After the fall of the Berlin Wall, the reigning assumption across the West was that we had arrived at “the end of history,” a notion most famously promulgated by Francis Fukuyama’s eponymous 1992 book arguing that liberal democracy and market capitalism had prevailed over rival political and economic systems for all time to come.

The dreams of the immediate post-Cold War era foretold a new global convergence, a world transformed by commerce and technology in which competition and conflict would become relics of an ideological past. In the euphoria of the moment, it became an article of faith that the march of knowledge and material progress carried with them the lasting improvement of human behavior and moral progress.

Even before the ink was dry on such rosy pronouncements, old and ominous disturbances erupted that should have raised questions about this unwarranted optimism. Saddam Hussein had recently attempted to annex Kuwait, Slobodan Milosevic was soon setting about his campaign to “cleanse” Bosnia, and Osama bin Laden had already formed a network of jihadists under the banner of Al Qaeda that would soon declare holy war against all Americans “civilian and military.”

Yet the specter of such atavisms and aggressions was shrugged off. The iron laws of political and economic determinism were bound to assert themselves, we were told, and rising global prosperity would advance the cause of human rights as the world’s tyrants and terrorists were sent packing.

In truth, the continued expansion of the liberal world order did not seem like an entirely mad proposition. As Steven Pinker has ably documented, we are living in perhaps the most peaceable age in our species’ existence, marked by a conspicuous absence of war among great powers. The unprecedented prosperity of this era has lifted hundreds of millions of people out of grinding poverty. And the steady advance of democracy has meant that more nations than not count themselves under the auspices of consensual government. For a time it seemed plausible that, however durable the systems of tyranny, they would eventually be compelled to liberalize politically lest they stagnate economically.

In recent years, however, there can be little doubt that the liberal order has begun to unravel. In the economic realm, China has boomed and (by some measures) surpassed the United States as the largest economy in the world. If authoritarianism hasn’t necessarily meant stagnation, liberalism – afflicted by sluggish and inequitable economic growth across the Western world – hasn’t necessarily meant success.

Meanwhile, the competition for power in international relations has resumed with what Otto von Bismarck succinctly termed “iron and blood.” Revisionist and repressive states dissatisfied with the status quo have paid little heed to the Western injunction that the great game of nations is over. In Asia, Europe and the Middle East, aggressive autocracies – China, Russia and Iran, respectively – assert a civilizational challenge to the current configuration of power and aim to shape a new order more congenial to their interests. So, far from embracing and codifying the American-led arrangement, as the bien-pensant global elite have envisioned, these powers are vying, each in their fashion, to subvert and extinguish it.

A Distinctly Unnatural Rise

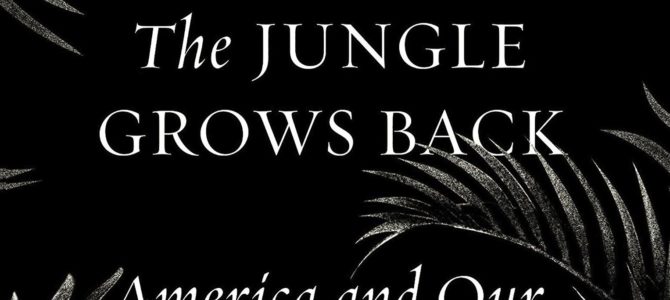

In a timely and trenchant new book, Robert Kagan argues that the progressive conceit about the inevitable triumph of the liberal ideal was always nonsense. In The Jungle Grows Back: America and Our Imperiled World, Kagan explains that democratic capitalism is not remotely the world’s default system of political economy. A distinguished historian and senior fellow at the Brookings Institution, Kagan also dissents from the prevailing view that war has become (in Pinker’s words) “all but obsolete.”

Kagan’s tightly argued brief offers a sorely needed reeducation about the strategic and moral realities of power in an imperfect world. Against the chic theories of “permanent peace,” Kagan takes the bleaker perspective of the ancient Greek philosophers Heraclitus and Plato that war is the “father of all,” while peace is a mere parenthesis in human affairs.

On this view the source of progress in the postwar era is not the natural culmination of historical forces, but instead the distinctly unnatural rise to preeminence of the United States, and its choice to be actively engaged in the world. At a time of rising authoritarian nationalism across the West, what gives The Jungle Grows Back its special value is Kagan’s cogent explication of the heyday of American internationalism.

After the Second World War, U.S. officials reluctantly arrived at the conclusion that it fell to their nation – as much for its own sake as for the world’s – to construct a more durable international system than the one that had collapsed in the late 1930s. Blessed with advantageous geography (its relative isolation makes it less vulnerable to attack and less threatening to others), unparalleled economic and military might, not to mention a national ideology based on Enlightenment principles, the United States was uniquely positioned to take up the mantle of global leadership.

Still, the question lingered: would Americans accept this onerous duty that history had thrust upon them? There was, as Kagan painstakingly reminds us, nothing preordained about their decision. After World War I, the United States had balked at such a burdensome role when it rejected both the League of Nations and participation in the Versailles settlement. At the time, of course, the British fleet ruled the waves, underwriting a relatively open world order that made America’s continued rise a fait accompli.

By contrast, after World War II the British Empire was bloodied and bankrupt, and America would have to look after its interests without the benefit of British power. The best thinking in Washington held that the United States, at great expense in blood and treasure, would be required to stand sentry on distant frontiers and on the high seas – not to defend its narrow interests alone but to arrest the cycle of multipolar conflict that had culminated in two world wars.

This could only be achieved by means of protracted security guarantees and a permanent “onshore” military presence in critical regions. President Truman, acutely aware of the daunting implications of that task, can be forgiven for considering it “the most terrible responsibility that any nation ever faced.”

In discharging that responsibility, the architects of Pax Americana transcended national interest as traditionally conceived, which was limited to “defense of the state’s immediate and physical and economic security.” Sometimes miscast as a simple reaction to the Soviet drive for domination, this new strategy of order-building emanated from a reading of the recent past, not of the coming future.

If Americans and their way of life could not be safe in a world ruled by hostile autocratic powers – a manifest lesson of the rise of Nazi hegemony – it would not suffice for the United States to sit “in the parlor with a loaded shotgun, waiting,” as Secretary of State Dean Acheson poignantly remarked. Since the great powers of Europe and Asia could not be counted on to keep the peace, the notables of this era believed, America was compelled to venture into the world without an exit strategy, using its power to establish and sustain a liberal order conducive to its interests as well as its ideals.

‘The Locomotive at the Head of Mankind’

For all the casual talk of American exceptionalism, Kagan contends, it was this “novel definition” of the raison d’état that truly set America apart and put history on a different course. With its unprecedented power and might, the United States assumed a constant forward posture in regions of vital strategic interest to deter and defeat threats to its own hearth and home, but also to create “an environment of freedom” far beyond its borders.

The assertion that the United States has upheld certain norms of international behavior and promoted democratic reform where possible will cause some jaws to drop, and with especially good reason in parts of Latin America and the Middle East where U.S. policy has often turned on a crude form of transactional geopolitics.

It’s fair to say there has been no great effort, as Henry Luce predicted in his famous essay “The American Century,” to impose democratic institutions on the good shepherds of Tibet. Worse still, American dollars have frequently been dispatched abroad to shore up the rule of obliging authoritarian strongmen. But it remains a simple fact that the United States has also frequently employed a range of methods, from moral suasion and economic pressure to direct military force, to entrench democratic government and prevent military coups among friend and foe alike.

Whatever the blemishes on this order (and there were and will remain many), in the last analysis the United States and its allies have made swathes of the world safe for democracy, built an open economic system that integrated diverse nations in a web of free-market and free-trade agreements, and fostered a revolution in international security by suppressing renascent geopolitical struggle.

The passage of time has made the sheer magnitude of this achievement simultaneously hard to fathom and easy to take for granted. Paeans to a great “rules-based” order notwithstanding, its most perceptive defenders and detractors have recognized that its enduring success has owed to America’s military strength, and would not survive long without it. This fact is what has made the United States, to borrow again from Acheson, “the locomotive at the head of mankind,” and the rest of the world “the caboose.”

Those enlightened statesmen “present at the creation” of the postwar order, like the founders of the American republic, subscribed to the principles of natural right that they held to be universal and irrefutable. However, also like the American founders, they were not utopians about the means required to secure them. A clear-eyed view of the human condition, as well as the harsh wages of experience, had taught them otherwise.

The downward spiral of the interwar years bred no confidence among these “wise men” that “splendid isolation” or “offshore balancing” was anything other than a lethal ruse in an interdependent world. It was now supremely, even mundanely, apparent that Americans’ own well-being depended on the well-being of others. Hence this cohort believed that although the world was a fundamentally anarchic place, it could be kept at bay – and for the benefit of what Alexis de Tocqueville called “self-interest rightly understood,” needed to be – through confident American leadership.

Worrying Portents

It is hard to overstate how out of fashion such tragic insight is nowadays. Some dismiss fondness for these old verities as nothing more than “teary-eyed nostalgia.” There is a widespread conviction that increasing global interdependence is proof that the long arc of history bends toward justice. A consensus of discrepant elements has therefore arisen that no longer judges America’s activist global role to be necessary or even defensible.

These are worrying portents, since the world America made (as Kagan notes in his previous book of that title) is in grave danger from a host of adversaries. Russia has moved to re-establish its sphere of influence by dismembering Ukraine, intervening in Syria, and brazenly interfering in the elections of Europe and the United States. China, the great rising power of the century, has consolidated its authoritarian political system while employing coercive measures to expand its control of the South China Sea. Iran seeks to entrench its theocratic influence from Persia to the Mediterranean and beyond.

These nations do not have much in common, but what they share is crucial: an autocratic form of government at odds with the prevailing global structure of liberal hegemony, as well as a belief that power is necessary for their survival in such a world. They are correct in perceiving the precariousness of their despotic realms, which are anathema to the core elements of the liberal order. So long as these regimes remain authoritarian bastions, they will naturally seek to obstruct and overthrow that order, beginning with a new arrangement of power in the Baltic republics, the Taiwan Strait, and the Golan Heights.

But a still greater worry for this global order lies with American staying power, not least under the command of an erratic, evasive, unpredictable and unprincipled president. President Trump’s stark “America First” impulses have confirmed and accelerated the trend among Americans toward a more normal and much narrower conception of the national interest that may not involve – as the president himself has speculated publicly – the defense of a NATO-ally like Montenegro. Naturally, it has begun to sew doubts among foreign partners that America is no longer the benign hegemon they once knew (if rarely acknowledged).

This turn away from America’s deep international engagement began, as Kagan recounts, with Trump’s predecessor who spoke incessantly about “nation-building at home” in lieu of being the world’s policeman. This sauve qui peut approach corresponded with President Obama’s belief that America could or should no longer bear the moral and material costs of global leadership. Pronouncements by the Obama administration that “there is no military solution” to hellish conflicts in far-flung lands replaced old axioms about peace through strength and the responsibilities of great power.

The Obama administration’s chilly indifference to the scheme of American hegemony has been replaced by Trump’s burning hostility to it. Whereas Obama’s measured retreat from the world arose from a misguided search for a balance of power, Trump seems determined to retreat in order to hoard America’s power while transforming the global order into a tribute system. (Witness the belligerence toward U.S. allies on trade and security issues paired with efforts at greater cooperation with U.S. adversaries.) This amateurish and blustering approach runs afoul the American interest as much as Obama’s amateurish and feeble approach. Call it “bullying from behind.”

Illiberalism from Budapest to Beijing

There is little sign that the United States is preparing a course correction. Kagan calls attention to the disturbing fact that of the four major political figures on the national stage in 2016 – Obama, Trump, Bernie Sanders, and Hillary Clinton – only one sought to uphold America’s role as the “indispensable nation” in world affairs. (Here one must interject that even Clinton’s position was badly compromised, refusing as she did to defend her signature accomplishment as secretary of state, namely the Trans-Pacific Partnership trade agreement.)

The profound skepticism, if not scorn, for a forward-leaning foreign policy did not derive from the current administration and, it is safe to presume, will not disappear with it. Taken to its logical conclusion, it is a formula to transform the United States into an unexceptional and ephemeral superpower.

It is a characteristic error of the times in which we live to imagine that geopolitical order can exist without American primacy. It may seem remarkable to our postmodern sensibilities, but “the creation of the liberal order,” writes Kagan, “has been an act of defiance against both history and human nature.” Judged from the historical perspective, nation-states founded on law and liberty have been an aberration. Most political communities throughout the ages have been forged not (to use the terms of the Federalist Papers) on “reflection and choice” but by “accident and force.”

The obituary of history, then, has been written prematurely. Even in a world guided by a liberal hegemon, it is exceedingly difficult for cosmopolitan ideals to triumph over the eternal stirrings of family, tribe, and nation that help account for the recrudescence of illiberalism from Budapest to Beijing. The palpable longing for a demagogue and a strongman to assure order resonates more in the human breast than we like to think. “It is ultimately a cruel misunderstanding of youth to believe it will find its heart’s desire in freedom,” says Leo Naphta, the protagonist of Thomas Mann’s The Magic Mountain. “Its deepest desire is to obey.”

Despite its actual and potential disorder, the world is still recognizably that which the postwar settlement bequeathed us. To preserve it will require the moral, material, and martial resources that first brought it into being. Not so long ago Reinhold Niebuhr, seeking to summon Americans to their better angels in a fallen world, argued that what he called “the world problem” could not be solved if America did not “accept its full share of responsibility in solving it.” The world has changed dramatically since then, but the world problem has not.

The only question is whether Americans have the wisdom and will to continue in their grim and grand vocation, serving – as Plutarch said of the Romans – as an anchor to the floating world. In all the years since America first dropped its anchor, the answer has never been in greater doubt.