Most people who have never heard of Zhao Wei likely never will now. Zhao was once a megastar in China’s entertainment industry, starring in many hit TV shows and films, such as “Red Cliff,” in the last two decades.

The 45-year-old actress was also known as a director, businesswoman, and investor. She had more than 85 million followers of her fan page on the microblogging platform Weibo. But in a matter of days at the end of August, Zhao “vanished” from China’s digital world.

The Chinese Internet was scrubbed of her interviews, movies, and TV shows. Searching for her on Weibo today, you will find nothing.

Zhao has never been officially charged with any wrongdoing, although some suspect her disappearance has something to do with her close relationship with Jack Ma, the outspoken founder of China’s largest e-commerce company, Alibaba. Ma himself disappeared after he criticized the Chinese government’s regulations on technology companies in October 2020.

Several other big-name celebrities vanished around the same time as Zhao. There are many indications that their digital disappearance results from Beijing’s latest crackdown. Beijing has ordered Chinese media companies not to select male actors or guests who appear “too effeminate.”

The Tea Leaves of Another Cultural Revolution

Within a day or two of Wei’s disappearance, a blog applauding the government’s actions went viral in China. It predicates “the red has returned” and “a profound transformation or revolution” is underway in China. The blog was written by Li Guangman and posted on WeChat, another Twitter-like Chinese social media platform.

Since Li is not well-known in China, few would have paid any attention to him in normal circumstances. Even in China, a fervent far-left Maoist like Li is in the minority. Yet something curious happened: all major state media, such as People’s Daily and other social media platforms, re-posted Li’s blog with the same headline: “Everyone Can Sense That a Profound Change is Underway!”

Welcome to Xi’s China’s Cultural Revolution 2.0.

Mark Twain famously said, “History doesn’t repeat itself, but it often rhymes.” That seems to ring true in Communist China. Xi Jinping, the leader of the Chinese Communist Party, has recently been cracking down on sectors such as tech, education, and entertainment in an attempt to reshape China’s culture and the economy more in line with socialist ideology.

Given that the Chinese government has the media industry under firm control, major state media would not have re-posted a blog from an unknown figure unless they received direct orders from someone higher up in the Chinese Communist Party’s propaganda department. Therefore, people began to speculate: did someone higher in the CCP tell Li to write such a piece, or did Li write it on his own, but someone important liked it and instructed prominent media outlets to share it? Was the widespread sharing by party mouthpieces such as People’s Daily meant to test the public’s reaction or represent an official endorsement of his call for a red revolution?

Parallels with Start of Mao’s Cultural Revolution

People who are familiar with Chinese history know that one of the critical triggers of Mao Zedong’s Cultural Revolution was the publication of dazibao (“big character poster”) on May 25, 1966, by Nie Yuanzi, a student at Beijing University. The poster with oversized Chinese characters denounced professors and administrators for their embrace of Western bourgeois values and lack of revolutionary spirit. Although Nie wrote the poster herself, she probably received help or even orders from senior party leaders in Chairman Mao’s inner circle, because soon after Mao directed People’s Daily to re-publish Nie’s poster.

Three months later, Mao launched the Cultural Revolution. Borrowing phrases from Nie’s big letter poster, Mao claimed bourgeois elements had permeated every aspect of Chinese society, from the government to schools, factories, and other institutions. They sought to restore capitalism and the party’s ability to exploit people.

Therefore, Mao insisted that only ferocious class struggles could eliminate these counter-revolutionary elements and ensure China was on its correct path to a Communist utopia. What followed was a decade of chaos and destruction throughout the country and complete isolation from the outside world.

During the Cultural Revolution, an estimated 20 million people perished, including senior party officials Mao regarded as his political enemies. China’s economy was on the brink of a total collapse, and cultural sites, relics, and countless properties were demolished or ravaged.

The Cultural Revolution only ended when Mao passed away in September 1976, but its damaging effects have lingered long after. The movement has left a severe psychological scar on the minds of the Chinese people born before 1980. This is why, when major state media re-posted a blog that was full of Maoist slogans and calling for the return of “profound revolution,” people both inside and outside China started to wonder: is Xi going for a Cultural Revolution 2.0?

Xi Models Mao

Chinese officials rushed out statements to calm the public and ease foreign investors’ fears that history would repeat itself. A front-page editorial in People’s Daily claims, “Opening to the outside world is China’s basic national policy, and this will not waver at any point.” However, such reassurance offers little comfort because action speaks louder than words. There are simply too many similarities between Xi’s revolution and Mao’s Cultural Revolution.

Unmistakably, Xi models his leadership style directly after Mao. Xi brazenly embraced efforts to build a cult of personality last seen in China under Mao. There are songs including lyrics such as “To follow you [Xi] is to follow the sun.”

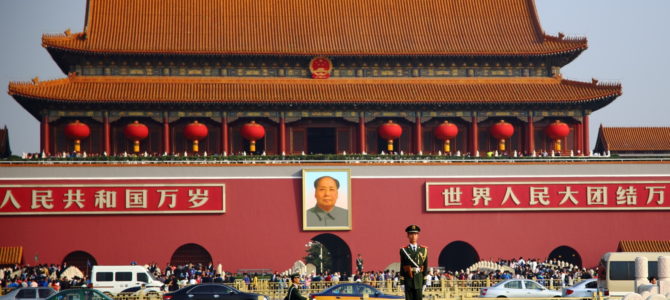

The party’s propaganda machine has also showered him with great titles: “Core of the Party” and “Helmsman of the Nation.” These were superlatives last used to address Mao. The entire nation has been called to “unite tightly around President Xi.” Like Mao’s, Xi’s portraits are ubiquitous. Like Mao’s “little red book,” the collection of Xi’s speeches and instructions has been a national bestseller and is compulsory reading even for schoolchildren.

Xi is a fervent nationalist and socialist who believes socialism and China’s national identity are inseparable. Xi demands absolute obedience and loyalty not only from his party members but also from the general public. That’s why under his rule the Chinese people have seen increased surveillance, censorship, and the worst crackdown on dissent since Mao’s Cultural Revolution.

On the cultural front, Xi has done more than just making a few celebrities “disappear.” Like Mao, Xi demanded culture to serve as the party’s propaganda machine and assist the party’s aim to turn Chinese men into masculine and patriotic socialists.

Xi has banned Chinese youth from playing more than three hours of video games each week. At the same time, the scale and intensity of “red education,” which promotes unyielding loyalty to Xi and the party, has reached a level last seen during Mao’s Cultural Revolution.

Revolutionary songs praising the Chinese Communist Party have become popular once again. Movies that glorify the party’s deeds during the Second Sino-Japanese War and the Chinese Civil War have become blockbuster hits.

Capitalism a Phase on Road to Socialism

Xi’s Cultural Revolution 2.0 has gone beyond reshaping China’s culture. On the economic front, Xi has been trying to roll back the four decades of economic reforms launched by Deng Xiaoping and continued by Xi’s predecessors. According to The Wall Street Journal, Xi’s objective is to “get China back to the vision of Mao Zedong, who saw capitalism as a transitory phase on the road to socialism.”

Like Mao, Xi has launched a campaign against private businesses in China, including scrapping Ant Group’s record-setting $36 billion initial public offering; imposing a $2.8 billion fine on Ant’s parent company, Alibaba; and banning China’s private tutoring companies from making profits, which practically wiped out the entire industry.

Xi’s most socialist move was when he rolled out a new policy aiming to achieve “common prosperity,” a fancy name that is really about the redistribution of wealth from China’s rich business owners (excluding party members, of course). Xi publicly talked about the need to “regulate excessively high-income groups” and how “businesses should return more of their profits to society.”

Such talk is reminiscent of Mao’s “land reform” in 1950, which forcefully took land away from landowners and redistributed it to landless, poor farmers. A few years later, the government took land away from poor farmers and has nationalized land ownership since then. “Land reform” turned out to be a smokescreen for the party to demolish private property rights.

Responding to Xi’s new “rob the rich” policy, fearful private businesses in China moved swiftly to demonstrate their party loyalty and willingness to “return more of their profits to society.” Alibaba announced it would invest 100 billion yuan ($15.5 billion) over the next few years into “common prosperity” initiatives, including supporting vulnerable groups. Other tech companies made similar pledges too. Xi’s shakedown of the rich has been enormously effective.

While Mao’s Cultural Revolution was primarily a domestic affair, Xi’s ambition is to have socialist China dominate in the new world order. Not surprisingly, Xi’s Cultural Revolution 2.0 has already had a significant impact on the rest of the world. Xi’s economic crackdown has already sparked several rounds of substantial global stock market selloffs, wiping out $1.5 trillion in the value of Chinese companies he targeted. International investors have suffered enormous financial losses.

The sooner policymakers and investors in Western democracies understand Xi’s ambitions and ideological drive, the better they can develop policies and strategies to protect democracies and everything we cherish from the harms of a determined socialist and his revolution.