One hundred and twenty-two years back, on Sept. 12, a small frontier outpost contingent of the British Indian army, of the 36th Sikh Regiment, was overrun in one of the most famous last stands in human history. Twenty-one Sikh soldiers died fighting to the last man, defending a fort from 10,000 rebellious Afghan tribesmen. They died fighting like demons, commented an Australian officer who witnessed the battle.

By the time the battle was over and the fort was overrun, the 21 Sikhs had killed hundreds of Afghans. A gigantic British Indian force finally retook the fort, but that still didn’t stop the United Kingdom’s global policing mission for some time. Afghanistan remained ungovernable. After a while, the British realized that and left it to be ruled by local allied tribesmen implementing their own vision of society, with aerial bombardment from time to time. The British hope of turning Afghanistan into a liberal democracy under the British crown died a dusty death.

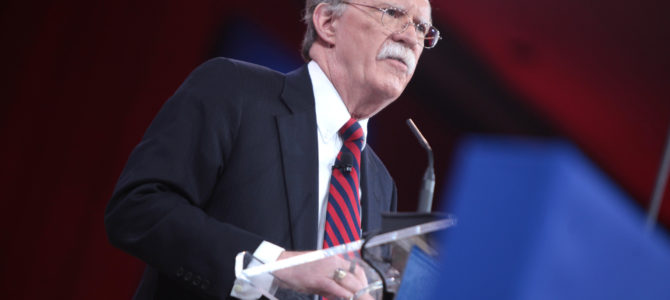

This particular history is important, as President Trump looks for a new national security adviser (NSA), after the departure of John Bolton. People have many different opinions about Bolton. Some people call him a neoconservative, and others say he’s a foreign policy realist. Bolton was neither.

Neoconservatives are essentially liberal interventionists on steroids. They are former Trotskyists who gave up on internationalist Marxism, only to adopt internationalist liberalism as the children of the same Enlightenment ideals. The former ideology is more brutal than the latter, but both retain the same ideals of shaping humanity and the world into one single mold. Every single society can be equal, regardless of culture, history, and geography; all one needs is to try installing either Marxism or liberalism. Bolton never suffered from those delusions, so that’s a credit.

Bolton wasn’t a realist, either. Conservative foreign policy realism understands that regions in the world are shaped by their history. It understands that hegemony is unsustainable in the long run and that a person or military simply cannot spread any foreign idea through force.

Most importantly, realism understands threat prioritization and what we call “relative gains,” to cut losses and compromise in secondary theaters and focus on the bigger threat. The Middle East, by that logic, is a declining threat compared to China.

Bolton never understood compromise, and he never saw any threat that is minor and secondary. I have no interest in judging Bolton, and it is always difficult to judge anyone without being in his or her position. But whatever he was, with his strange mix of sovereigntist militarism and ahistoric threat analysis, he was neither a neoconservative nor a realist.

Understanding History Is Key to Foreign Policy

It is Bolton’s ahistoricism that is emblematic of the foreign policy blob. In my years as a former foreign correspondent, and subsequently a columnist and a foreign policy academic and analyst, the one thing that bothered me most was the lack of historical knowledge in the foreign policy community in both the United Kingdom and the United States.

Some of that is understandable. World history, with all its complications, is not taught well in high schools and universities. A significant crop of junior analysts grew up in post-Cold War triumphalism, with nothing to see, read, or hear about the need of narrow national interest, amoral compromise, and back-channel deals and realism.

This is the End of History generation, whose natural inclination is technocratic, with a dose of military force whenever needed. They are comparable to the British imperial officers in the 1890s — the memories of the last great power war lost in over 70 years of comparative peace, with imperial policing operations in unruly parts of the world.

That brings us back to Afghanistan. The War in Afghanistan was what could be called a Just War in 2002. Theories of war dictate a retributive or punitive campaign, one that could even be carried on with extreme prejudice and brutality, to defeat and deter an enemy from further misadventures. The war against the Taliban for harboring al-Qaeda fell in that category.

However, the nation-building in Afghanistan to the attempt at instituting liberal rights are post-facto justifications of something that shouldn’t even be there in the first place. The Western troops, including the dead British in Helmand and the dead Americans in Kandahar, were not there so a couple of square miles in Kabul has cafes where people regardless of their sex can mingle and read poetry. It is a noble and worthy goal to aspire for liberal democracy in Afghanistan, but it is perhaps not the burden of Western taxpayers, when that same money could be used to donate to private organizations teaching trades and craftsmanship to recovering opioid addicts.

The U.S. Did What It Could in Afghanistan

Here is the harsh truth, which everyone knows but refuses to discuss openly. If the goal of the war was to defeat the Taliban and decimate al-Qaeda, it was over by 2003. If the goal of the war was to ensure Afghanistan would replicate Switzerland, we are in for colonization of a land that was invaded more than a thousand times, but never colonized, and the effort will last centuries until it leads to the eventual collapse of another empire.

Only ahistoric hubris would dictate that America could manage what the ancient Greeks, medieval Persians, and modern British and Soviet empires couldn’t: a “civilizing mission.” Afghanistan, however, can be permanently “pacified,” if not “civilized,” but that would require a level of genocidal brutality that modern military forces post-World War II are not allowed even to ponder.

The only thing, therefore, that we can do in Afghanistan is to keep a wary eye from a distance and let local warlords duke it out. If there are pro-Western warlords who can go toe to toe with the Taliban and in turn pacify huge swaths of the region by any means necessary, they deserve support and weapons. But they don’t need micromanagement, they don’t require American continuous troop presence, and they definitely don’t need any moralizing liberal lectures on how to stick by human rights rules in warfare. In fact, without American presence, the Taliban would be focused on other regional great powers investing in Afghanistan, such as India, Iran, and China, requiring them to carry their own security burden.

Occupying Afghanistan Is a Fool’s Errand

An anecdote often discussed in foreign policy circles is that of the Soviet central committee just immediately before the invasion of Afghanistan in 1979. The military officers present were reticent, with some complaining about trying to stabilize a region that is broadly “semi-feudal” and where the central writ only runs in the capital, Kabul.

The ideologues, fresh from their high-flying days watching America retreat from Vietnam, declared that “there is no land that is not ready for a red flag.” The rest, as they say, is history. Fast-forward 40 years, change Marxism to liberal democracy, and observe a repeat of the same fiasco.

What the British realized after much bloodshed, and the Soviets failed to comprehend — what Trump understands, but the liberal internationalists refuse to — is what conservative foreign policy realists regularly wrote: that there’s no end to occupying Afghanistan, and there’s no benefit in staying forever. Afghanistan won’t be the Netherlands anytime soon, and to try that is futile.

A far better option is to let nature take its course. Research suggests local powers, proxies, and warlords should duke it out, and if anyone is capable of pacifying the Taliban by force, they should offer a hand of alliance and a shower of weapons and cash. Meanwhile, focus on a former Cold War rival returning to form in the Pacific. President Trump’s next NSA, whoever he is, should remember this historical wisdom.