Throughout the Stamp Act crisis of the 1760s — the “Prologue to Revolution,” according to the title of historian Edmund S. Morgan’s published collection of documents — the British North American colonists sent petition after petition to both houses of the British Parliament. These petitions frequently asserted the rights that the colonists possessed as British subjects.

According to the Resolutions of the Stamp Act Congress in 1765, the colonists were “entitled to all the inherent rights and liberties” due to them as “natural born subjects” of the British king. They possessed the same “rights of Englishmen” that had been possessed by British subjects since the time of Magna Carta. Among these rights was that of immunity to taxation without representation — the birth of the rallying cry that now constitutes just about all that most Americans can tell you about the American Revolution.

Most of the colonists at this time argued on the ground of the universally acknowledged geopolitical reality: the British colonies in North America existed under the British imperial constitution and within the jurisdiction of British political authority. They were British subjects with British rights.

Rights From God and Nature

Against this backdrop of pragmatic, predictable political debate, James Otis’s “The Rights of the British Colonies Asserted and Proved” stood out like an electric guitar in a classical string ensemble. Although Otis did acknowledge the legitimate political authority of Great Britain and its Parliament over the colonies, he imagined an entire realm beyond and underneath this geopolitical one.

He opens the discussion by describing someone searching after the “foundation of any of their rights,” stopping first at a “charter from the crown,” and then at “old Magna Charta,” until finally: “They imagine themselves on the borders of Chaos . . . and see creation rising out of the unformed mass, or from nothing.” Peering across this border throughout the pamphlet, Otis proceeds to trace the “rights of our fellow subjects in Great Britain” directly to “God and nature.”

Otis, according to contemporary accounts, suffered from mental illness in the later part of his life. Perhaps he was already losing his grip in 1763. But if he was crazy to imagine a parallel reality in which “God and nature” were the foundations for the colonists’ rights — both “black and white,” we might add — so, too, was Thomas Jefferson a decade later.

Jefferson’s “Summary View of the Rights of British America” similarly soars well beyond the politics of pragmatic reality and attaches the colonists’ rights to “God” and “nature,” raising the outlandish claim that the early colonists actually emigrated from England to begin entirely new political societies in North America. Jefferson’s then-ridiculous historical claims became political reality two years later, however, when his Declaration of Independence justified colonial independence on the basis of the twin pillars of his and Otis’s parallel reality: “the laws of nature and of nature’s God.”

Both Otis and Jefferson engaged in political action on the basis of a more expansive perception of reality than that of their contemporaries: a perception of a parallel reality that could not be directly sensed or experienced. They tried to convince the people of their time that the things that seemed most real to these people — things like British imperial political power or their traditional political rights — were actually less important or even less real than abstract principles like God and nature. Their politics of parallel reality was visionary without being utopian, and aspirational without being progressive.

Evidence of Things Not Seen

The parallel reality of a divinely created natural order was less a goal to be reached and more a standard already and always present. Aligning with this standard was not a historical inevitability but an ongoing practical task.

In highlighting aspects of reality that could not be directly seen, heard, or felt, early Americans like Otis and Jefferson were not just imagining things. Nor were they simply engaging in hyperbolic rhetoric. They were also engaging in a kind of premodern natural science, the kind that holds a more expansive view of nature as including not two, but four, constituent dimensions.

Aristotle had enumerated four causes of natural motion or change: material, efficient, formal, and final. The first two can be sensed directly, while the last two cannot. The “formal” dimension is most often associated with the soul, and the “final” involves concepts like happiness and, ultimately, religious beliefs about an afterlife. The formal and final dimensions, on this older, broader understanding, run like a parallel reality throughout the entire natural world. They are always present and powerful but exist beyond the reach of our physical senses. We ordinarily sense the world in 2-D, but it actually exists in 4-D. By attending to these additional dimensions in their political arguments, Otis and Jefferson weren’t “seeing things.” They were seeing more and further than their contemporaries, or the many sensible historians who have dismissed their ideas, could.

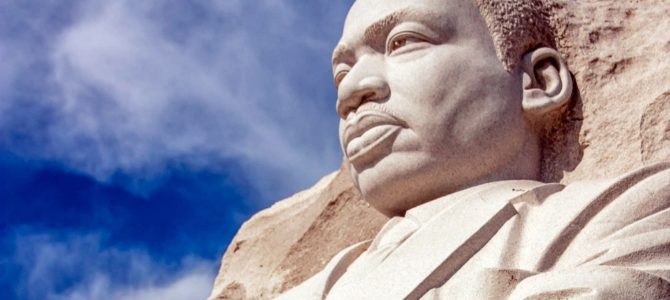

Martin Luther King, Jr. is most often associated with the high-flying, fluffy-and-fuzzy rhetoric that these sensible historians tend to ascribe to Otis and Jefferson. His best-known speech is about a “dream” — mellifluous, certainly; serious and sensible, most certainly not. Malcolm X is the hard-hitting, serious realist; King is the soft-headed idealist. A closer look, however, reveals a very different King: a King whose “dream” was not a sleepy look into the future but a clear-sighted perception of the waking world around him.

King’s dream was not only about an imagined future reality but also, and more profoundly, about a present reality that walks silently alongside and powerfully influences the one that we see. In line with the tradition of Otis and Jefferson, King consistently engaged in the politics of parallel reality.

This can be seen most clearly by carefully attending to King’s strategy of nonviolent civil disobedience. The common perception is that King’s strategy was basically the same as Gandhi’s, buttressed by Thoreau and then window-dressed with conventional American references to the Founding, Lincoln, and Christianity. Although Gandhi’s example was an important influence on King’s strategy, and Thoreau was an important influence on many nonviolent protest movements (including Gandhi’s), this common perception entirely misses the core of the strategy in King’s own eyes.

Eternal Law Runs Parallel to Human Law

King’s “Letter from a Birmingham Jail” is probably the most profound, thorough, and lengthy statement that King ever provided in explanation of his strategy of nonviolent civil disobedience. In it, King traces the lineage of this strategy through the Boston Tea Party, Socrates, the early Christians, and finally, all the way to the incombustible trio of Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego. King even quotes T. S. Eliot at one point. Gandhi and Thoreau? They don’t even merit a mention.

Instead, King relies on Saint Augustine, Saint Thomas Aquinas, Martin Buber, and Paul Tillich in his succinct explanation of the justification for civil disobedience: “A just law is a man-made code that squares with the moral law or the law of God. An unjust law is a code that is out of harmony with the moral law.” The “eternal law and natural law” run parallel to “human law” as real and essential components of law; to paraphrase James Otis, everyone sees human laws, but few trace their foundations to an unseen reality behind them.

Just as Thomas Jefferson and the American Revolutionaries justified their declaration of independence with reference to the “laws of nature and of nature’s God,” so King justifies his strategy of nonviolent civil disobedience with reference to “the moral law or the law of God.” In both cases, concrete political action is justified by an unseen, immaterial world in which God exists, sets things in order, and legislates for humanity.

This pattern continues in King’s other writings and speeches about his strategy and the philosophy behind it. Gandhi and Thoreau are mostly absent. In their place is a persistent emphasis on acting in light of physically imperceptible realities. At the outset of his 1958 essay “The Power of Nonviolence,” King admits that his philosophy “didn’t make sense to most of the people in the beginning.” It didn’t comport with their most familiar and direct experiences of life and of the world that they could see, hear, and feel regularly around them. “External physical violence” was something obvious, evident; nonviolent resistance, on the other hand, was an “internal matter” whose effects could not be physically seen.

MLK, Jr.’s Revolutionary Thinking

In the last speech of his life, ten years later, King related the encounters of protesters with Bull Connor in Birmingham, Alabama. Explaining Bull Connor’s tactics of setting dogs on the protesters and spraying them with fire hoses, King did not say that Bull Connor was an unjust oppressor, a racist, or even ignorant. In fact, he specifically noted Connor’s knowledge of “physics.” The point that King emphasized is that while Connor “knew a kind of physics,” he did not connect this knowledge to “the transphysics that we knew about.”

In an interesting twist on the biblical story of Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego that he had referenced in his “Letter from a Birmingham Jail,” King noted “the fact that there was a certain kind of fire that no water could put out.” After rhetorically transforming physical fire into spiritual fire, King did the same thing to the water: “If we were Baptist or some other denomination, we had been immersed. If we were Methodist, and some others, we had been sprinkled, but we knew water.” The physical water of the fire hoses became the spiritual water of religious baptism.

Viewing the resonances of Martin Luther King, Jr.’s thought with that of the American Revolutionaries in terms of the politics of parallel reality — instead of the conventional terminology of Christianity or natural law theory — shines much-needed light on crucial aspects of both.

First, it provides an essential supplement to Lincoln’s famous interpretation of the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution as primarily forward-looking. The aspirational quality of the phrase “all men are created equal” consists in the fact that the concrete, physical reality that we see does not match up with the parallel reality that we don’t see. This was as true in the moment Jefferson drafted the Declaration in 1776 as it was in the moment Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863 and, for that matter, in every moment between these and our current one.

“All men are created equal” is not forward-looking but an immediately present reality; we just think of it as forward-looking because we are looking forward to a time when our concrete, physical reality looks more like this parallel one.

‘Created Equal’ For All Time

Second, it helps us navigate the long-standing difficulty of trying to reconcile the moral principles that imbued the American Founding era with the starkly contrasting realities of African American slavery, Native American displacement, the political exclusion of women, and numerous other unjust practices of the time. Statements relating to religious belief (whether natural or revealed) or human nature — such as “all men are created equal” — are not statements about physical, tangible reality but rather about an immaterial, invisible parallel reality.

This is one way of understanding what Lincoln meant when he said that the Founders “did not mean to assert the obvious untruth, that all were then actually enjoying that equality. . . . They meant to set up a standard maxim for free society, which should be familiar to all, and revered by all; constantly looked to, constantly labored for, and even though never perfectly attained, constantly approximated.” Jefferson and the other Founders, in other words, weren’t talking about concrete, sensible reality in these statements of moral principle. Nor were they talking about the future. They were talking about a “constantly” present parallel reality.

Third, it simultaneously connects Martin Luther King, Jr. with a much broader, older philosophical-religious tradition and provides a simple, straightforward way of contrasting his outlook with that characteristic of Malcolm X and his followers. Martin Luther King, Jr. differed from Malcolm X in the content and centrality of his religious beliefs to his political activism, in his identification with the American political tradition going back to the Revolution, in his reliance on natural law theory, and in his indefatigable optimism (among other things).

All these elements can be comprehended under the heading of the politics of parallel reality — seeing a 4-D world rather than a 2-D one. The quarrel between King and Malcolm X was, in fact, a version of the one between Plato and Machiavelli: where Malcolm X typically emphasized the physical, “effectual” dimensions of reality, King was preoccupied with the immaterial ones that cannot be seen from inside the cave.

Martin Luther King, Jr. and British North American colonial leaders in the mid-eighteenth century similarly relied on a fusion of religious beliefs with philosophical principles to motivate political action. It was only by engaging in the politics of parallel reality that they were able to bring about momentous change in the part of reality that too often holds our focus.

In this way, the King-led African American civil rights movement of the 1960s was more like the American Revolutionary movement of the eighteenth century than it was like any other twentieth-century rights movement.

Republished from RealClearPolitics, with permission.