On just about every legal and policy front, Americans are slowly realizing that many key state and local institutions have become merely outposts for a federal government controlled by special interests. This strips us of the self-government that is our birthright as American citizens, because it takes from us the power to determine the rules and structures that determine how we’re allowed to live.

For example, as federal spending has exploded over the past century, it has colonized the so-called “charity” sector. One-third of all money nonprofit organizations consume each year comes from the federal government, and more from state and local governments. This corrupts these organizations into special interests, giving them strong incentives to lobby for increased federal control of Americans’ earnings so they can siphon off even more to themselves. They frequently do this not only by direct political action but by releasing reports and creating initiatives that appear third-party, impartial, and community-driven, but are really simply political activism disguised.

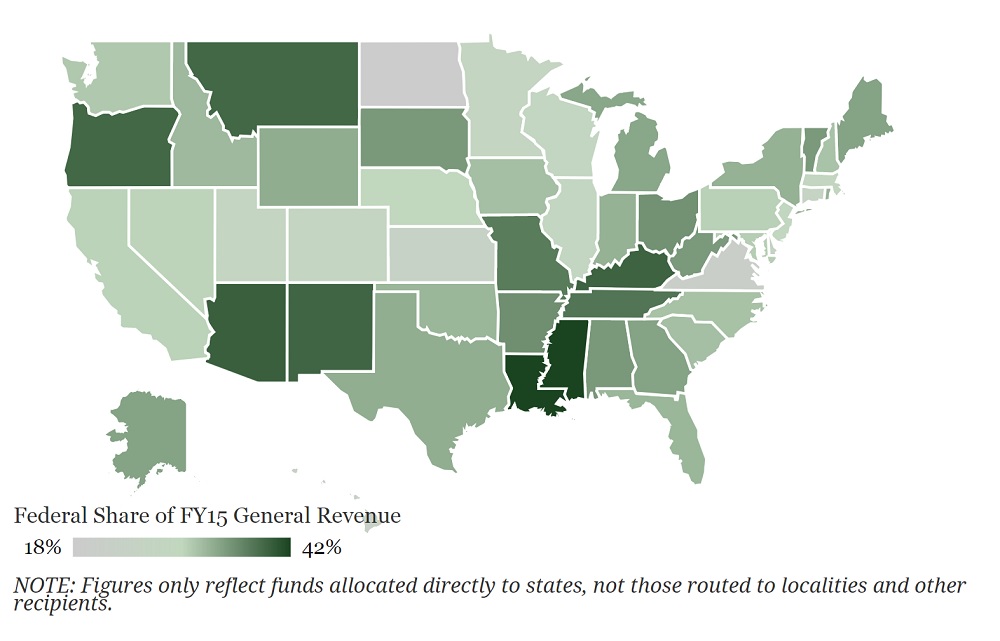

Federal spending has similarly colonized state and local governments. On average, federal funding supplies approximately one-third of state budgets, and approximately one-quarter of local budgets. A 2017 Governing magazine chart shows below which states are most and least reliant on federal spending. State agencies, many if not most of which receive significant federal funding, also create reports, initiatives, and programs that push for expanded government, both at the state and federal level. In other words, it has become routine to use public dollars and institutions to lobby against the American public’s pocketbooks and self-determination.

While the federal government technically supplies less than the majority of most state, local, and nonprofit entities’ budgets, this money easily provides enough leverage to direct the rest, as demonstrated in a recent book by Emmett McGroarty, Jane Robbins, and Erin Tuttle (with whom I’ve worked on research and writing projects, but not this one). “Deconstructing the Administrative State” details just how far the federal government has absorbed formerly local entities, erasing Americans’ ability to control or even influence local politics and public initiatives.

This hidden dynamic reveals why local school boards and city councils, for example, feel free to ignore people who storm their meetings demanding change, despite the illusion that they are local bodies of governance. So do local zoning and urban planning groups, transportation commissions, police, land management boards, environmental stewardship organizations, charities, community organizations, and more. Different city, same kind of “downtown revitalization” plan that sends tax money after big developers who happen to be campaign donors while the local media outlets cheer instead of publishing the ugly financial risk assessment.

Many public and private American institutions now typically behave like a social version of big-box chain stores: same entity, different location. Maybe the aisles run side to side instead of front to back, but largely everything is the same.

Strategies For Filching Power from Individuals Like You

“Deconstructing” gives the following list of ways the federal government extends its control through myriad so-called local institutions:

- Creating schemes to work around the constitutional structure, such as cooperative-federalism programs, “ghost governments,” and independent commissions;

- Distributing federal grants, sometimes directly to state subsidiaries rather than to state governments;

- Creating public-public and public-private partnerships;

- Reshaping the American mind by replacing traditional education with progressive education, including control over pedagogy, standards, curricula, and teacher training;

- Generating vast quantities of “research” to justify federal policies;

- Expanding the definition of “public health” to justify federal policies;

- Aligning the economic interests of powerful private organizations to the imposition of federal policies;

- In some states, simply removing millions of acres of land from state and private control.

The big picture of it all is simply corruption: social corruption, political corruption, and moral corruption. Networking American society through these channels inevitably aligns all back to unelected bureaucrats who wield great power and answer largely to themselves. Of course, as the American founders knew and deliberately structured American government against, when people are not accountable to those they are supposed to serve, they’re more likely to abuse power. They use their power to benefit themselves, both directly in growing their power and indirectly in doing favors to friends who are therefore socially bound to reciprocate.

One example of this the book gives is of a key government-commissioned report that helped define federal health agencies’ mission as just about everything under the sun: “all aspects of society, including the built environment, social conditions, and economic opportunity, are determinants of health and thus within the scope of ‘public health.’ In other words, every aspect of human existence lay within the scope of public health and therefore would be fair game for government meddling” (emphasis original).

It’s all very lucrative for the bureaucrats who get to define their purview as almost everything society does, but this arrangement degrades Americans by depriving us of the right upon which our progenitors declared revolution: “No taxation without representation.” American government doesn’t exist to provide oversight of everyone by the few at the expense of the many. It exists to secure our natural rights, chief among which are to life, liberty, and property. It derives its legitimacy solely from the consent of the governed.

If we are governed without our consent — as is the case when we are governed by bureaucracy, since we can’t elect those rulers — genuinely American government is no more. It will have been replaced by tyranny: government that exists for those who govern, rather than to preserve the rights of we, the people. Our government will then have devolved from self-government to exploitation, from every man his own king to a neo-feudal system of kings, vassals, and serfs.

Call It Whatever You Like: It’s Corruption

A number of other books and authors have described America’s neo-feudalism. Social scientist Charles Murray is almost certainly the most prominent. His “By the People” described the entrenched petty — and not so petty — corruption that has by now become the hallmark of American life. Four years ago, I called this phenomenon “mafia government”:

That’s a system of patronage in which the amount of leverage you have depends on your wealth and Rolodex…

At the heart of every mafia enterprise is a racketeering operation, in which businesses and private citizens are forced to pay the mafia to protect themselves from harm. Potential harm includes both what The Mob inflicts and that from outside sources, such as gangs or swindlers. Often, a protection racket arises in areas where the rule of law is weak, because in those areas the police and judiciary cannot or will not provide the protection from criminals everyone needs.

Call it feudalism, neo-feudalism, mafia government, the ruling class, whatever you like: these are all corrupt systems in which citizens lack the power to run their own lives and are subject to rules created by people they can’t affect. This web of helplessness is a direct result of the kind of government McGroarty, Robbins, and Tuttle describe. Polls found that this feeling of voicelessness was a key determinant for voting Donald Trump in 2016.

The authors chronicle the history of how it slowly happened, including structural changes in government such as direct election of U.S. senators and judicial decisions that allowed the federal government to bribe states into its preferred policies. They also give case studies in varied policy areas, including education, infrastructure, health, law, and land. What unites them is their mode of governance. It is the alternative to the American system of constitutional government.

The two have been at war since America’s founding, and so far the corrupt, totalizing system known as progressive government has the upper hand. After all, the United States is the world’s second-largest social welfare state, behind only France.

Helpfully, the trio of authors give very specific recommendations about what Congress, the Supreme Court, and state governments can and should do to address their longstanding transgressions against Americans’ right to government ruled by our consent. They include overturning Chevron deference, passing the REINS Act, returning state functions like health, education, and welfare, and prohibiting federal agency grants to local government.

These are huge political lifts that are unlikely to occur soon. But they are worthy targets for actual American representatives to aim for. This book gives some key reasons why, and shows how.