeed, the concerted attempt over decades to redefine the likes of Hillary Clinton’s political career as falling within the “normal parameters” is exactly how we got Trump. On issue after issue, voters were told to swallow the establishment spin excusing the toxic behavior of anointed elites who disregarded the needs of ordinary people.

Voters were told to be appalled by the crass fraud of Trump University and accept that the Clinton Global Initiative was something other than a nine-figure shakedown operation. It was intolerable Trump had extramarital affairs and supposedly broke campaign finance laws paying off a porn star, but Hillary Clinton owed her career to claiming that those objecting to her more talented husband using state troopers as pimps, defiling the Oval Office, and jetting off to Jeffrey Epstein’s pedo island were part of some “vast right-wing conspiracy.”

We were supposed to be gravely concerned about a ginned-up deep-state investigation into Trump, while FBI Director James Comey goes on television and invents a nonexistent legal rationale for why Hillary wouldn’t be charged for intentionally mishandling classified documents, obstructing the investigation, and destroying evidence. The fact that Romney, along with so much of the D.C. establishment, was invested in the idea there was a clear ethical choice in 2016, when voters had lots of good reasons to see it differently, says volumes.

Now maybe all of this ire directed at Trump and just about everyone else would be much more tolerable if it were contrasted with a winsome and compelling vision for American politics that takes into account the rifts Trump exposed between the political establishment and voters. Instead, Romney’s post-Trump career is explained away with a farrago of rationalizations for why Romney seriously considered Trump’s offer to make him secretary of state in spite of his loathing of the former president, as well as a frequently unconvincing account of his quixotic motives during his time in the Senate.

It’s further hard not to notice, as the book winds down, that Romney places himself at the center of a lot of delusional plans to stop Trump that would also have the added benefit of presenting himself as America’s political savior. In 2016, he considered running with Ted Cruz against Trump; Romney considered running as an independent in 2020 on a ticket with Oprah Winfrey (Oprah denies this, for what that’s worth); while in the Senate, he pitched Joe Manchin on the idea of starting a new political party; and when he explored a 2024 run for president, Kyrsten Sinema was “high on the list” of potential running mates. Because embracing a bisexual Democrat who left the Mormon church and refused to be sworn into the Senate by putting her hand on a Bible really speaks to Mitt’s commitment to showing Republican voters that character reigns supreme.

I’m honestly at a loss here. I’ve been covering Romney off and on for nearly 25 years, and I know several people who have interacted with him and his family and have nothing but glowing things to say. Given my own Mormon background, I had always felt something of a kinship with the man (literally, it turns out). I have publicly defended him in print dozens of times and don’t regret what I said. I’m still inclined to like and respect him.

But for a lot of readers, the story of Romney turning on his political party after briefly being their standard bearer is simply confirmation of their long-held belief that the political opposition is wicked. I don’t want to believe this book exists merely because Mitt craves barking-seal approval of congratulatory texts from George Clooney and all the other influential people who used to hate him. But there’s also nothing in this book that suggests any ideological constancy on his part. The only throughline is bitterness directed at almost everyone who got in his way.

In the epilogue, Coppins claims Romney’s “rationalizations fascinate me because they’re so common in Washington.” However, the line between rationalizations and delusions is mighty thin at times in this book, and Romney’s judgments can’t always be explained away with Coppins’ borderline-absurd attempts at providing favorable context for Romney’s judgments.

(E.g. Romney’s understandable aversion to Trump’s immigration rhetoric is undercut by Coppins taking the extra step to wave away the entire issue by informing us “right-wing media churned out baseless stories claiming … [immigrant caravans are] a Trojan horse for murderous cartels,” even though The New York Times agrees illegal immigration is “multi-billion-dollar international business controlled by organized crime, including some of Mexico’s most violent drug cartels.”)

In the end, it’s impossible to explain away this many recriminations as well-intentioned, and there’s a tragic irony in the fact that the man who made Romney this way thrives on uncharitable rhetoric. The difference is that the case for Trump is best expressed as a transactional one based on his broader economic and foreign policy accomplishments as president, and however corrosive Trump’s personal traits may be, there are many fewer public justifications being offered for them.

By contrast, until I read Romney: A Reckoning, it had never occurred to me that the most obvious reason Romney’s political career petered out in a hail of grievances is that he’s turned into — and it pains me to say this about an otherwise exemplary man — kind of an asshole.