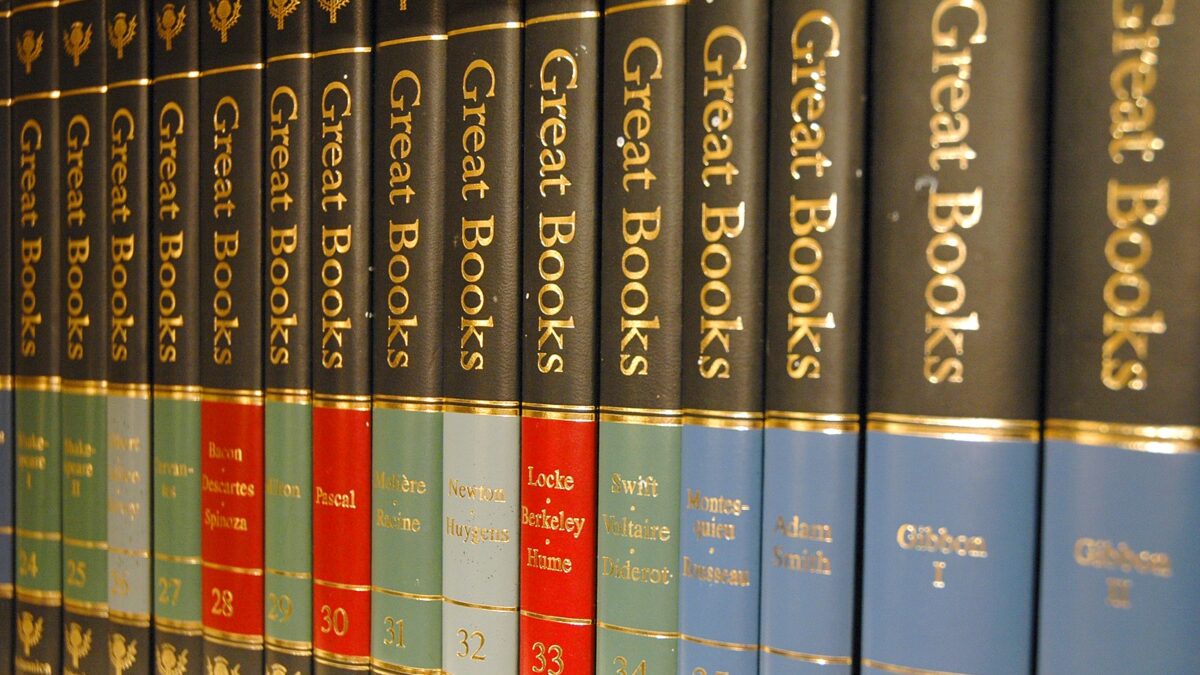

Classical literature has always been a part of the high school experience. Novels such as To Kill a Mockingbird and Pride and Prejudice have become quintessential features of our curricula, the subjects of countless book reports and study sessions.

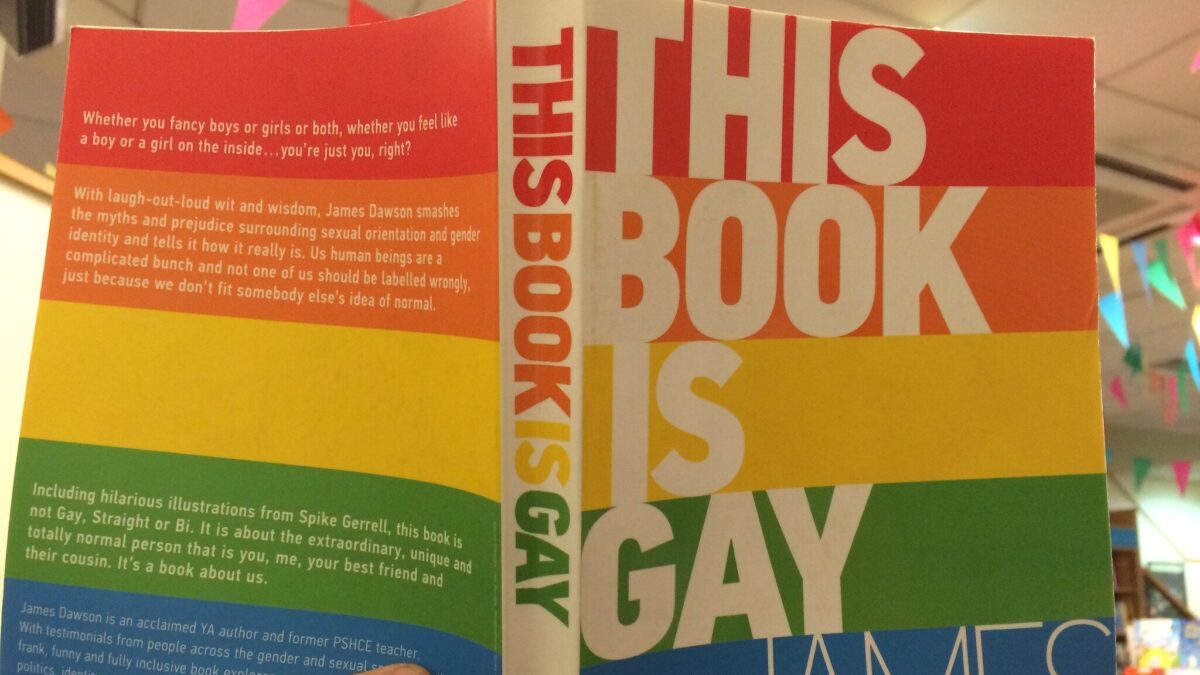

But Shayna Murphy of the Bookbub Blog wants to change that: many books in the classical canon are outdated for today’s students, she argues: “Just because a book is a classic, doesn’t mean it’s necessarily the right fit for a modern-day classroom.” She offers a list of 12 contemporary novels that are, according to her, worthy replacements for our antiquated list of historical reads.

Murphy’s statement—that “just because a book is a classic, doesn’t mean it’s … the right fit”—carries a few assumptions about the nature of the modern-day classroom, and what it is meant to achieve. Do we meet students where they are at, and cater learning to their predispositions and proclivities? Or do we seek to stretch our students, urging them to move beyond what’s comfortable?

Classic Books Cultivate Empathy and Imagination

Many of the books on Murphy’s list reinforce narratives adolescents already want to hear: they are, as she puts it, “relatable.” They meet young adults where they are at, assuaging their fears and coddling their sensitivities.

But one of the greatest gifts of classical literature is that it gives us a glimpse into other worlds—worlds so foreign and different from our own that we are forced to reconsider our assumptions about reality and the self. Beowulf, for instance, offers us a glimpse into an ancient world in which an entirely different set of virtues reigned supreme: in which martial honor and glory were the telos of human existence. The Red Badge of Courage reflects on the horrors of war, opening the eyes of the young reader to a world they will likely (hopefully) never have to experience themselves.

John Green’s explorations of adolescent emotion and existentialism don’t compare to the explorations of virtue and vice, addiction and despair, community and unrequited love in volumes such as The Great Gatsby, The Scarlet Letter, and The Tale of Two Cities.

Novels such as these deepen our empathy, our ability to understand that there is a whole world of experiences beyond our own. Fiction is supposed to develop our imaginations, offering us scenarios, characters, and contexts we’d never otherwise understand. No students need that more than today’s high schoolers.

But that doesn’t mean students will naturally, immediately like the classical novels that teachers give them. Just because fruit and vegetables are good for you, doesn’t mean you want to eat them—they may not be the “right fit” for your lifestyle (especially if you prefer to eat Five Guys and Chipotle every night). Liking healthy food requires the development of taste: the more you eat it, the more you grow to enjoy it.

Similarly, not every student (not even most students) will like their first “taste” of Beowulf or Charles Dickens’s verbose writing style. But the more they’re immersed in these books, the more they develop literary disciplines and patience, and the more they’ll come to appreciate them (even if they don’t particularly “like” a specific author).

Classic Books Deepen Our Knowledge of History

I don’t want to sound too harsh—Murphy’s 12 book alternatives may not be classics, but they’re also not vampire novels or Gossip Girl chronicles. They’re still, for the most part, worth reading. It’s true that The Kite Runner and Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close (two of Murphy’s preferred book choices) could teach students similar lessons about empathy. A lot of students in high school could benefit from books such as these—they’re well-written books, imaginative and interesting.

The problem is that they cannot and should not replace classical works—not just because these works are magnificent in a literary sense, but also because they proffer indispensable history lessons.

One of the biggest problems with Murphy’s underlying premise is not just the idea that the classical canon doesn’t matter—it is the underlying premise that history doesn’t matter. Her suggested reads for the “modern-day classroom” were published in the last couple of decades. With the exception of The Book Thief and Code Talker, which are both set during World War II, none of the books have a historical setting.

So riding on a whaling ship during nineteenth-century America, traversing the perils of the Civil War South, experiencing the horrors of the French Revolution, reveling in the glamour of New York City’s Jazz Age: these experiences are dismissed for their foreign-ness, for their outdatedness. In this dismissal, young adults lose an opportunity not only to expand their mental maps and imaginations—they also lose out on the chance to deepen their understanding of world history.

Textbooks don’t achieve the same effect, as useful as they can be. The student who sits down with a dry, fact-filled summary of the French Revolution will not be as inspired or shocked by its events as he will if he reads about Charles Darnay and Sydney Carton in Dickens’s A Tale of Two Cities. It’s one thing to read a textbook about the Civil War, and another to see it all unfolding through the eyes of a young and inexperienced soldier, like we do in The Red Badge of Courage.

This is the beauty of fiction: it makes us thirst for facts and understanding that we might never otherwise realize we wanted, or needed. It connects us to the fabric of a history that stretches out long before we were born, giving us context for our concerns and cares. But Murphy discards these reads, because today’s students need to read stuff that’s “relatable.”

Classic Books Belong in Today’s Classrooms

A University of Arkansas study recently found that we suffer from an “absence of a coherent, progressively challenging literature curriculum in the secondary grades.” According to a 2009 report by Renaissance Learning, “ten of the top 16 most frequently read books by grades 9-12 students in the top 10 percent of reading achievement … were contemporary young adult fantasies—almost all with middle school reading levels.”

The percentage of American adults who read literature is at a three-decade low, according to a new study from the National Endowment for the Arts. In 2015, only 43 percent of Americans reported picking up a work of literature (novel, play, short story, or poem) in the last 12 months—the lowest percentage since the National Endowment began their survey.

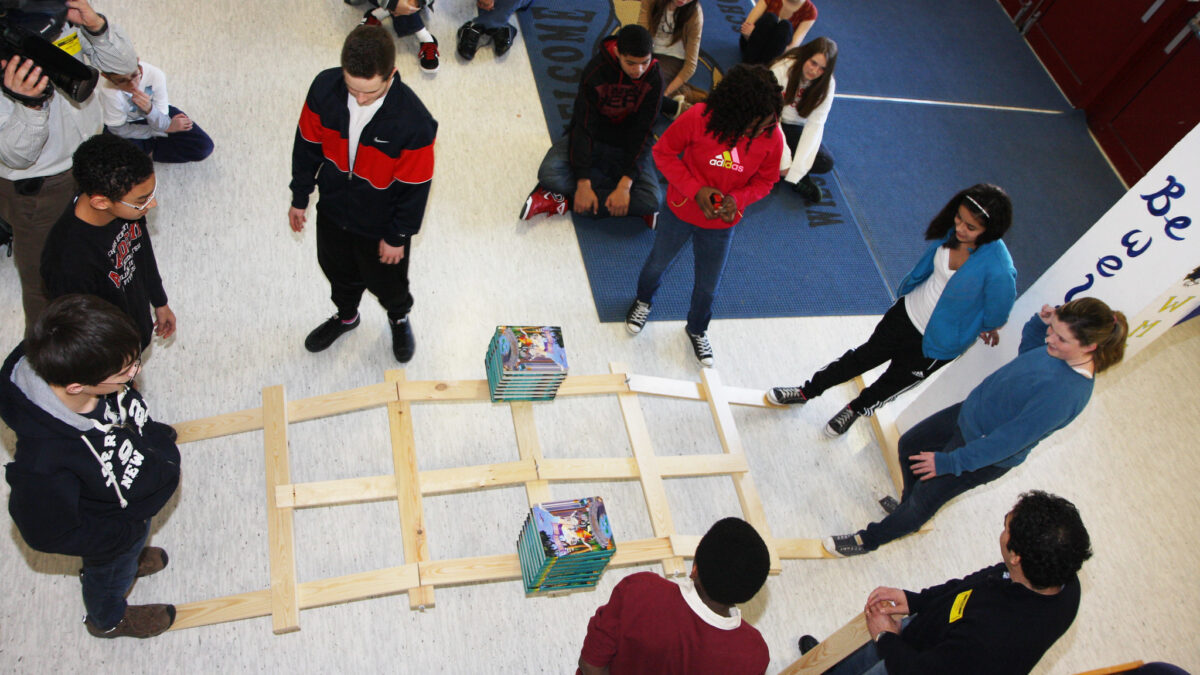

But book-loving seeds are sown far before adulthood: they start in high school, in grade school, even in kindergarten. They start as soon as adults begin putting books in our hands.

It’s easy to just give high schoolers what they want—to let them read “whatever,” as long as they are reading. But the more we encourage them to read classic books, the greater their opportunity to tap into a wealth of historical, classical knowledge that never runs dry. They’ll be encouraged to appreciate not just the temporal diversions of a John Green novel, but to consider the gravity of moments and lives beyond their own experience.

That is just what the “modern-day classroom” needs.