This entire post is one long, griping spoiler.

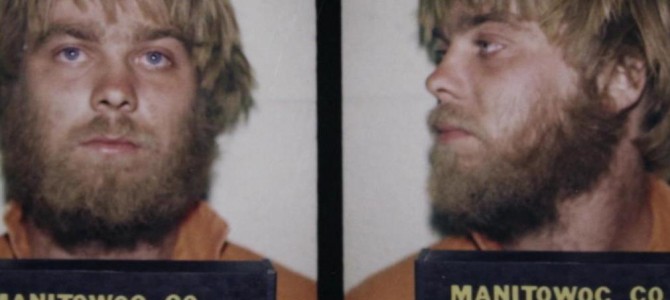

Steven Avery, the subject of the hit Netflix documentary “Making a Murderer,” is currently serving a life sentence for the gruesome killing of 25-year-old photographer Teresa Halbach, whose remains were found in a fire pit on his property in Wisconsin. What makes the documentary so fascinating — and hopefully you’re already aware of this — is that Avery had previously spent 18 years in prison for a crime he didn’t commit. The bulk of the un-narrated documentary focuses on what defense lawyers propose is questionable conduct by police and prosecutors, many of whom, we’re supposed to believe, framed Avery for the crime in an attempt to save their own reputations and the town from fiscal calamity.

I was convinced of many things watching the 10-part series: I was convinced the criminal justice system and Manitowoc County were likely corrupt, and that many people in that office wanted to see Avery end up back in jail. I was convinced that I was being manipulated by directors Laura Ricciardi and Moira Demos (more on this later). I was definitely convinced that Avery was guilty of the murder. And, believe it or not, a viewer could believe all those things simultaneously.

But I feel like I’m in the minority on this. There are now petitions on Change.org and WhiteHouse.gov asking for Obama to pardon Avery (he can’t) that have collected, as of this writing, more than 300,000 signatures. This is utterly absurd.

The DNA evidence exonerating Avery for the rape of a jogger in 1985 did not make him incapable of committing murder (maybe it was his time in prison that transformed Avery into a killer; the documentary doesn’t tell us much about those 18 years in prison, though surely they were traumatic). Yet, it seems that many idealistic viewers want to transfer their anger about the initial miscarriage of justice — and a general distrust of the police — to the new case and use it as reasonable doubt, despite the preponderance of evidence.

Here are some basic things we know right now:

- Parts of Halbach’s body were found burned in Avery’s fire pit.

- Evidence of Avery’s involvement was found inside his home.

- There is DNA evidence tying the bullet found in the Avery garage to Halbach.

- Avery was the last known person to see Halbach alive.

- Police found her car, with blood on it and in it, left on the Avery family’s lot.

- Avery’s high-school age

cousinnephew, Brendan Dassey, confessed that he had assisted his uncle in murder of Halbach.*

Now, to believe Avery is innocent, a person must believe that an implausible number of conspiracies had been unfurled in the case: for starters, the placing of the car, the blood, the body, the keys, and all other evidence. The cover up would have included two DAs and a large group of cops in two police departments. And while it’s not improbable that some of those involved might be morally capable of setting up Avery, Dean Strang (now a sex symbol) and Jerome Buting offered no evidence that anyone had done so, only accusations.

But beyond all that, here are just a few items that the producers of “Making a Murderer” decided to leave out that make the case less riveting and Avery more sympathetic:

— Not only was the bullet found in the garage linked to Halbach’s DNA, but it was forensically tied to Avery’s gun as well. Seems like a pertinent thing for viewers to know. To believe Avery was innocent, you now have to believe that forensics specialists were in on the frame-up and lied about both the DNA and gun, or messed up both tests.

— The criminal complaint claimed that authorities had found restraints — handcuffs and leg irons — at Avery’s residence. In 2006, Avery admitted to buying them so he could use them on his then-girlfriend. This alone doesn’t mean Avery is the killer of course, but it does lend credence to the description offered by Dassey and the police. We heard nothing about this during the show.

— The infamous car key that was found in Avery’s residence had DNA of his sweat on it. So not only are we asked to believe the Manitowoc police department planted the keys in his trailer (and that the neighboring police force was either incompetent or complicit in the deception), but also that somehow the cops had extracted Avery’s perspiration and put it on the key. Another explanation might be that Avery handled the keys when dealing with Halbach, although he denies having ever seen them.

Which bring up additional question: If Avery’s defenders are convinced that DNA from one pubic hair completely exonerates him in the rape case, why does DNA evidence in this case not prove his guilt?

— Avery not only called Auto Trader and specifically requested Halbach to take pictures the day she was killed, but he also gave a false name when he did so. Why? And why would he, and the documentarians, fail to mention it? Avery then called Halbach’s cell phone three times the day she died, twice using *67 to obscure his identity. None of this proves his guilt, but all of these actions undermine the defense’s contention that Halbach was just someone that happened to come by that day for a job. It sounds like he wanted her to come by. None of this is mentioned in the documentary.

— Not only was Avery’s blood — which we’re supposed to believe was planted by the police after being extracted from an evidence room — found in six places on Halbach’s vehicle, but DNA from his sweat was also found on a hood latch. How did it get there? Did the police have a vial of perspiration ready to go the day of the murder?

— You’d also have to be gullible to believe that Avery was merely a flawed, but good-hearted victim of unfortunate circumstance once you learn more about his history. According to an Appleton Post Crescent article from 2006, Avery planned the fantasy torture and killing of a young woman while in prison. According to Ken Kratz at least, Avery also drew up plans for torture chambers while in prison. True? We don’t know. The documentary never mentions (or disproves) any of these accusations.

The young Avery didn’t unintentionally set fire to a cat, as “Making a Murderer” suggests, but poured gasoline on the animal and then threw it into a bonfire, according the Associated Press. And Avery didn’t only threaten a female cousin at gunpoint, an incident the documentary portrays as the unfortunate actions of an immature teen, but is also alleged to have raped a young girl and threatened to kill her family if they spoke out, according another story in Post Crescent (paywalled). If we’re to believe Dassey’s conversations with police, Avery had also molested his cousins. “I even told them about Steven touching me,” Dassey explains to his mother after one of the interviews with police.

Now, we don’t know if all or any of these accusations are true. But we do know that the documentary didn’t offer viewers the full picture of Avery’s purported behavior and ugly proclivities. Yet, the same filmmakers had no problem bringing up Kratz’s sexting scandal and other unpleasant tidbits about the prosecution and police, though they had nothing to do with the case itself.

Why would Avery leave the keys in his room? Why would he leave the vehicle in his lot? Who would be that stupid? He had to be set up. I hear this defense often. Well, maybe Avery is not very bright. Maybe Avery didn’t have time to rid himself of the evidence. Who cares? Whether he was smart enough to mastermind a murder or whether he once faced an injustice of the system, doesn’t change the facts of this case. Maybe if I was on the jury I would see things differently. My judgement is made solely on the evidence available to me as a viewer. Maybe we’ll hear new evidence moving forward that changes all of this, but “Making a Murderer,” much like “Serial” before it, is a work of advocacy journalism.

I’m not sure there is anything wrong with advocacy, as this is still a compelling look at the families of the victims and suspects and their experience in the American justice system, but we shouldn’t pretend that it’s something else.

*For me the matter of Dassey’s confession was the most problematic part of the case. The police interviews with him were almost unwatchable at times. The detectives’ questioning of Dassey (and describing what they did as “questioning” is far too charitable) without an attorney or family member present, despite the kid’s obviously low IQ, was abuse. Kratz’s press conference misrepresenting the tenor and outcome of that confession was nothing more than a lie. Yet, it needs to be pointed out that Dassey’s confession was far more specific than his other stories and comported with evidence that turned up.