In response to the Wuhan coronavirus, state governors and local leaders have issued wide-ranging executive orders requiring closure of “non-essential” businesses. This affects churches, including imposing criminal penalties for noncompliance in some instances. Some churches have pushed back by simply holding mass services anyway, and several pastors — most prominently in Florida and Louisiana — have been criminally charged.

Many people are wondering, how is this America? Is this constitutionally sound when we have First Amendment protection?

Where We Came From

Our Founding Fathers recognized the inherent tension between protecting fundamental individual rights (such as religious liberty and freedom of assembly) that are God-given and pre-political but not absolute, and the necessary regulatory and enforcement power of government that is specific and limited. Necessary power is proper, because how could a government protect individual rights and overall health, safety, and welfare without the power to do so? But give a government too much power, and it will trample individual rights and liberty.

James Madison contemplated this paradox in Federalist 51: “If men were angels, no government would be necessary. … In framing a government which is to be administered by men over men, the great difficulty lies in this: You must first enable the government to control the governed; and in the next place oblige it to control itself.”

This paradox to balance government power and individual rights has been litigated throughout American jurisprudential history and always goes back to the U.S. Constitution. Our supreme law was shaped upon our founding premise: American individuals retain all our rights; government has limited powers through our consent.

So while this COVID-19 pandemic presents new facts and circumstances, the underlying principles are the same ones attorneys have analyzed since the founders argued about what specific powers to grant the government at the 1787 Constitutional Convention.

American jurisprudence has in general kept a good balance between protecting individual rights and preserving necessary powers for government. Our balance of powers has also recognized within our federalist system that state governments are closer to the people. Because of that, the federal government has fewer and very specific, limited powers.

The 10th Amendment provides the basis for the state government’s inherent police powers, which have been acknowledged by the judiciary to establish and enforce laws to protect the health, safety, and welfare of all people within the state’s jurisdiction. We’re familiar with examples of this authority in fire codes, food safety regulations, and the state criminal code.

Where We Are Now

Most states appear to be implementing stay-at-home orders through legislatively determined emergency powers granted to the governor. However, some states are attempting to impose orders beyond state constitutional authority.

In South Carolina, for instance, the executive must get consent from the state’s General Assembly to continue a state of emergency beyond 15 days. Virginia’s governor imposed a stay-at-home order until June 10, well beyond a reasonable definition of “emergency,” as even the federal government has provided guidance and recommendations for only 30 days beginning March 31. In Texas, litigation has already reached the 5th Circuit over what type of business is considered “essential,” and many people are concerned elective procedures such as abortion are considered “essential” in some states while church services are not.

This notion of deeming private business “essential” or not is probably the biggest challenge and constitutionally problematic issue in state and local orders. This is arbitrary, and it’s highly doubtful this action would pass constitutional muster. While government has inherent police power via the 10th Amendment, private actors have the right to equal protection via the 14th Amendment.

Government can determine essential versus non-essential workers within its own employees in the context of a shutdown, which we saw as recently as last year. But there is no constitutional authority on the federal or state level that allows government to subjectively determine who and what is essential for private workers, including during a national health emergency. States are issuing orders without providing complete criteria for how they are making these determinations. There is arguably no metric that could possibly satisfy constitutional scrutiny.

It’s alarming that some ongoing litigation concedes the threshold question of a government’s ability to determine essential private services, and instead only argues for a particular service to be included in the “essential” list. That threshold question should be challenged.

The courts regularly employ the “strict scrutiny” test when government action infringes on fundamental rights: Can the government demonstrate that its action is both necessary to further a “compelling state interest” and “narrowly tailored” through the “least restrictive means” to advance the compelling interest.

In this pandemic, the government does indeed present a compelling state interest to preserve the health, safety, and welfare of its communities. So the constitutional question becomes whether the actions by state and local leaders are narrowly tailored by the least restrictive means. In other words, do these orders result in the least possible infringement on our fundamental rights and liberty while still achieving the government’s purpose of protecting us from COVID-19?

This determination should turn on whether the government’s orders are neutral and objective. Do social distancing and other health safety measures apply equally to all entities regardless of their type? COVID-19 does not distinguish between 10 or more people in a restaurant versus 10 or more people in a church, so neither should government restrictions.

Church is essential, and the free exercise of religion is specifically enumerated in our First Amendment because the founders understood how essential spiritual activity and religious liberty are to people and society. For a state government to take any action that specifically distinguishes churches as “non-essential” is contrary to the First Amendment’s purpose. It’s a dangerous precedent that government could consider itself the arbiter of private essential services.

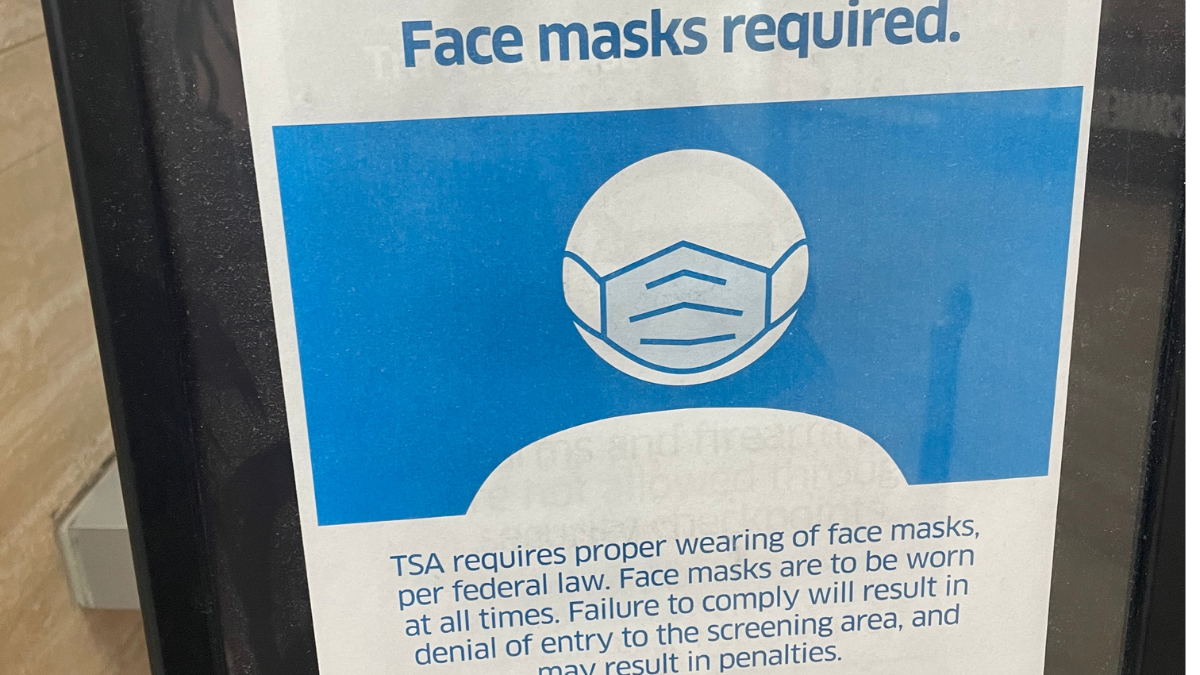

Government’s action to prohibit mass gatherings, including church gatherings, is constitutionally sound for the temporary timeframe that the Wuhan coronavirus provides a compelling state interest rationale for stay-at-home orders. The virus is highly contagious, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommendations are the best-known ways to stop its spread. Because the virus does not distinguish between mass concert gatherings and mass church gatherings, the government can properly issue a neutral order that does not intentionally target religious groups.

Unfortunately for the pastors who have chosen to disregard the order against congregating, this common-sense restriction is constitutionally sound. Even if the state order were not in effect, we should all do the best we can to comply with federal recommendations.

While church is essential, its form and function can change for the temporary health crisis timeframe. A state’s actions would become unconstitutional if it prohibited online church gatherings, as online meetings do not risk spreading the virus, so government action would not advance a compelling state interest.

Where We Are Going

Churches and other private entities need to be wise in understanding the difference between what government can and cannot do in responding to the COVID-19 health safety crisis. When the government oversteps, we must use legal methods, not just mere noncompliance, to challenge those actions.

President Donald Trump has provided leadership, federal support, and agency recommendations to state and local governments, including constitutional deference to the states for their own determinations of these orders. This is federalism in action, and now it’s up to the individual states to properly implement the federal recommendations according to the needs of their specific communities.

As these issues will undoubtedly be litigated long after the pandemic has passed, we should be very grateful for federal originalist judges and Supreme Court justices who continue to preserve the delicate balance between protecting fundamental rights and limiting government power. The more we can appoint to the bench moving forward, the better. We are going to need them.