It’s not 1968 yet. It’s not even 1993.

It’s fashionable to freak out about everything. So much of the discussion in the media over the last week has been conducted with a tone and focus that suggests violent crime — gun crimes, in particular — are at historic highs and society is on the cusp of unraveling into mass violence.

There are plenty of ominous signs about cohesion, but we’re not exactly in a civil war just yet. While long-term trends don’t alleviate individual injustices or mitigate the grief and anger we experience about what’s going on, context matters. It matters mostly because discussing these events without placing them in some historical framework creates the type of hysteria that leads to false perceptions and then counterproductive policy.

how did we get here? people shooting each other on the streets of America.. #tragic

— Greta Van Susteren (@greta) July 8, 2016

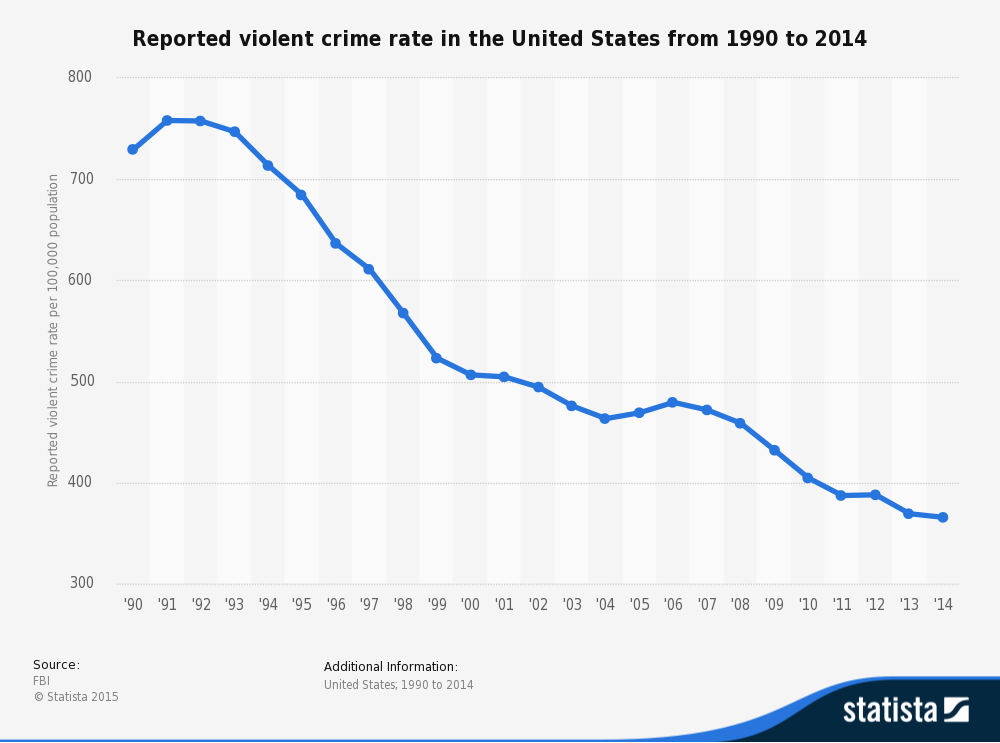

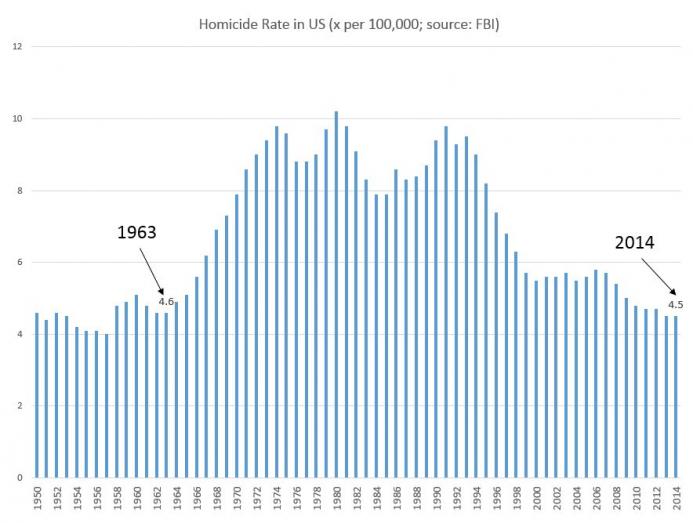

I realize there’s a lot of parsing to do with data, but a broader look at the numbers tells us we’re not only living in an age that’s seen a big drop in violence but perhaps the least violent age in American history. The year Greta Van Susteren first made her name on CNN offering legal expertise on the O.J. Simpson trial, violent crime rates had peaked in the United States. For the next 20 years, they would precipitously fall on every level —including murder, rape, and aggravated assault. People have always been shooting — punching, stabbing, kicking — each other. They just do a lot less of it today.

Homicide rates, for example, have been falling to the point where in 2014 — the last year of FBI data offered — it was at 4.5 per 100,000 people, which is the lowest rate recorded since 1963, when it was at 4.6 per 100,000 people. We know there was a slight uptick in violent crime in 2015, probably making it the second lowest year for homicides in the past 50.

Put it this way: In 1990, in New York City there were 2,245 homicides. In 2015, there were 355. In 1992, Los Angeles County had a record high of 2,589 homicides. There were 655 over the last 12 months. In 1992, Chicago saw 943 murders, or a rate of 34 murders per 100,000 citizens. Although it still owns a far higher murder rate than most major cities, in 2014 there were 432 murders and in 2015 488. Last year, Dallas saw a spike in murders, yet the 10.7 homicides per 100,000 residents was the city’s fourth-lowest total since police started keeping track in 1930. In Denver 95 people were murdered in 1992, 34 in 2014, and 50 (a nine-year high) in 2015.

Stats from almost every city tell the same tale.

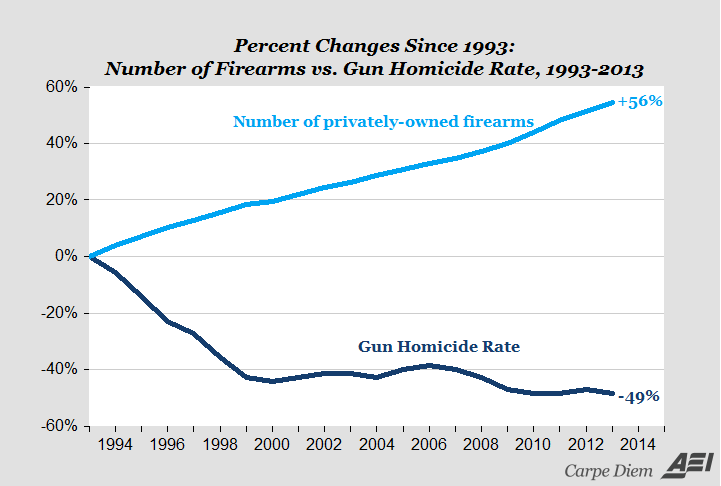

After the Dallas shooting of five officers, President Obama, as he always does, talked about more gun control. “We must take a hard look at the ease with which wrongdoers can get their hands on deadly weapons and the frequency with which they use them,” Attorney General Loretta Lynch insisted. So it’s worth mentioning that this drop in violence has coincided with a spike in the number of guns Americans have purchased. We are told that the availability of guns (not the amount of people who buy them, but the guns themselves) is the problem because they are bought in places with relaxed laws and sold to criminals and terrorists in places with stricter gun control laws.

Despite this reality, according to a 2013 Pew poll, 56 percent of Americans believe gun crimes have risen compared to 20 years ago. This even though overall gun death rates have declined — and let’s include homicides and suicides (most gun deaths are suicide) — by 31 percent over that period.

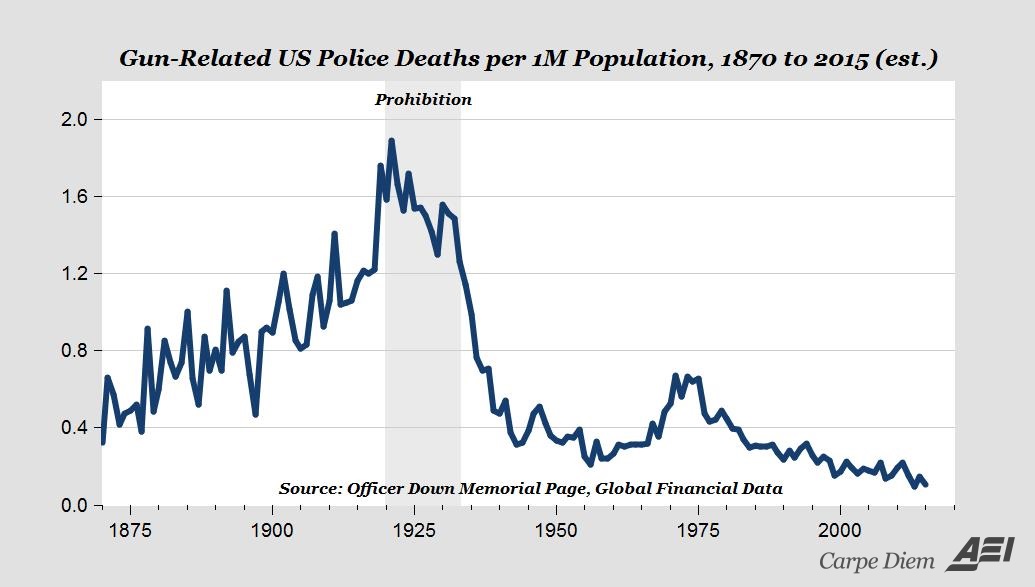

We believe a lot of things that aren’t true. In a 2015 Rasmussen poll, 58 percent of Americans said they believed there was a “war on police.” The murder of five officers in Dallas last week was the worst attack on law enforcement since 9/11. It is in no way to diminish the impact of this event or the lives lost that day to say that the overall trend shows police are not in more danger today than they were 20 years ago. The violence aimed at police has generally followed all other trendlines of violence, which is to say it has decreased.

The recent deaths of a number of African Americans at cops’ hands is also highly troubling, but the debate about it is imbued with a number of societal issues that go beyond mere stats. It’s also far more complicated than conventional thinking might suggest. While that debate rages, it’s important to note that African Americans are not only safer today than they were 20 years ago (and certainly 50 years ago), they have benefited tremendously from lower crime rates. Over the last 20 years, crime among African-American youth has fallen by 47 percent.

Watching the news can make you feel like we’re on the cusp of falling into a dark time. Maybe we’re destined for a more violent age. Yet it seems the technological and economic advances we’ve made (despite inequality, most Americans live better lives) make it unlikely we’re going to return to 1994- or 1968-style violence any time soon. But who knows? It’s also understandable that emotionally we deal with the incidents that unfold in front of us. Still, it wouldn’t hurt the media to frame the news with a little less scaremongering and a little more context.