Spoilers below.

I loved “S-Town.” I hated “S-Town.”

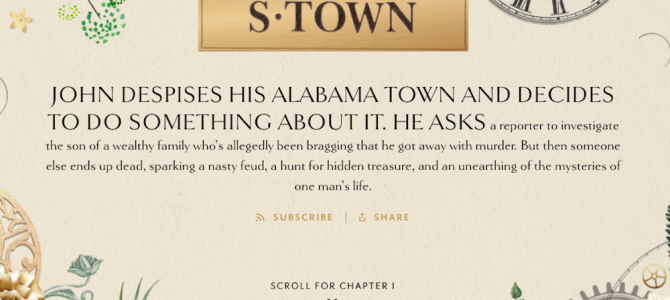

The beautifully crafted podcast by the creative forces behind “Serial” and “This American Life,” which tells the story of a man who can’t bring himself to escape a southern town he hates so much, feels dirty to listen to. Surely the life and death of show’s anti-hero, John B. McLemore, and his family’s fight over the treasure he may have left behind — buried in some corner of his expansive property — is not something 1.5 million people should know about in vivid detail.

After his death, an old flame speaks out about John’s sex life, a friend shares details about his addiction with self-harm and alcohol. And the darker the podcast got, the more I craved.

Altogether, it’s a beautiful masterpiece that tells the story of one man’s pain and why his personal anguish and self-loathing is emblematic of a larger problem. The corruption, poverty, and addiction that plague Woodstock, Alabama are a microcosm of larger societal ills that plague many towns in many states across this country. John’s story becomes an allegory for The Forgotten Man — left to die of despair in the town where he was born and has grown to loathe.

Since the podcast was released late March, many have criticized the show for revealing too much about John’s life. In an interview with Pacific Standard, “S-Town” narrator and creative force Brian Reed explains why he doesn’t think he did anything unethical.

I don’t believe that when a reporter is doing a story about someone who has died, that they can only include elements that the person consented to when they were alive. I don’t believe that’s an ethical problem, and there’s a whole world of journalism about people who have passed away. The whole enterprise of that journalism is to learn more about [those people] than we understand from when they were alive.

[…]

It’s important to be sensitive, and it’s important to always be evaluating what we’re doing, I completely agree with that, and I think that people can disagree with the decisions that reporters make, for sure. But we’re very careful and thoughtful in what we included and what we didn’t — and there’s a lot we didn’t.

Reed has a point — if we only said nice things about dead people, our history books would be little more than propaganda. But John isn’t a political or cultural icon whose life is necessary to prod and scrutinize to get a better picture of our society’s past. He’s a private citizen, and by all accounts, was mentally impaired or disturbed to some degree.

In the later episodes of “S-Town,” Reed reveals that John’s habit of fire-gilding probably gave him mercury poisoning, which usually drives people to madness or suicide. Reed speculates that aspects of John’s personality, like his obsession with societal ills and climate change, paired with anxiety, depression, and thoughts of self-harm or suicide, are common symptoms of being exposed to mercury.

So is it fair to reveal very intimate details of John’s life that he disclosed when he was probably not in his right mind? It seems some details are not necessary to the overall story arc of the show. Repeating rumors of John’s same-sex attraction, digging up an alleged ex-boyfriend, and delving into John’s (almost sexual) fixation with self-harm are not details listeners need to understand why John dubbed his town “Shit Town” and why he decided to stay in a place he hated so much. It seems several of these behaviors also contributed to the mental illness that eventually drove John to take his own life.

After his suicide, Reed contacts some of John’s longtime friends. One in particular emphatically insists that John loved Woodstock and was involved in the town’s founding decades ago. Griping about “Shit Town” was a trait John acquired later in life, he says, along with a slew of new habits — like drinking, tattoos, and self-flagellation, to name a few.

These interests, which we eventually learn are more recent behaviors, seem to indicate John was suffering from sort of mental collapse in the final years of his life. But then again, we don’t know that for sure. John’s body isn’t exhumed and examined for mercury poisoning, nor is his property tested for mercury. He was never psychologically evaluated when alive, though we are told he had grappled with depression throughout his life and took psychiatric medication for a brief period to alleviate it.

So how much of John’s pain and anguish is okay to splay out for public consumption? How many of these sad rabbit trails are really necessary for advancing a narrative of a man frustrated with addiction, racism, homophobia, and poverty in his southern town? Do we need to know about John’s sexual dalliances and frustrations in order to empathize and understand the person he represents — The Forgotten Man?

Reed’s justification for revealing many of these details is thin at best. As I mentioned earlier, our narrator digs up some mercury poisoning experts in one of the final episodes to speculate about the true cause of John’s death. We aren’t given an answer one way or the other, because there’s not enough information to do so. And that’s the problem with the show — there are no real answers or definitive statements about John’s suicide or many aspects of his life. Former alleged lovers are dug up and questioned, but John isn’t alive to refute or respond to their claims or the statements others make about his sexuality. It’s all hearsay, and some of it that family, loved ones, or John himself might consider scandalous and shameful.

We are told these details are important to understand the story — because journalism! — but at the show’s conclusion, this rationale wears thin. In the final minutes of the show, we’re given an almost biblical account of John’s lineage, how his ancestors are tied to the town’s history, and why these familial links bound him to his home in Woodstock, Alabama, for better — and ultimately for worse. In spite of all the things he hated about his town, and all the larger problems with our society his town represents, John never left, because he couldn’t.