Recently I was horrified to find the latest missive from the U.S. Department of Education in my email inbox. It was the Teachers Edition newsletter, which is usually full of teaching tips, like getting kids interested in “The Old Man and the Sea” by having them reenact a crucifixion during Holy Week.

On April 23, 2016, there was no mention of Shakespeare or Ernest Hemingway. The top item was related to Earth Day: new U.S. Education Secretary John King announced Green Ribbon Schools Districts Sustainability Awards and a blog post by a Minnesota elementary school teacher discussed how teachers integrate “an active, outdoor learning component into existing lessons.”

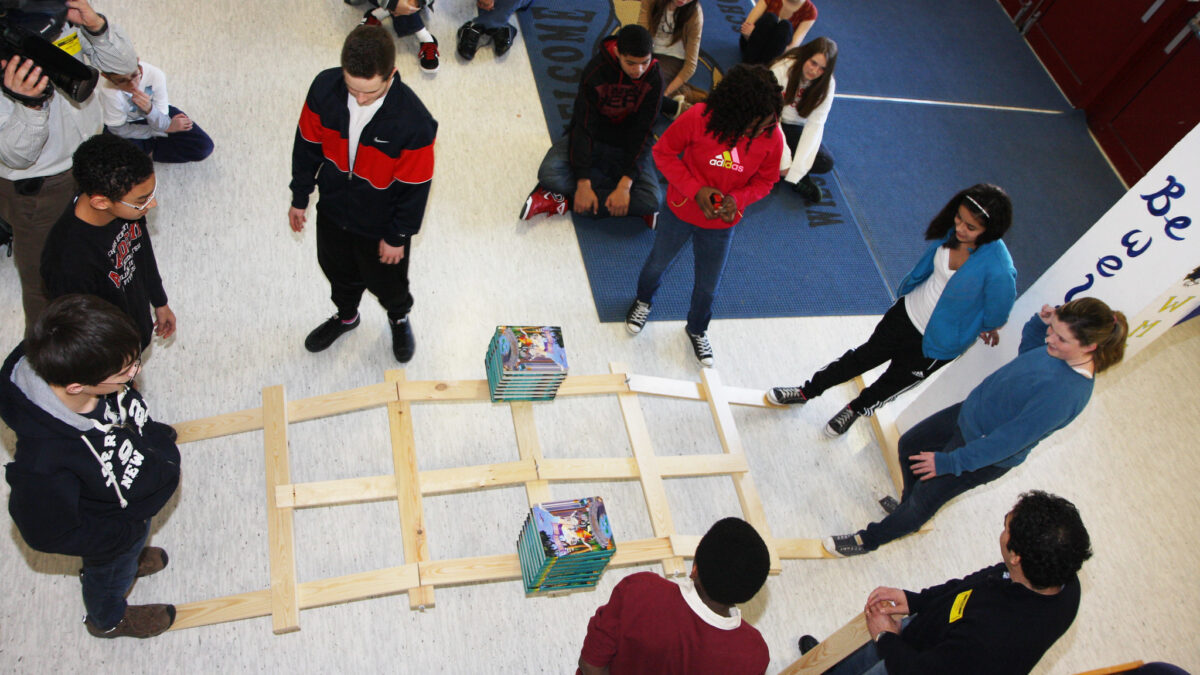

But what really caught my eye was a photo of children lined up on stationary bikes, reading and pedaling away. It accompanied the article “In This Kinesthetic Classroom, Everyone’s Moving All Day.” It was about the “Active Brains” program at the Charles Pinckney Elementary School in Charleston, South Carolina, where “action-based learning” takes place in a classroom equipped with 15 stations featuring such things as mini basketball and stationary bikes, with each focused on different “academic tasks.”

A linked Washington Post article described another classroom, where 28 fifth-graders “sit at specially outfitted kinesthetic desks” or stand at them swaying, or pedal bikes, or march on climbers, while teacher Stacey Shoecraft delivers instruction from a strider at the front of the room. Shoecraft was keynote speaker at the “Kidsfit’s National Charleston Training” and has written a book, “Teaching Through Movement,” on the cover of which a grinning boy jumps into the air and a smiling girl sits on an exercise ball—like one I used when doing physical therapy for my back.

As if all this activity weren’t enough, an article headlined “Libraries Transforming from Quiet Places to Active Spaces” described the American Library Association’s new campaign to transform libraries from “quiet places of research” into “centers of community.” Instagram photos illustrated the concept with “collaborative work spaces, MakerSpaces, [and] bright displays.” The same day the Washington Post had set ten poems to animation in honor of National Poetry Month.

So When Do We Read Books?

As someone who found refuge in the quiet of the library and the order of the classroom as a child, I am disturbed by all this activity. As someone who taught college English for 20 years and saw students’ attention spans decline, I am saddened. My last year of teaching was in 2013, and by then only a couple students would raise their hands when I asked how many had had the experience of getting “lost in a book.” Only a couple had the patience to read carefully the assigned material by Frederick Douglass and Nathaniel Hawthorne.

I’d been observing the transition in teaching styles away from what I knew in the 1960s, when we sat up straight with both feet planted on the floor at desks in rows. Increasingly, news reports show classrooms with kids sprawled on the carpet, reading or writing, or gathered around tables putting objects together, or gabbling like pip-squeak ambassadors about global politics.

Such active learning has been popularized by teacher-celebrities, like Ron Clark, founder of the Ron Clark Academy in Atlanta. At their annual meeting in 2009, I saw social studies teachers applaud him as he jumped onto a chair to describe how his school encouraged “fun!” with a bungee jump and slides instead of staircases (which teachers also use). We were then treated to a demonstration of students’ understanding of civics—through the performance of a rap song about the election.

At the community college where I was then teaching, the annual “faculty development” day featured a session where a popular biology professor rolled her shoulders and stepped side to side to demonstrate how she used dance moves to motivate students. I knew my efforts to adapt this method to discussions about poetic meter or punctuation would get nothing but laughter. It’s not what I signed up for when I earned my PhD and envisioned myself in the female version of the tweed jacket leading thoughtful discussions about John Donne.

At the Core of All This, an Insult to Children

Behind all this emphasis on movement is the effort to close the racial achievement gap, one of the primary objectives of Common Core, evidenced through emphasis on “speaking and listening skills” and “visual literacy.” It’s also evidenced by the U.S. Department of Education’s promotion of educational video games. Such strategies presumably address different learning styles that are said to cause the gap.

This is not a new theory, but one evolved from New Left teachers who founded “urban schools.” By 1988 the theory had gained so much acceptance that the New York State Board of Regents used it in a booklet about high drop-out rates for black students, according to The New York Times. The article explained that proponents argue that “black children require instructions that deal more with people than with symbols or abstractions.”

These educators asserted that black pupils “need more chances for expressive talking rather than writing” and “more freedom to move around the classroom without being rebuked for misbehavior. . . .” Back then the theory was controversial among educators. Today, the U.S. Department of Education promotes this kind of learning for all students.

Thomas Sowell’s recounting of statistics about the superior performance of some black schools against similarly situated white schools during segregation refutes such ultimately racist ideas. He is ignored. That’s because the evidence Sowell presents undermines the stereotypes the Left uses to achieve its ultimate goal: tearing down or significantly altering Western civilization. One way to do that is to change the learning environment from a quiet, contemplative one to a busy, communal one. This assault on “Eurocentrism,” or Western modes of thinking, was deliberate in the 1960s. It is now in the classroom.

Let’s Walk Our Students Like Dogs

Of course, those promoting the new kinesthetic teaching don’t say that. They talk about physical fitness (a problem, to be sure), “motivated” students, and superior test results.

But I wonder: will such strategies backfire? Will making students perform “academic tasks” on treadmills compel them to hate both exercise and learning? I think it might. Such mechanistic exercises, along with Michelle Obama’s “Let’s Move” program, remind me of President Kennedy’s “Physical Fitness in Schools” program and having to run around the perimeter of a scruffy fenced-in yard at Carthage School Number 8 in Rochester, New York.

As a first-grader, I thought it was ridiculous and boring—especially after I’d walked the mile to school and would walk home for lunch and then back, and then home. Of course, children don’t just walk. They run, and skip, and chase each other. Changing into our play clothes when we came home marked the transition to play time, full of tag, hopscotch, dodge ball, jumping rope, and riding bikes, and for the boys, the politically incorrect “cowboys and Indians” and “cops and robbers.”

I thought of this when I saw the picture of students on exercise machines. They reminded me of race horses being cooled down on mechanical walkers. “Academic tasks” sounds like dog training.

The decade of the 1960s brought many upheavals: assassinations, demonstrations, riots. My first-grade class was dismissed early on the day of President Kennedy’s assassination. The riots in adjoining neighborhoods brought over vandalism and violence in ensuing years. Children still played in the streets, though. I would become the exception as I assumed the role of caretaker for my younger sisters. Yet I still had the classroom and library as places of refuge. We were not put on machines; the mandatory runs ended.

I could also walk to the library with my cherished yellow library card. That quiet, mote-filled refuge, long disappeared in urban decay, held rows of books beckoning me to get lost in the wonderful stories. It’s sad that children today are deprived of such simple, quiet pleasures.