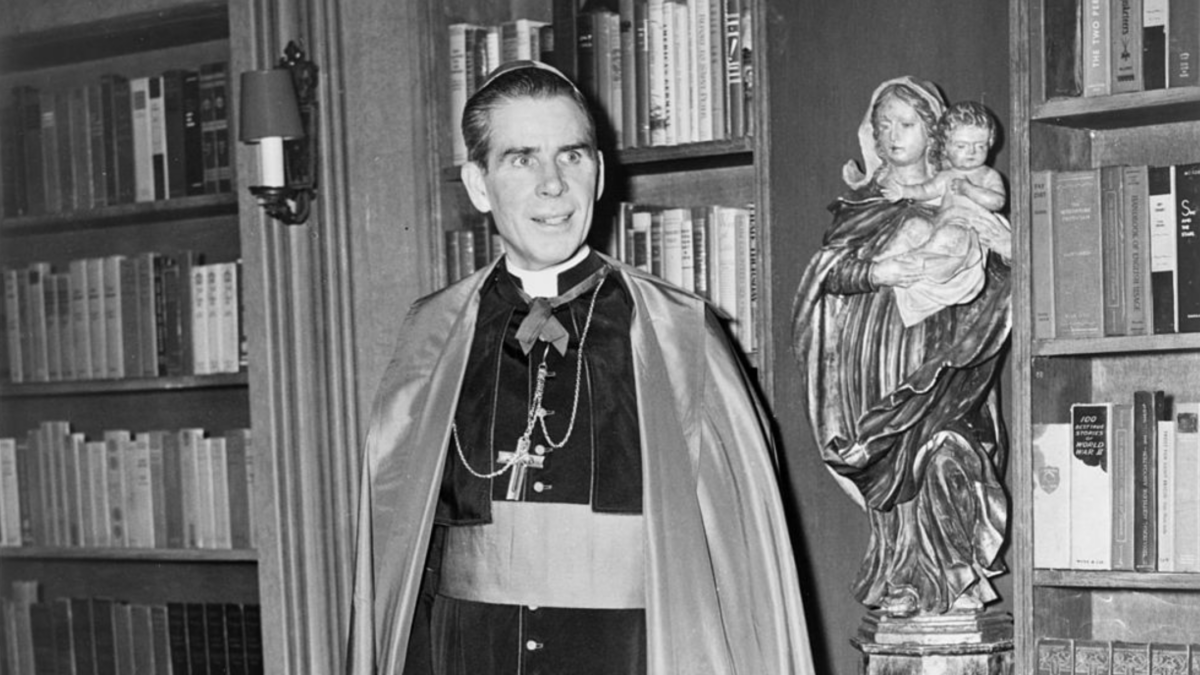

Archbishop Fulton Sheen was America’s public face and voice of Catholicism during the maelstrom of the Second World War and into the early decades of the Cold War. A tall, imposing, and charismatic Irish-Catholic bishop, Sheen was an academic turned cultural commentator through the advent of radio, television, and mass media. In a new edited anthology of his radio lectures and writings during World War II, aptly titled “War and Peace,” Sheen’s remarks on the cultural, political, and spiritual crises of America are extremely prescient and could easily be read as commentaries on the current struggles of the 21st century.

Over the past decade, an increasing worry about the proliferation of cancel culture and relativism within American education has come to the fore. This, however, is nothing new. Likewise, lamentations on the spiritual decline of Americans have garnered attention from faithful and unbelievers alike. This also is nothing new. Moreover, the malaise of democracy and the fear of growing despotism and dictatorship has become a great concern for American political life. This, too, is nothing new.

All the crises we are currently living through were apparent to Fulton Sheen in the 1930s and 1940s as America struggled against communism, fascism, educational and moral relativism, social upheaval, and concern about the future of democracy and liberty.

In 1941, Sheen wrote, “secular college and university education teaches in one form or another that there is no such thing as evil or guilt, that there are no absolute standards of right and wrong, that right and wrong depend entirely upon one’s point of view.” While such a statement may sound like an indictment against today’s flailing and failing university system, reading Sheen’s insights into the crisis of moral education allow one to recognize the inherent contradictions of the revolutionary spirit. Sheen goes on to say, “On the other hand, the very products of this unmoral education are now, in the domain of politics, pointing fingers at Hitler and Mussolini — not at Stalin, of course — and saying: ‘They are wicked; they are wrong; they are evil.’”

Part of this contrast between relativist moral education and the politics of moral outrage and rhetoric is that political conflict affirms the reality of moral sentiments. We use the language of right and wrong alongside goodness and evil in politics. Yet our own educational system and prevailing philosophical attitudes affirm the opposite. This leaves us at an impasse of deep confusion and chaos. For our intellect has been indoctrinated to think there is no evil. Yet our hearts, when witnessing political events, are roused to a sense of moral action.

The advance of relativist moral education and the moral malaise that has swept a lot of American society lies with the intelligentsia and their revolutionary followers. Sheen, himself a highly educated man, a recipient of a doctorate, and a well-received scholar of Saint Thomas Aquinas, seems like an odd defender of the masses while being a critic of the educated elite. He was. And in many ways, he prefigured the rise of the educated defenders of the masses against their stifling elite critics.

“Wherein lies the future of America?” Sheen questions. “The problem is concerned with a choice between two classes: The intelligentsia and the masses.” He goes on to say, “Our conclusion will be: The future of a better America is in the masses and not in the intelligentsia, for we are witnessing in our national life what might be called the Betrayal of the Intellectuals, or the Treason of the Educated.”

Who is the intelligentsia? For Sheen, they are “those who deny absolute standards of right and wrong, make truth and error relative to a point of view, and completely ignore the will and its discipline in the training of youth.”

Who are the masses? The masses are the common Americans: men, women, and children of the family who affirm the belief in God, good and evil, and the necessity of sacrifice, “The masses are the hope of the future for the potentialities of sacrifice, which is essential to the preservation of a nation in time of trouble.”

Thus, the future of America is shaped differently by these two great classes, these two great forces, not only at war with external enemies (communism, fascism, and Nazism) but also with each other since moral character is learned and trained and never a continuous given. America will either be a God-believing, moral, and sacrificial nation girded by the pillars of faith and family or become a godless, amoral (relativistic), and hedonistic nation that surrenders everything to state bureaucracy managed by the intelligentsia.

This loss of faith, family, and sacrifice for Sheen was of great concern because the survival of democracy — which is nurtured on faith, moral virtue, and sacrifice as the Founding Fathers knew — was a weakling compared to the totalitarian regimes of Europe and the Soviet Union, which could call upon their disciples with the mystical appeal of eschatological utopianism inherent to their ideologies. “Totalitarian states,” Sheen writes, “can more readily appeal to sacrifice than some democracies, for having imbued their people with a diabolical mysticism and having infused them with a false fervor, they are ready to deny themselves for a future glory.”

This diabolical mysticism and ability to project a utopia into the future that slaves of totalitarian regimes sacrifice for stands in contrast to the moral relativism and weakness within democracies fostered by the amoral education of the intelligentsia. “But when democracies lose the spirit of religion,” Sheen writes, “they have no fulcrum for self-sacrifice.” Sheen also notes, “The preservation of America is conditioned upon discipline and self-sacrifice, but since these are inseparable from religion and morality, the future of America depends on Americans’ attitude toward God.”

The irony of Sheen’s insights and appeals was that he was proven right during the Cold War. American revival in faith and the family after the Second World War gave America the courageous spirit to stand up to global communism after defeating fascism and Nazism when most of Europe grew weak and lost their faith. It was the moral backbone of the American masses, not “the best and the brightest,” that made the sacrifices to defeat the Soviet Union and keep the world free from communist oppression. But once the Cold War ended and the Soviet Union was defeated, the same problems that Sheen saw in the 1940s reappeared.

Today, we are still in the throes of the same crisis that Sheen fought against. Creeping totalitarianism threatens democracy. Godlessness and amorality plague American society, and with its advances, the backbone of liberty withers. The masses once again find themselves in a brutal contest with the American intelligentsia, who dominate schools and media and are viciously hostile to their way of life. Despite the renewed proliferation of relativism as an intellectual fad, our political rhetoric retains that moral sentiment of right and wrong, good and evil.

Within the pages of “War and Peace” are nearly 400 pages of intellectual and spiritual gold. The problems we are facing today are not new. They weren’t necessarily new in Sheen’s time either. Every generation must learn the sacrifices necessary for the preservation of liberty. Every generation must contest good and evil despite what their sophistic professors told them. Every generation must do what Jacob did: wrestle with God, knowingly or unknowingly. That wrestling with God affects the future of our world — for better or worse. Let us remain hopeful, as Sheen was hopeful, that goodness prevails.