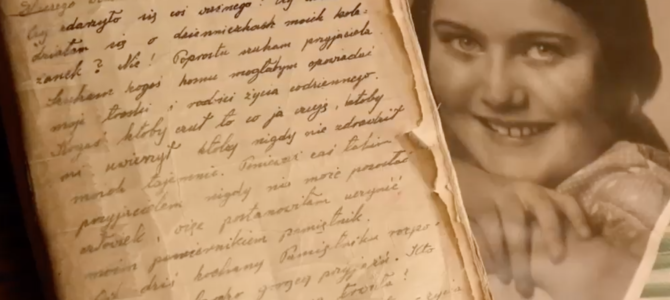

“I just want a friend.” With these words, written on Jan. 31, 1939, 15-year-old Polish Jew Renia Spiegel stated her reason for starting a diary. At the time, she was living with her grandparents in Przemyśl while her mother, Róża, and younger sister, Elizabeth (née Ariana), were in Warsaw promoting Elizabeth’s career as a child actor.

That summer, Róża brought Elizabeth to Przemyśl for vacation and went back to Warsaw. In September, the German and Soviet armies invaded and divided Poland, effectively separating the sisters, who were in the Soviet-occupied part of the country, from their mother, who was in the German-occupied zone.

In the second paragraph of her first diary entry, Renia addresses her new friend: “Today, my dear Diary, is the beginning of our deep friendship. Who knows how long it will last? It might even continue until the end of our lives.”

Her words would prove prophetic. Renia kept the diary until July 25, 1942, when she wrote what would be her final entry: “My dear Diary, my good, beloved friend! We went through such terrible times together and now the worst moment is upon us. I could be afraid now. But the One who didn’t leave us then will help us today too.” Five days later, Renia was shot by the Gestapo.

A Contemporaneous Account of the Holocaust

In the foreword to “Renia’s Diary,” which Penguin Books released on Sept. 19, Holocaust historian Deborah E. Lipstadt observes that within 15 years after the end of the Holocaust, thousands of Holocaust memoirs were published. But she notes that diaries are “fundamentally different from memoirs because they are contemporaneous accounts.”

Whereas the memoir author “knows the end of the story,” the diary author does not. The result is that “what may seem to be of relatively little importance to the diarist may, in fact, turn out to be of great significance. And conversely, what may seem utterly traumatic to the diarist may pale in comparison to what will follow.”

At first glance, much of “Renia’s Diary” seems to consist of that first category of “relatively little importance.” In spite of the deep pain of missing her mother (her father is a distant and rarely mentioned figure), and the increasingly poignant references to the events going on in the world around her that modern readers will understand far better than she, the bulk of the diary consists of the day-to-day trifles of a girl’s life.

Renia worries about doing well in school and being liked. She is alternately insecure (“I’m so different from my friends. … I don’t know how to ‘behave’ around boys”) and confident (“I now have a so-called social life and, to be honest, I’m quite popular”). She can sometimes be downright catty (“Krzyśka doesn’t know anything and speaks as if she has dumplings filled with sand in her mouth. … Dziunka is considered the most boring person in the class and, indeed, she is”). She pines over a boy (“I’m so blue! I’m so low. I’m in love and mocked by the object of my love”).

A Glimpse of Daily Life During the War

While many of Renia’s words are reflective of typical teenage angst, many others are not. As the war drags on, its effect on Renia’s daily life is magnified:

- “There were unexpected nighttime raids. … People were rounded up and sent somewhere deep inside Russia. So many acquaintances of ours were taken away.” (April 24, 1940)

- “I don’t know what’s going to happen to us. … I’m terrified. Almost the whole city is in ruins. A piece of shrapnel fell into our house.” (June 26, 1941)

- “Today I’m like everyone else. … Tomorrow, along with other Jews, I’ll have to start wearing a white armband.” (July 1, 1941)

- “Yesterday I saw Jews being beaten. Some monstrous Ukrainian in a German uniform hit every one he met. He hit and kicked them, and we were helpless, so weak, so incapable. … We had to take it all in silence.” (July 28, 1941)

- “Again a day came when all former worries faded. Ghetto! That word is ringing in our ears, it terrifies, it torments. … Last night everyone was packing, we were ordered to leave our apartments before 2 p.m. with 25 kilograms of possessions.” (Nov. 7, 1941)

Renia’s Poems Range From Themes of Youth to Mortality

Sprinkled throughout the diary are Renia’s original poems. Some of them reflect their author’s youthful emotions and experience. Others reveal the rapidly maturing perspective of a young woman forced to contemplate life, love, and mortality in a world gone mad. On Feb. 5, 1941, Renia writes of her confused feelings for her boyfriend, Zygmund:

Strange thoughts tremble inside

cloudy, half-sleeping, dreary

jumbled into a nightmarish ride

wobbly and clumsy and blurry

spring water comes as if from a gutter

there are red, juicy berries

and this misguided, drunken thought — water

The lips’ effort is a futile flurry

The effort of brain throat cracked dry lips

Words don’t want to sound out

Nobody hears the lamenting apocalypse

Just those entangled thoughts all out

Splashing of water, forest-grown berries

And this unspoken out loud

Word — water — that carries!!!

Lines she wrote on July 16, 1941, are a mix of joy, foreboding, and defiance:

Be merry, friend, and laugh

embrace the passersby

feel good enough to cry,

“I’m living,” that’s enough!

And a strange crowd crept out

From cellars hot and damp

A swarm of pale gaunt faces

eyes shone like a lamp

a starving swarm that faints and sways

crept from the rubble, and see

They all fell into a strange wild craze

and laughed in a hysterical haze

and … felt happy

see the one who sat on a pile of rubble

he has no kids, no wife, no home

he poured the vodka in his mouth

and puked his blood out in wild laughter

he clung to every passerby

and howled, ‘I live, that’s what I’m after!’

From the end of 1941 until her death in July 1942, Renia’s entries are increasingly ominous, expressing her deepening fear and uncertainty about the future. Yet her faith in God is undiminished, and she continues to find both comfort and strength in her blossoming romance with Zygmund and in the certainty of her mother’s love.

Almost every entry in the diary ends with the words, “You will help me, Buluś [her pet name for her mother] and God.” Zygmund, or Zygu, as Renia calls him, encourages her writing. “Zygu says he absolutely must read you, and I don’t want to think about it, because then I’d write dishonestly. … I’d write for him … [and] this diary would not be genuine.”

The Story of Renia Lives On

Renia ultimately does let Zygmund read, and it is Zygmund, in the end, who preserves her diary when she is gone. As the Gestapo began rounding up thousands of Jews, either murdering or moving them to concentration camps, a small fraction received a reprieve in the form of a work permit.

Zygmund received such a permit; Renia, her sister, and grandparents did not. In the afterword to “Renia’s Diary,” Renia’s sister, Elizabeth, writes, “Somehow — I don’t know how, and he never told me — Zygmunt [sic] smuggled Renia and his parents into the attic of a three-story tenement house … where his uncle … lived.”

Zygmund also smuggled Elizabeth out of the ghetto to the home of one of her school friends, who hid her until she could be taken to Warsaw to rejoin her mother. It is not known what became of Renia’s and Elizabeth’s grandparents, but Elizabeth believes they were shot, “too old for the Nazis to want to take them to a camp.”

Somehow Zygmund held on to the diary and escaped the fate of so many of his countrymen. Years after both his parents and Renia were murdered, he tracked down Elizabeth, who had moved to the United States, and presented her with the diary.

Elizabeth, having converted to Christianity and started a new life, couldn’t bear to read it. She locked it in a safe deposit box and focused on the future. It wasn’t until she had children and they began asking questions that she decided it was time to face her past. She still hasn’t read the entire diary but has decided to “let my sister’s words and poems speak for themselves.”

“Renia’s Diary” will not replace Anne Frank’s diary, Elie Wiesel’s “Night,” or Corrie ten Boom’s “The Hiding Place” in the annals of first-person Holocaust accounts. But the honesty of Renia’s voice, her undeniable way with words, and her eyewitness reporting on a time in history that must never be forgotten should be enough to earn “Renia’s Diary” its own place on the shelf.